Robert Kennedy Brought Hope to Detroit Only Days Before His Death

Robert Kennedy died 50 years ago, only two weeks after campaigning in Detroit. He brought together segments of the electorate who seldom seem to unify now. And some of those with him in Detroit wonder if anyone can ever bring those factions together again.

A half-century ago Robert F. Kennedy was assassinated in Los Angeles.

Kennedy’s death came only a few weeks after he had campaigned for the presidency in Detroit.

And Kennedy left an impression, and a void, that some in Metro Detroit say lingers to this day.

Cheers Amid the Ruins

At a Detroit park on the corner of what was once 12th Street and Clairmount, a photographer glances at the site that sparked three days of violence in 1967.

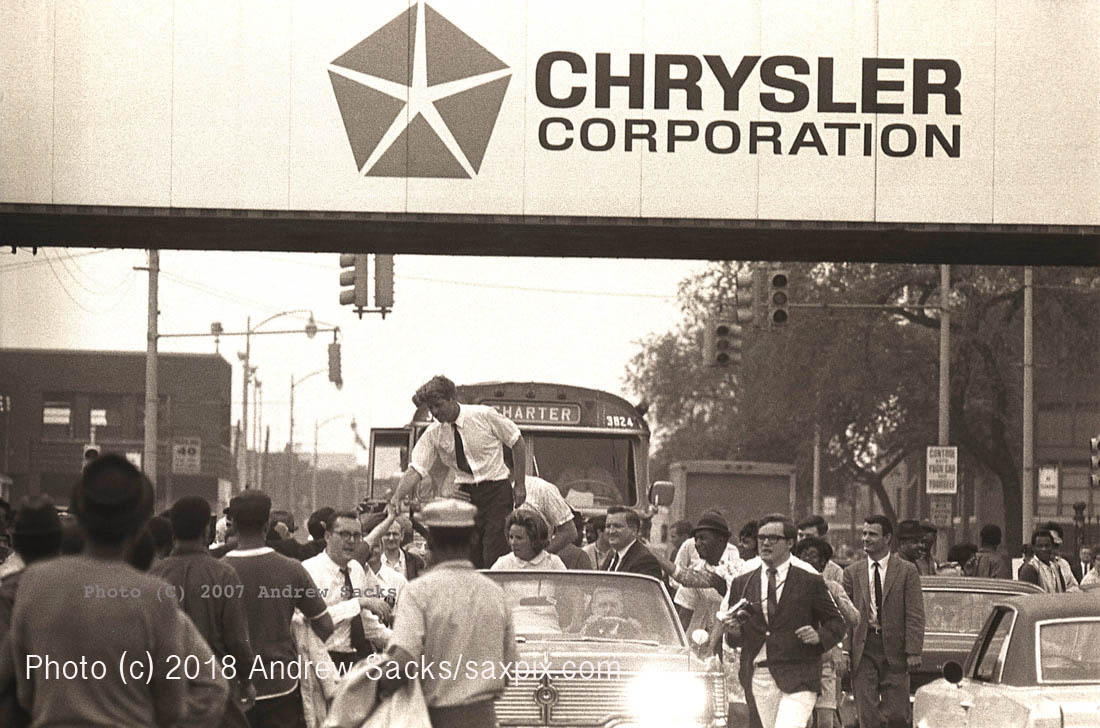

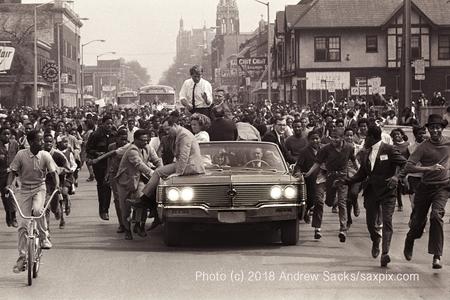

Back then Andy Sacks was a young journalist for the Michigan Daily student newspaper, one of several who crammed into Robert Kennedy’s motorcade as he campaigned in Detroit in the spring of 1968.

Sacks says after a few stops the motorcade purposely targeted this intersection, an area many at the time said should be avoided because it was seen as one of the most dangerous in Detroit.

“Sure he was a rich guy from Boston. But he seemed to have a vision of government and the way it should interact with the whole of the population of the United States. He connected with inner city people.” – photographer Andy Sacks

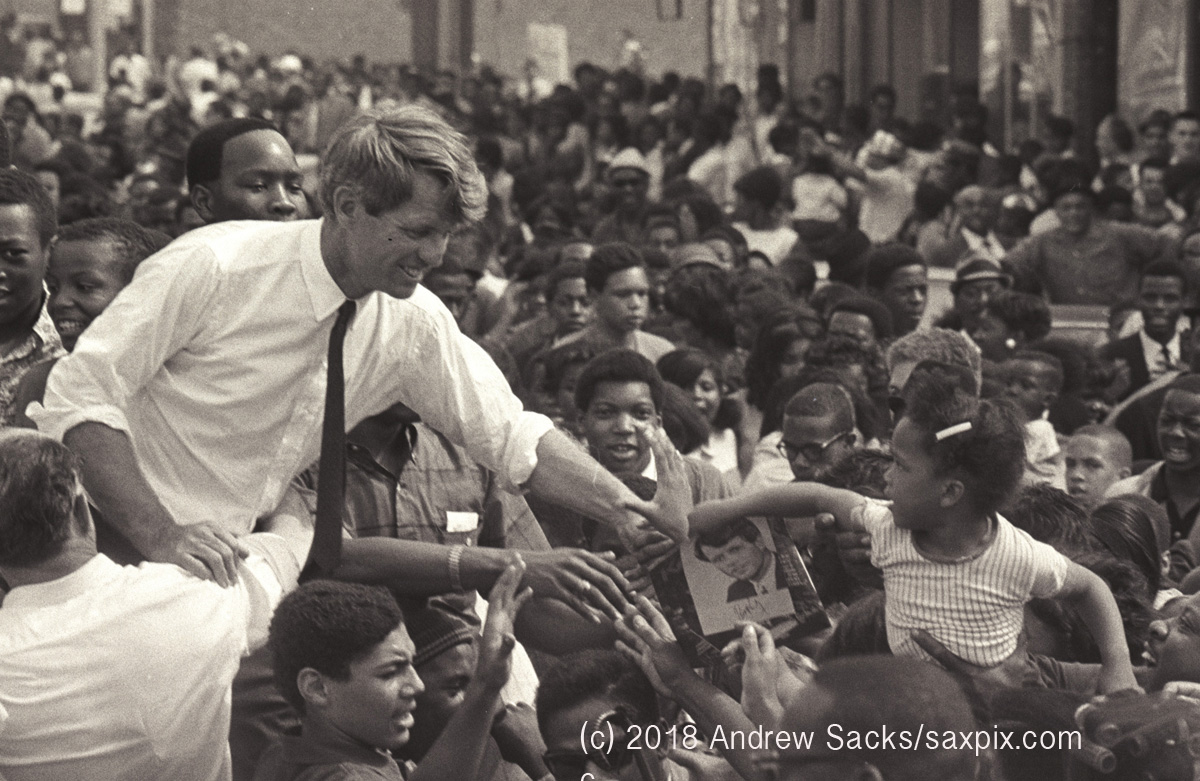

Kennedy, however, perched atop an open convertible and was quickly surrounded by an adoring crowd.

“As a photographer I could get pretty close to him,” Sacks remembers. “When he reached down to shake someone’s hand they really gave it a big tug. And I saw him start to lose his balance and begin to fall into the crowd. I just put down my camera and reached out with one of my hands and pulled him back up. He had no bulletproof vest, none of that protection. But he did have someone of his campaign crew holding him around the waist so he wouldn’t be pulled out of the car.”

Sacks calls it a surreal sight.

He says the vestiges of violence were still visible in a neighborhood filled with happy people cheering one of the most famous politicians in the country.

“I’m just amazed at how many people were on the street and the kind of celebratory atmosphere. Sure he was a rich guy from Boston. But he seemed to have a vision of government and the way it should interact with the whole of the population of the United States. He connected with inner city people,” Sacks says.

Trailed by Threats

After President John F. Kennedy’s assassination in 1963, brother Bobby became a champion of the civil rights movement.

And Robert Kennedy constantly challenged those who denied basic human liberties after he became a U.S. senator.

A 1966 exchange during a senate sub-committee hearing with a California sheriff who was arresting migrant workers was typical of Kennedy’s approach at the time.

He asked the sheriff, “Who told you (the workers) were gonna riot?”

The Kern County Sheriff responded, “The men right out in the field that they were talking to. They said if you don’t get ‘em out of here we’re gonna cut their hearts out. So rather than let ‘em get cut, you remove the cause.”

Kennedy seemed flabbergasted. “How can you go arrest somebody if they haven’t violated the law?”

The response? “They’re ready to violate the law.”

Kennedy shook his head. “Could I suggest…that the sheriff and the district attorney read the Constitution of the United States?”

Such comments led to threats of violence against the brother of the slain president.

And another young photographer in that 1968 Motor City motorcade., .Jay Cassidy, says those threats followed Robert Kennedy to Detroit.

“The first stop on the trip was Cadillac Square, the downtown square,” Cassidy says. “And there was a huge crowd there and he gave basically a campaign speech. And then he went into a hotel and came out and that’s where the group (was) called Breakthrough, which was sort of a hate group that had also protested against Martin Luther King earlier in March. They arrived sort of in a group with signs (reading) ‘Give us your blood Bob. All of it.’ “

Members of the group had also trailed Kennedy to Detroit the year before, when he gave a speech during the Jefferson Jackson Democratic Party event at Cobo Hall.

Their message had not changed in the intervening years.

“Mr. Kennedy…offered to donate blood to the Viet Cong,” one unidentified protester told television reporters at the time. “So we consider that a man in the position he’s in, a senator of the United States, that says that he wants to donate blood to the enemies of this country and the murderers of his brother, then we think he should donate all of it…There’s people willing to take that blood and send it to the Viet Cong. All of his blood.”

The threat was not very veiled. And it was not beyond the bounds of possibility in a decade that had already seen Kennedy’s brother, the President of the United States no less, gunned down.

Though he was about a year away from declaring his own bid for the presidency, Robert Kennedy had already honed the message he delivered to Detroit Democrats that day. The U.S., he said, could not be judged a strong nation simply because it was the wealthiest country on Earth.

“For the Gross National Product includes air pollution and advertising for cigarettes and ambulances to clear our highways of carnage. It counts special locks for our doors and jails for the people who break them. The Gross National Product swells with equipment for police to put down the riots in our cities. And though it is not diminished by the damage those riots do, still it goes up as the slums are rebuilt on the ashes,” Kennedy said.

A year later photographer Jay Cassidy says he was taken aback by how then-presidential candidate Robert Kennedy seemed determined to get close to the crowds he drew in 1968 Detroit, whatever the cost might ultimately be.

“And there weren’t that many cops around either. He was incredibly vulnerable against the sea of people. He wanted to be there and he wanted to make that contact. So he put himself in that position,” Cassidy says.

The Only One Who Could Calm Them

By 1968, Kennedy’s mere presence was something of a tonic at times.

He calmed a mostly African American crowd in Indianapolis the night Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was murdered, then intended to put his campaign on hold until after the funeral.

“When you teach that those who differ from you threaten your freedom or your job…then you also learn to confront others, not as fellow citizens, but as enemies. But…they share with us the same short moment of life. They seek, as do we, nothing but the chance to live out their lives in purpose and in happiness.” – Robert F. Kennedy

But civil rights activists pleaded with Kennedy to keep an appearance scheduled for the next day before business leaders in Cleveland.

They wanted him to present the kind of message of non-violence he had in Indianapolis, as other cities across the country burned in the wake of King’s death.

Kennedy responded with a speech that was in many ways an indictment of American society.

“There is another kind of violence, slower but just as deadly destructive as the shot or the bomb in the night,” Kennedy said. “This is the violence that afflicts the poor, that poisons relations between men because their skin has different colors. This is the slow destruction of a child by hunger and schools without books and homes without heat in the winter. This is the breaking of a man’s spirit by denying him the chance to stand as a man and as a father. And this too afflicts us all.”

Kennedy had rarely publicly addressed the death of his brother John.

But on this day after King was killed, Kennedy’s words defined what he called the “mindless menace of violence.”

In measured tones Kennedy told the business crowd, “When you teach that those who differ from you threaten your freedom or your job or your home or your family, then you also learn to confront others, not as fellow citizens, but as enemies. But we can perhaps remember that those who live with us are our brothers. That they share with us the same short moment of life, that they seek, as do we, nothing but the chance to live out their lives in purpose and in happiness. Surely this bond of common fate can begin to teach us something.”

A Promise Awaiting Fulfillment

Those words still resonate back at the site of the start of the 1967 Detroit rebellion.

Photographer Andy Sacks sits there, staring five decades into the past. He was barely in his 20’s then.

But by early June of 1968 Sacks had already seen the assassination of a president and a civil rights icon.

Then came the news of an assassin’s bullet fired at Robert Kennedy in California.

And Sacks says he feared he’d finally seen the death of a dream.

“I heard that Robert Kennedy had been killed,” Sacks says. “I just sort of said ‘Hmm, okay, this is America isn’t it? It was sad. I still get kind of emotional about it. Because we looked at him as a hope for the country. And that hope was gone after he walked into that hotel kitchen in Los Angeles.”

Sacks says he wonders if there will ever be another politician with Robert Kennedy’s ability to inspire people to, in the words of Abraham Lincoln, seek “the better angels of our nature.”

Robert Kennedy, by all accounts, was not a saint.

But he called for unifying all segments of the U.S. populace, with a campaign, a well-known personal story and a searing vision that made that promise seem within the nation’s grasp.

There appear to be few ready to shoulder that mantle in these bitterly-divided political times.