Detroit Exits Most State Oversight

After three years of balanced Detroit budgets, the Financial Review Commission votes to suspend oversight.

Five years ago, Detroit became the biggest municipality in U.S. history to file for bankruptcy, but now state oversight of the city’s finances has ended.

Officially it happened with a unanimous vote of the Financial Review Commission (FRC), the 11-member panel that was formed as part of the grand bargain legislation.

But what led to that vote was three consecutive years of balanced budgets, and a host of new financial management controls, processes and people.

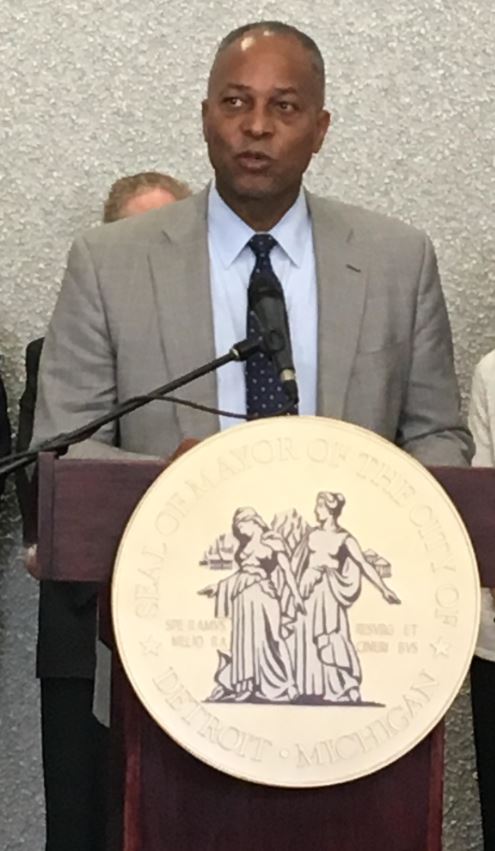

“This is a day we all had hoped would come,” said Detroit Chief Financial Officer John Hill. “Nobody knew it would come this quickly.”

Not everyone agrees with the city officials’ assessment of success. Several community advocates attended the FRC’s last meeting Monday. A few spoke during public comments. A few heckled during a state official’s remarks.

“We live in the neighborhoods and we are not getting what we deserve,” said Helen Moore, a member of Keep the Vote/No Takeover and the National Action Network, who spoke during the commission’s public comment period. “I’m happy to be here for this occasion, and I’m going to say something that probably suits me very well: good riddance.”

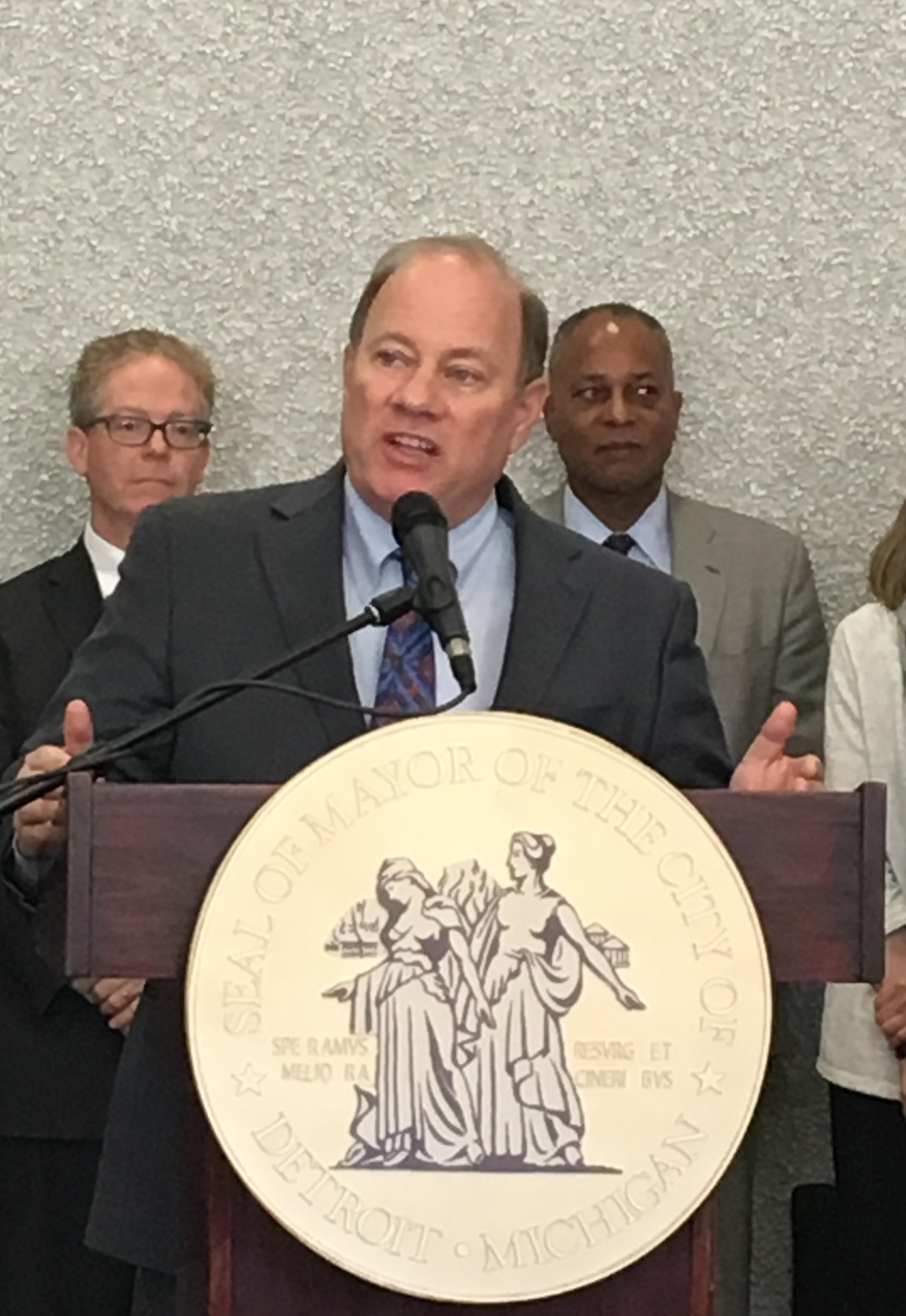

Still, most of the day involved city and state officials lauding the city’s financial comeback with a focus on the balance sheet, which Mayor Mike Duggan says is reliable.

“You remember five years ago when you got monthly financial reports, they weren’t much more than guesses. We were trying to figure out roughly how much cash was in and out the door,” the mayor said.

New financial reporting systems changed that, and Hill credited several other moves for the city’s financial position. First, the ccity shed billions of dollars in debt during the case, including retiree health care and some pension obligations. Then the city leveraged exit financing that’s paid for improved city services.

Detroit also managed credit upgrades that helped lower interest rates and borrowing costs when the city refinanced some bonds.

On the revenue side, the city has increased its collection of both property and income taxes, and casino tax revenues are steady.

But Hill said serious challenges loom: the pensions for some 30,000 people. While the bankruptcy cut pensions, moved new workers into 401k-style plans, and postponed some payments, the city must start making them again in about five years. The amounts are sizable portions of the city’s overall budget.

But Hill says the city is preparing but earmarking current budget surpluses and working future payments into budgets.

“Obviously the city did not put its head in the sand that we had a substantially larger amount of money that we would have to come up with for our pension plan,” he said.

But Moore says the bankruptcy did not provide justice for residents of the city who still have insufficient services, high poverty rates and no equitable development in the neighborhoods. She criticizes what she sees as the city’s focus on downtown business and entertainment districts.

She had clear instructions for the state oversight commission and city leaders.

“Look around you,” she said to the commission. “I want you to see the real people that live here and are suffering under what’s going on. We don’t live downtown. We live in the neighborhoods and we are not getting what we deserve.”

The city will continue to submit monthly reports to the Financial Review Commission and the City Council, Hill said.