Summer of Love Preceeded 1967’s Civil Unrest in Detroit

Detroit hippies flocked to Belle Isle on April 30, 1967.

Editor’s note: This story was written and produced by Noah Ovshinsky in 2007 as part of WDET’s reporting on the 40th anniversary of the city’s civil unrest.

In many ways, Detroit’s civil unrest defined the summer of 1967. But before the first rock was thrown, before the first store was looted, there was another kind of rebellion brewing that summer — a cultural one.

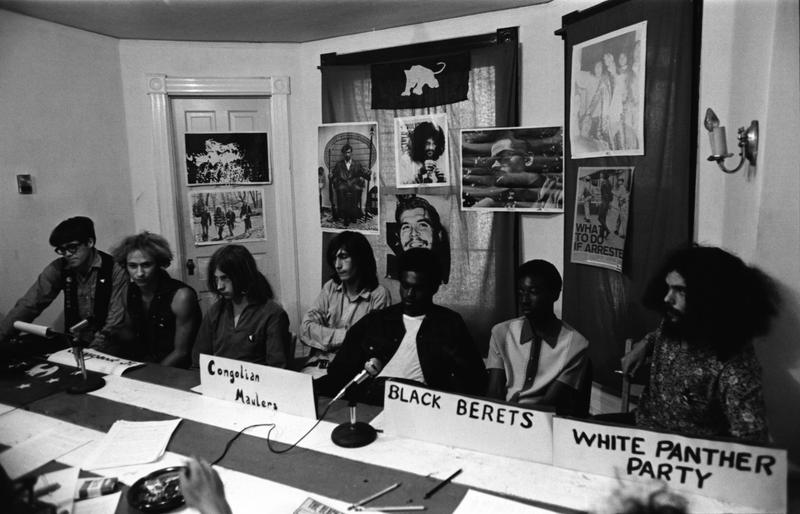

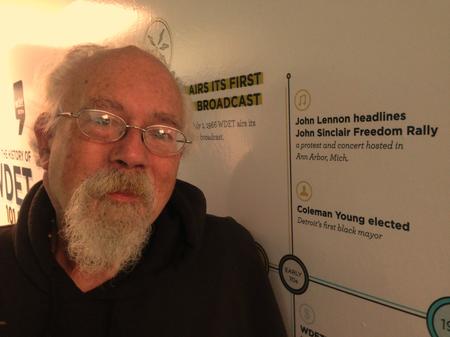

In January 1967, several months after Timothy Leary urged the youth of America to “turn on, tune in, and drop out,” thousands of young people were flocking to the San Francisco area — particularly the Haight-Ashbury district — to partake in free food, free drugs, and free love. The popular press called them “hippies”, but at its roots, the growing underground movement embraced the avant-garde, the musicians and poets who were breaking the rules. Eventually the movement came to Detroit. No one was more instrumental to that move than John Sinclair. He was a member of the Detroit Artists Workshop — a group of writers, musicians, and artists who lived near the Wayne State University campus. Gary Grimshaw was a young artist at the time. His psychedelic posters would later come to define Detroit’s counterculture. He joined the workshop in March 1967.

“It was a very complex thing that covered every aspect of living, and it’s hard for me to cook it down into a few sentences. It was a way of life that was new to us.” — Gary Grimshaw

As much as the movement was about drugs, sex, and rock ‘n roll, it was also about change. In 1965, John Sinclair married Leni Arndt, who took her husband’s surname. Leni Sinclair says the counterculture emerging in Detroit and elsewhere was a rebellion against the status quo.

“There was just something in the air that wanted change real bad,” Leni Sinclair recalls. “And everything was part of it. Just young guys letting their hair grow and defying authority in that way, and going to concerts with like-minded people to the Grande Ballroom. You know, those people who wanted to drop out of their society and start something new.”

If one place were to become synonymous with the hippies, it was the Grande Ballroom, a concert hall on Detroit’s west side. At the time, it featured some of the biggest names in music. Its owner was Russ Gibb. He says there was a profound sense among the hippies of not wanting to live the lives their parents led.

“The hippies of their day were people who were saying ‘we’re not satisfied about the way we’re living’,” Gibb says. “We don’t want to live in a tract house in a suburb. We think there’s some value in living in the city. We think there’s some value in sharing and not just gaining for yourself.”

The music heard at the Grande was also starting to reflect the changing attitudes. A group of young musicians formed the band MC5. The group took its industrial roots and produced a sound that was hard-edged and high energy. Michael Davis was the band’s bassist.

“We felt it was, like, our duty to inform people that they were kind of, like, languishing in the past, and we had a new doorway for them to step into the future, into something that was much more exciting and much more truthful than anything that had happened before” — Michael Davis, MC5 bassist

[Ed: Michael Davis died in 2012, five years after this report originally aired on WDET.]

The leaders of the Artist’s Workshop — and later Trans-Love Energies — looked west toward the blossoming underground. John Sinclair and others didn’t want to have to leave Detroit to be among like-minded people. Leni Sinclair says they wanted to bring the Haight-Ashbury to Detroit.

“Our whole idea was ‘No, we don’t want to leave. We want to make it like they are here, and then nobody has to leave. This will be the center where everything is happening,’ And to a large extent it was, you know?” — Leni Sinclair

To bring a little bit of San Francisco to Detroit, John Sinclair conceived an event modeled after the Human Be-In held in Golden Gate Park . Sinclair wanted to hold a day-long event that would include free food, free drugs, free love, and free music. He wanted to have it on Belle Isle. So, he and other members of Trans-Love Energies started planning. They got the proper permits, designed the posters, and booked the musical acts. On April 30th, 1967, thousands of people streamed onto the island. Most were from the suburbs, curious about the counterculture. But others were already immersed in it. MC5 Bassist Michael Davis.

“And then you had this kind of, like, a minority of people that were already into it,” Michael Davis recalled. “They were already there, they were stoned, they had the fringes on, they had the hair was long, they had everything was going.”

Also on the island that day were dozens of Detroit Police officers, including many on horseback. Gary Grimshaw says as far as the police were concerned, the hippies were trouble.

“Well, because we smoked weed and hung out with black people, and we attracted suburban kids to come down and do the same. And they didn’t like that,” Grimshaw says.

For most of the day, the event remained peaceful. But at 7 p.m., the situation changed. The MC5 were on stage. Michael Davis explains what happened next.

“We started our ‘Black to Comm’, thing and wouldn’t you know it, ‘Black to Comm’ just, like, took the cap off the thing. And I mean, we always felt like we caused it, you know, that the chaos and the high energy of ‘Black to Comm’ just sent people, just turned it into a disaster.”

The police arrested a motorcyclist for reckless driving. A confrontation ensued with the audience before things got violent. Thousands fled the island. On the other end of MacArthur Bridge, police were again confronted by an angry mob. Glass was broken, and more than a dozen people were arrested. The day after the Detroit Love-In, Leni Sinclair — nine months pregnant at the time — started worrying about a backlash. She thought the police would blame Trans-Love Energies and hippies for the violence.

“We were scared,” Sinclair says.”We thought we may have to flee or something, I don’t know. With the foreboding aftermath, I remember we were huddling and just really being sad and disappointed and scared.”

Leni Sinclair says regardless of the Love-In’s violent outcome, change was in the air. She says things had to get better. In the following months, John Sinclair and Trans-Love Energies would continue their quest to legalize marijuana. Resistance to the war in Vietnam would continue to grow across the country. In Detroit, United Auto Workers President Walter Reuther would admit to working with the CIA, and Circuit Court Judge George Bowles would continue his campaign to root out corruption in Wayne County.

Four days after the love-in, Leni Sinclair gave birth. Almost three months later, the Detroit Police would raid a blind pig near the intersection of 12th Street and Clairmount . Another rebellion against the status quo was set to begin.

(This story was originally broadcast in 2007)..