How the U.S. Constitution Does and Does Not Protect Your Privacy

Legal scholars and privacy experts weigh in on the privacy protections granted to all Americans through constitutional provisions and federal statutes.

As part of 101.9 WDET’s Book Club, we’re inviting the Detroit region to examine and discuss the text that impacts every resident of the United States: The Constitution. Whether you’re revisiting the documents or reading them for the first time, join us in reading along and engaging in civil conversations with your community.

There is a wide expectation that the government cannot intrude into our private lives. But the word “privacy” never actually appears in the U.S. Constitution, raising the questions of where does that expectation come from and how equality fits into that notion.

As WDET examines various provisions of the Constitution this summer, that idea of whether there is fairness in the distribution of these rights is a key piece in looking at the Constitution through the lens of equity. When it comes to privacy, is that right respected equally for all Americans? And how have civil rights and other issues having to do with equality fit into existing protections around privacy? In this age of big tech, big data and the proliferation of social media, looking at our right to privacy has never been more urgent.

“Although the word ‘privacy’ is not [in the Constitution], the concept and protections are there. The founders valued privacy in terms of private property and that value is very much present on the surface of the Constitution.” –Anita Allen, University of Pennsylvania

Listen: Experts weigh in on how and why technology is straining privacy protections for the American public.

Guests

Anita Allen is the University of Pennsylvania Carey School of Law’s Henry R. Silverman Professor of Law and Professor of Philosophy. “Although the word ‘privacy’ is not [in the Constitution], the concept and protections are there. The founders valued privacy in terms of private property and that value is very much present on the surface of the Constitution,” notes Allen. She explains that there is a political undercurrent in the public’s discussion about how the Constitution doesn’t contain the word “privacy.”

Allen explains that the politically charged nature of privacy rights can be traced back to the 1960s when several progressive social movements took shape guided by privacy rights. “In the 1960s we got birth control and abortion rights based on a right to privacy and we saw the Fourth Amendment privacy doctrine around the same time,” she says.

Allen also points out the noteworthy NAACP v. Alabama Supreme Court case in 1958, which was groundbreaking in setting legal precedent regarding an associational right to privacy. “It flipped Americans’ notions of privacy,” explains Allen. “Privacy had an unequal role in 19th century, but in the 20th century, wise and insightful African Americans and their allies were able to use the right to privacy to benefit their rights,” she says.

Florian Schaub is an Assistant Professor of Information at the University of Michigan’s School of Information. His research focuses on empowering users to effectively manage their privacy in complex socio-technological systems. “We see this creeping erosion around what protections around privacy there are,” says Schaub, discussing the role of technology in privacy issues today. “Technology is straining the legal protections we have particularly around privacy,” he says.

On the ubiquity of surveillance and tracking by way of technology, Schaub notes that it is insidiously and inextricably a part of our culture, whether we are aware of it. “If you scan a QR code everywhere you go, you realize you are tracking into a business but in reality we are all carrying a tracking device in our pockets … in the form of our smartphones. This tracking is happening regardless of whether you realize it,” says Schaub. He notes this mass surveillance is especially striking in the ways it impacts marginalized communities.

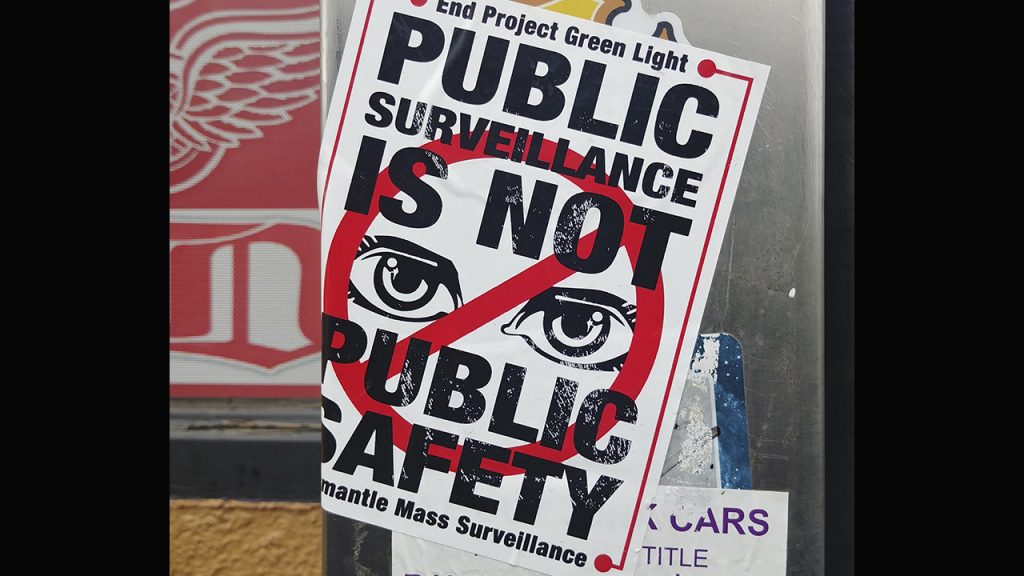

Tawana Petty is a Non-Resident Fellow at the Digital Civil Society Lab, lifelong Detroiter and National Organizing Director at Data For Black Lives. She has worked extensively to bring awareness to the privacy implications of Project Green Light. On the ways the program has affected her, Petty says it’s about the ways it creates anxiety in day-to-day life. “You are living under a perpetual lineup and with the companion facial recognition technology, you are just hoping you don’t get picked up for something you didn’t do,” she says.

Petty also notes that “there’s this conflation between surveillance and safety … the quality of life in Detroit has eroded. So we have quality of life crimes and we don’t have the investment in resources … instead we have officials reacting with surveillance programs,” says Petty.

Join WDET in reading the Constitution.

This summer, we invite you to get involved as we explore our nation’s founding document.

Sign up to get your free pocket Constitution

Trusted, accurate, up-to-date.

WDET strives to make our journalism accessible to everyone. As a public media institution, we maintain our journalistic integrity through independent support from readers like you. If you value WDET as your source of news, music and conversation, please make a gift today.