The Art of Community: How the City, Citizens, Donors Created the Detroit Institute of Arts [VIDEOS]

New book chronicles role of philanthropy and finance in DIA’s history and future as a public institution.

The Detroit Institute of Arts originally was built with money allocated by the city and contributed from its residents. That relationship between the museum and its donors is the focus of a new book called “Valuing Detroit’s Art Museum: A History of Fiscal Abandonment and Rescue.”

Its author, Jeffrey Abt, a professor of art history at Wayne State University, spoke with WDET’s Sandra Svoboda about how the DIA’s history reflects the city’s, especially when it comes to finances and the bankruptcy.

Click on the audio link above to hear Abt’s full conversation with Sandra.

Here’s a transcript of what they discussed:

Svoboda: Why write a book now about the financial history of the Detroit Institute of Arts?

Abt: I was prompted to write it because of the news coverage about the museum and the bankruptcy and the misunderstandings, in some ways, the surprise that a lot of people had over the fact that the city could sell part of the collection possibly to settle their debts. And I could tell by the news coverage and also by the questions that journalists were asking about the museum’s history and how that could come about, and

I thought it was important to relate the history of the museum and its collections, its very tangled relationship with the city of Detroit, to the bankruptcy, the notion that the art might be sold.

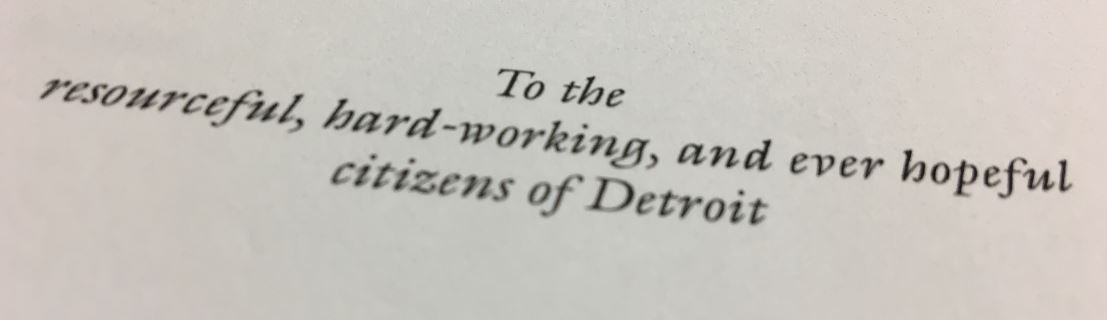

SS: You dedicate the book to the “resourceful, hard-working and ever hopeful citizens of Detroit.” What does that dedication say to how you wrote the book in terms of including residents’ and citizens’ perspectives throughout the history of the museum?

JA: The museum was built with money from Detroit’s citizens, and

I think that many of the patrons of the museum who donated art to the museum over the years really donated it because they viewed the museum as a public institution and they felt that they were building something that was going to endure, that was going to belong to the citizens of Detroit for generations to come.

So I think it was that sense of the optimism with which the museum was created and the betrayal that was implicit in the idea of the bankruptcy and the sale of the collection that I thought was important to address.

SS: What were some of the story lines that you saw in the media that you took objection to?

JA: One was the idea that the collection could be sold and that people were surprised by that. And that, I think, represented a real misunderstanding in the sense that, “Oh, those Detroiters, they don’t appreciate art. They’d be willing to sell the collection.” It bothered me because in truth, even though the Detroit Institute of Arts at that time belonged to the city of Detroit, other art museums around the country could just as easily, if they got in pinch, sell collections.

They couldn’t be forced to sell collections by the city but if the trustees of the museum screwed up and needed to sell works of art to balance their debts they could and there would be nothing to stop them.

SS: Why should people read your book, “Valuing Detroit’s Art Museum: A History of Fiscal Abandonment and Rescue”? What can readers get out of it?

JA: I wrote it primarily for people who are interested in public policy, interested in the role of museums in American society, and in particular some of the issues that affect museums today and will affect museums in the future that I think museum professionals and people who care about museums need to think deeply about.

One of them is this question of the notion of the public trust.

It’s not enough for a museum to say it exist in the public trust or it serves the public trust. It really needs to characterize itself legally as a charitable trust otherwise its collections will always be in danger if its trustees screw up, which happens all too often in America. And I think the other is to be wary of the pressures of the art market on museums and to understand the very complex but pressing ways that this international, I would say, sort of global art investment community is affecting the funding for museum, museums’ ability to not only acquire works of art but also to tour works of art and certainly if they’re beginning to have financial problems to feel that well, in fact the works of art in a collection are a commodity and they can be exchanged when there’s trouble