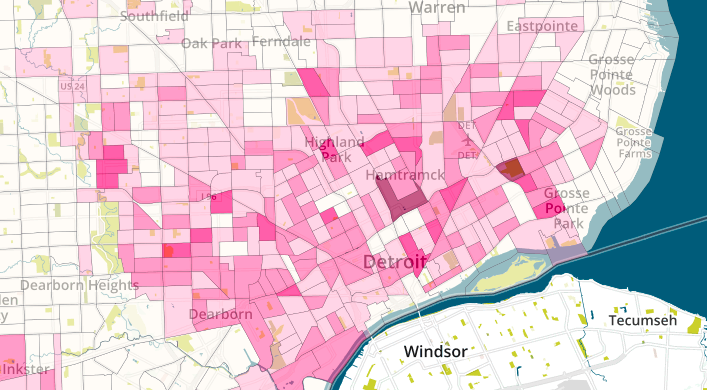

Where is Poverty in Metro Detroit? [Map]

We mapped poverty in metro Detroit and talked with Metro Matters’ Conan Smith to understand why and where it occurs.

You may see it everywhere, or you may never see it at all, depending on where you live. As the map below shows, metro Detroit’s poverty is concentrated in certain areas.

Poverty in Metro Detroit [MAP]

Data source: American Community Survey 2009-2013 (provided with the assistance of Data Driven Detroit). Data are mapped by census tract.

When poverty is concentrated in a few places in a region, it creates special challenges and conditions. Conan Smith, director of Metro Matters, a regional research and advocacy nonprofit, talks with WDET’s Sandra Svoboda about these dynamics and proposes some ways poverty could be reduced.

Poverty and income challenges for households: give me the “elevator speech” on the issue.

As we look around the region, we see growing disparities between the rich houses and the poor houses. And more importantly, we’re starting to see concentration of poverty and concentration of wealth, and the subsequent inability of communities to dig out of consequences of that. The city of Detroit is a great example. Left with a concentration of poverty, they didn’t have enough resources to tackle some of the standard service delivery challenges, and that’s reflected in communities all across this region.

Is it at all possible to say what percentage of a city’s municipal budget goes toward services for low-income populations?

It’s really tough to parse out, but I think it’s a little easier at the county level than it is at the municipal level, because counties are tasked with more of the social services. So I think you could generally say at the county level, easily 30 to 40 percent of their entire budgets are being focused on issues and programming that support the poor and the very poor. Within the municipal government context, it’s a considerably lower percentage; more of their services are general. For example, if you are rich or poor, you deserve to have excellent police service and excellent fire service, right?

Talk specifically about what’s in a county budget that goes to those low-income populations?

At the county level, you have responsibility for most of the mental health services, most of the food services for the poor, pretty much anything that’s a community-oriented service has some connection to the county, especially if it’s public health, mental health or community-development oriented. So affordable housing, for example, is generally in the bailiwick of the county, and so are the community action agencies so the work with the very poor to build up their communities to make them stronger and more stable.

What differences are there between higher-income communities and low-income communities?

The tragedy here is that from a human standpoint there shouldn’t be any, right? But in a high-income community, what you see are people putting the equivalent percentage of their income into running their government, but getting a much better, bigger, higher degree of service out of that. So for example, if I earn $30,000 a year and you earn $100,000 a year, we’re each putting 5 percent of our income into that to provide services for our community, you’re going to get more just because you’re putting more in, and that gets reflected across the region in terms of police service and fire service, garbage pick up, the quality of community planning that you’re able to do, your school districts, everything. So as we concentrate poverty and concentrate wealth into individual autonomous communities, we see really big disparities in service delivery.

Talk a little bit about the characteristics of southeast Michigan in terms of those concentrated areas of low-income earners.

The big outlier, of course, are neighborhoods within the city of Detroit. Places where you’re seeing perhaps 80 percent of the population living at or below the poverty level. That’s at the neighborhood level. Across whole cities, we see everything from places like Birmingham, that really don’t struggle with a poverty challenge hardly at all, to places like Lincoln Park and River Rouge, where unemployment is high and household incomes are critically low.

So it runs the gamut, and our big challenge is that various social forces are compelling people to live in neighborhoods with people of like income. And so whole communities develop that don’t have diversity in their income structure, and we get places where the poor and the very poor are concentrated, and trying to deliver services, whereas you have other neighborhoods or other communities, or whole cities sometimes where people are pretty rich.

I think one of the interesting places to look at actually is the city of Ann Arbor, though. We often think of Ann Arbor as being an affluent community full of lots and lots of rich people. It has 22 percent of its population are at or below the poverty level. It has a real income diversity. What you see in communities that do have that income diversity is an ability, a capability to deliver quality services across the spectrum. That really should be the goal for all of our region.

I think in our region it is easy to conflate race and income. So race and class get blended together and not wrongly so because of a whole lot of reasons. If you’re black in our community, the likelihood is that you’re going to be poor. So there is a high correlation between race and poverty, but what is challenging is that in most people’s minds, the two become the same. And so we often think about transit, for example, as being a service for the poor or for African Americans. We conflate the two in our mind, and the service become racialized itself. Both of these things have to be talked about, in my mind, simultaneously, if we’re actually going to able to address them.

Take me through issues that become bigger for low-income households or communities with a high portion of low-income households.

Just your basic safety and quality of life concerns. If you think from the municipal standpoint, municipalities should provide some very basic services: public safety, public health. When you live in a community that doesn’t have the capacity to deliver consistent, regular police protection, it makes it easier for crime to evolve and the nature of a community to tolerate crime, therefore, changes. Similarly with public health. If you don’t have regular garbage collection, people will find ways to take care of their refuse. They’re not going to live with it, but that often becomes then a public problem rather than a problem that the public services has resolved.

So it’s more like a magnification of the natural tendencies of everyone. Nobody wants to live with garbage in their backyard, so we have developed garbage collection services, right? But if we can’t afford garbage collection services, what are you going to do with it? You’re going to find some other way to handle that mess.

To me, those are the real big challenges from a quality-of-life standpoint. But then on top of it, you start to see that people don’t get access to all sorts of other critical services. So for example, access to hospital care and clinical care. We have great non-profits that are putting clinics in low-income communities, but if you live in a high-income community, you have easy access to those things.

Part of providing easy access to that is our transportation system. So if I make $100,000 a year, I’m going to own a car and I’m going to be able to get to all that stuff in this region. If I’m earning $20,000, or $15,000 or $10,000 a year, I’m going to be public transit-dependent, and our transit system struggles to get all of those people to all of those places across the metropolitan region, so often you go without just because it’s not possible to get to places.

Assuming we think poverty and income levels in the region are a problem, how do we fix it?

The solutions have to be done on regional scale or larger. I’d start really at the top, at the state level. We have got to have a progressive income tax. There are 23 states in the nation that already have this, where if you make more money you pay a higher percent of your income into the supporting the social fabric of your community.

In Michigan, we have a flat income tax, and so for those people on the lower-income scale, they’re putting a higher percent of their non-discretional spending into taxes. Those on the higher-income scale can bear that burden a lot easier. So we really need, at the state level, to be thinking about progressive income tax.

As you work it down to the regional scale, there are strategies like the collective tax action of collecting taxes and redistributing them across the region. Places like Minneapolis in the Twin Cities area have being doing this for 20 years. New Jersey has a progressive tax collection and redistribution program so that those communities with lower tax bases are receiving a higher share of the regionally generated revenue, so that they have the capacity to deliver some of these critical services. Then of course there are the private sector components of this as well. People need to be earning a living wage. We need to make sure that the businesses in our community have the capacity and also feel the moral responsibility to provide that kind of an income steadily.

Mapping by NIna Ignaczak.

Powered by The Detroit Journalism Cooperative with support from The James L. Knight Foundation, The Ford Foundation, and Renaissance Journalism’s Michigan Reporting Initiative.