A Grieving Mother Seeks Answers After Detroit Police Investigation of Daughter’s Shooting Death

Kaniesha Coleman died of a gunshot wound in July 2020. A medical examiner called it a homicide shortly after that. Eight months later, at the urging of Detroit homicide investigators, her death was reclassified as a suicide.

The morning of July 16, 2020, Antoinette Ivery got the worst news of her life. Her daughter, Kaniesha Coleman, was in the hospital.

“I was told that she had shot herself,” Ivery says. “Reason and understanding just went out the window.”

Ivery rushed to her daughter’s bedside, but Kaniesha was getting worse. Two days later, the 25-year-old mother of two died from a gunshot wound to the abdomen.

Ivery says her daughter’s death was hard enough to process. But then, she started hearing a second story of what happened.

“I had talked to doctors, nurses and the 8th Precinct. They told me that from the wound and from the scene, it did not look like she had shot herself,” Ivery says.

Like many cities in the U.S, Detroit has seen a surge of gun violence since the onset of the pandemic.

Most of the crimes go unsolved.

According to the FBI, the Detroit Police Department reported 328 murders in 2020. They cleared 139 of them. Aggravated assault has a lower arrest rate. There were more than 11,600 offenses reported and police cleared just over a third of them. DPD reported 1,173 non-fatal shooting victims in 2020, a 53% increase from the previous year.

For Ivery, the police investigation that followed her daughter’s shooting felt like an attempt to bring one less number to those statistics.

Despite Documents to the Contrary, Police Pursue Suicide Narrative

According to hospital records, Kaniesha Coleman was conscious when EMS brought her into the emergency department at Sinai-Grace Hospital. She told doctors she heard a gun go off and realized she had been shot.

Detectives had more detail. In their report, Coleman stated she was the victim of an aggravated assault at the home where she stayed with some relatives. On July 19, a Wayne County Medical Examiner declared her death a homicide.

“There was no soot or gunpowder stippling noted on the skin anywhere on the abdomen,” assistant medical examiner Jeffrey Hudson wrote in his postmortem report.

But in the weeks that followed, Ivery says DPD was eager to reclassify the cause of her daughter’s death. In texts and emails, homicide investigators began to frame the case as a suicide, with little proof and some glaring omissions.

“I started hearing about different evidence they didn’t have like a gun,” Ivery says. “If you didn’t find a gun you know it’s not a suicide. She couldn’t have shot herself and hid her own evidence.”

No arrests were made at the scene of the incident and any account of the weapon that was used in the shooting was missing from the police’s investigation report.

“Initial impressions is that it is all nonsense and it does not make sense whatsoever. Everything has to be proven somehow.” — L.J. Dragovic, Oakland County Chief Medical Examiner

Ivery was frustrated with the state of the investigation and took her grievances up the police chain of command. She contacted the head of DPD’s homicide unit, Captain Derrick Maye, and his superior, then-police chief James Craig.

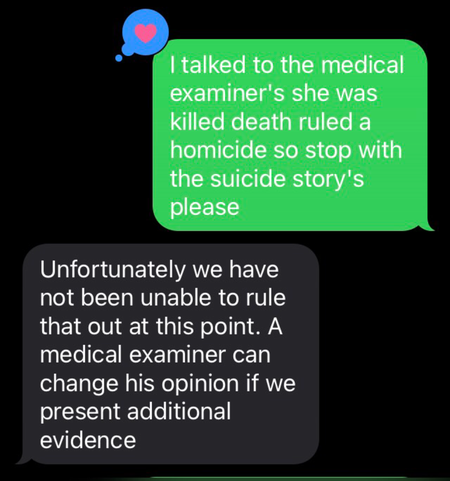

“I talked to the medical examiner’s she was killed death ruled a homicide so stop with the suicide story’s please,” Ivery wrote to Maye over text a few months after her daughter’s death.

“Unfortunately we have not been unable [sic] to rule that out at this point,” Maye texted in response. “A medical examiner can change his opinion if we present additional evidence.”

After initial conversations, her texts and calls would eventually go unreturned. Investigators updated her less and less frequently. Ivery says the experience made her feel ignored and distrustful of the police department.

“It’s left me feeling like basically, they’re God and I’m nobody,” Ivery says, holding back tears. “I’m Black. I’m a low-income mother. I’m not a famous person. I don’t have a lot of money.”

“I felt like, they felt like they could railroad me and tell me anything because I have no way to fight back.”

After Citizen’s Complaint, a New Postmortem Report

In November 2020, four months into the ongoing investigation, Ivery escalated matters. She filed a citizen’s complaint with DPD’s Internal Affairs and the Board of Police Commissioners — the two bodies responsible for police oversight in Detroit. She brought up the fact that police had not found a firearm at the scene and waited to see what the oversight officials turned up.

She’d find out the following year, confirming the worst of her suspicions.

In February 2021, more than eight months after Kaniesha Coleman died, the Wayne County Medical Examiner’s Office reclassified her death as a suicide.

In its new report, the examiner referred to the work of DPD’s homicide unit, which spoke with witnesses to the incident. They claimed Coleman’s gunshot wound was self-inflicted. Police used lie-detector tests during their interviews, the results of which would not be admissible in Michigan courts. But citing that testimony, police concluded the people with Kaniesha that July morning were not lying, leading the examiner to overturn the initial ruling of homicide. No new physical evidence was entered by the examiner.

Kaniesha Coleman’s murder investigation was over because technically, no crime had been committed.

A Second Opinion

The Detroit Police Department declined to be interviewed for this story as did Michigan Medicine, where Hudson is employed. The University of Michigan has a five-year deal to operate the Wayne County Medical Examiner’s Office until October 2022. The contract costs more than $31 million.

“In some cases, it can be unclear whether a wound was self-inflicted and medical examiners depend on police investigation to assist in determining cause of death. Coleman also had previous surgery, which further changed the appearance of the wound. The medical examiner’s report was amended in February when the police investigation concluded it was not homicide,” Michigan Medicine spokesperson Mary Masson wrote in a statement.

Other experts have spoken with Ivery about her daughter’s death.

L.J. Dragovic is the Medical Examiner for Oakland County. He says he hasn’t seen the photos related to the case. But the reports he has seen raise some serious questions.

“Initial impressions is that it is all nonsense and it does not make sense whatsoever,” says Dragovic. “Everything has to be proven somehow.”

Dragovic says medical examiners use a variety of physical evidence to determine how someone died, like finding gunpowder residue on the body. The first report noted that was something not present anywhere on Kaniesha Coleman.

“It’s left me feeling like basically, they’re God and I’m nobody. I’m Black. I’m a low-income mother. I’m not a famous person. I don’t have a lot of money.” –Antoinette Ivery, mother of Kaniesha Coleman, who was killed in a shooting

Dragovic says changing someone’s cause of death is rare — and something he’s never done in his more than 35-year career. The fact that the second report cited a polygraph test to change a homicide to a suicide, he says, is even more concerning.

“That is not tangible evidence,” Dragovic says. “If those are used to persuade a person responsible for medical, legal death investigations to change something, it’s got to be something much more than that.”

Detroit’s police oversight panel did not find any fault with the case despite that perspective. A month after the homicide unit closed its investigation, Ivery was informed that her citizen’s complaint had been administratively closed. When she got a copy of her complaint, she was upset by the number of errors it contained. The officer who prepared the report spelled Kaniesha’s name with a “J” and the date of the shooting was incorrect.

Those that investigated the complaint note that that Ivery’s report was taken by a member of DPD Internal Affairs. Still, the Office of the Chief Investigator, which examines matters for Detroit’s Board of Police Commissioners, stands by its conclusions.

“The complaint that she made with our office is she felt that the Detroit Police Department was not doing any work on her case, period,” says interim chief investigator Lawrence Akbar. “My investigators went out and did their fact-finding and found that in fact, the homicide section was doing an investigation with respect to the death of her daughter.”

According to preliminary data from the Board of Police Commissioners, the 8th precinct, which covers the area where Kaniesha Coleman died, led the police department in citizen complaints in 2020. Most were procedure-related.

Read the Board of Police Commissioners preliminary report >>

There were more than 3,800 complaints against DPD that year. Most ended with no charges against the officers in question, or the BOPC determined the complaints themselves were unfounded.

Many were administratively closed, just like Ivery’s was.

Others Weigh In

More than a year after her daughter died, Antoinette Ivery is considering her legal options as she seeks answers to the police investigation. Ivery hired a private investigator, hoping they can deliver better answers after the public ones let her down. Attorneys in the area say there is a pattern of conduct by law enforcement in the city.

“I believe there’s reason to be concerned about the ways in which the Detroit Police Department has historically investigated serious crimes,” says Julie Hurwitz, a civil rights attorney and a former vice president of the National Lawyers Guild.

“There is a built-in incentive within the Detroit Police Department to rush to judgment and to try to solve the crime quickly rather than correctly and so they can get credit for solving the crime.”

The pressure to quickly close police investigations has been observed by those with experience overturning wrongful criminal convictions.

“The problem is that you are so consumed with how many times the door knocks with another case and you don’t have the staff, you don’t have the money, you don’t have the experience, you don’t have the expertise. You don’t have the help to get them done the way they should. It is almost a human trait to start to cut corners to make sure you keep your job,” says Bill Proctor, a former broadcast journalist and police officer who now leads Seeking Justice, which advocates for the wrongfully incarcerated.

“The ripple effect continues and is impossible to reverse or compensate for.” –Bill Proctor, Seeking Justice

“It’s these kinds of things that maybe drive the misconduct that we find because it’s egregious. It is known to the individuals who are part of the structure of a wrongful conviction.”

Proctor says supervisory powers within government like the chief law enforcement officer can scrutinize cases and potential wrongdoing. Members of the Wayne County Prosecutor’s Office have been in touch with Ivery about her daughter’s case. A spokesperson denied further involvement, saying police investigators did not send over a warrant request as the case was ruled a suicide.

Alleged criminal behavior by Detroit police officers has come to the forefront this year as part of an ongoing federal corruption probe. During “Operation Northern Hook,” federal prosecutors charged five city officials with bribery, including a former supervisor in command of the department’s Integrity Unit, which is responsible for investigating potential misconduct of officers.

Separately, DPD’s Internal Affairs concluded a two-year corruption probe into the department’s narcotics unit, resulting in the departure of a dozen police officers. As the result of “Operation Clean Sweep,” investigators concluded the group lied about informants, planted evidence and falsified search warrant affidavits. Criminal charges are still pending.

Proctor says bad police work can upend the lives of those subjected to mistreatment and their kin.

“The ripple effect continues and is impossible to reverse or compensate for.”

Ivery moved out of Detroit over concerns about her safety and is taking care of her daughter’s kids. One is 9 years old now, the other is 5. She says her family never got the grief and loss counseling that comes through DPD’s Victim’s Assistance Program.

“You’re basically a nobody to them,” Ivery says.

“Had I been a rich person or a famous person, or even my daughter had been somebody, I felt like they would have treated us different. But because they look at her as a nobody and I feel like they look at me as a nobody, they didn’t see reason to take the case serious in the first place.”

Listen: Her daughter’s death was hard enough to process. Then Antoinette Ivery started hearing a second story of what happened.

Trusted, accurate, up-to-date.

WDET strives to make our journalism accessible to everyone. As a public media institution, we maintain our journalistic integrity through independent support from readers like you. If you value WDET as your source of news, music and conversation, please make a gift today.