From homicide to suicide, families sue Wayne County morgue over ‘outlandish’ record revisions in gun-related deaths

The families of two shooting victims in Detroit have filed $1 million civil rights claims against the Wayne County Medical Examiner’s Office.

Two families are suing the Wayne County Medical Examiner’s Office over a pattern of behavior concerning “bizarre, unwarranted and unreasonable” death record revisions, embroiling half of the facility’s working coroners in a civil rights dispute.

In both cases, homicide declarations for individuals who died by gunfire were overturned and reclassified as suicides following Detroit Police Department homicide investigations. Parents of the deceased, both young Black adults, contend death investigators with DPD and Wayne County coroners failed to properly notify them of the revisions to the death records, discovering additional autopsy reports through their own persistence.

Listen: Families sue Wayne County morgue over record revisions in gun-related deaths

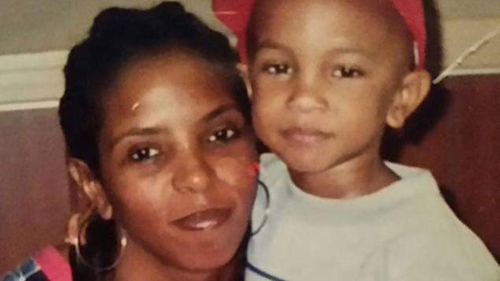

“They never notified us,” says Melanie White, whose son, Isaiah White, died of a shotgun blast to the back of his head in September 2021. The 22-year-old Chicago native’s death was reclassified as a suicide several weeks after an initial homicide declaration, a discovery his mother made only after filing a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request.

“There’s a cover-up with my son’s homicide,” White declares.

WDET reviewed police documents, body-worn camera footage, and post-mortem reports from Isaiah White’s investigation, finding officers’ first impressions of the shooting differ from written reports from the scene. A Wayne County medical examiner initially declared that White “could not have shot himself.”

The lawsuits follow WDET’s investigation of Kaniesha Coleman and the changes to her death record. Once deemed a homicide, Coleman’s shooting death in July 2020 was reclassified as a suicide eight months after an initial report. The change was prompted by Detroit homicide detectives — who presented no new physical evidence to the medical examiner — relying solely on witness interviews and polygraph tests to amend the case as a suicide.

Read: Grieving mother seeks answers after Detroit Police investigation of daughter’s shooting death

A Wayne County medical examiner initially declared that White “could not have shot himself.”

In the months since the story’s publishing, Coleman’s mother, Antoinette Ivery, has sought resolution through the courts. Both Ivery and White have filed $1 million civil rights claims against the Wayne County Medical Examiner’s Office, alleging the death record changes were made because of the “perceived disposability” of their children’s race.

Despite her convictions in the case, Ivery worries that the wide-ranging partnerships among public institutions and government offices will prevent an outcome in her favor.

“I don’t see it going good,” Ivery tells WDET. “They have the city, the county and the judges in their back pockets. That’s the reason they’re comfortable doing what they’re doing.”

Michigan Medicine, which ran the Wayne County morgue during White and Coleman’s death examinations, did not respond to a request for comment due to the pending litigation. Current administrators told WDET they have committed to improving operations at the facility after an audit revealed widespread mismanagement.

“This sequence of events is something that needs explanation,” says Dr. Wael Sakr, dean of the Wayne State University School of Medicine. WSU started managing the Wayne County morgue in October 2022 under a five-year, $72 million contract.

However, current officials have been unable to account for other death record revisions or their frequency in the county, denying several of WDET’s FOIA requests for more information.

“He was loved. He was Ikey.”

There’s a deep well of sadness that Melanie White draws from when she talks about her son.

“He was my heart, my only child,” White says. “And now my light has just disappeared.”

Isaiah White was a Chicago native with family ties in Detroit. His father, Darren Pollard, describes him as a quiet and introspective young man.

“I saw a lot of myself in him, good and the bad,” Pollard says. “Every day feels like it happened yesterday.”

That day was September 21, 2021, when early that morning, White was found dead in his house by Detroit police. As described by investigators, his death was caused by a “contact shotgun wound to the back of his head.”

When family arrived at the scene, there were various accounts of what happened. White’s roommates claimed he had shot himself. He did have a history of mental illness and self-harming.

However, White’s parents were told by law enforcement officials that wasn’t the case.

“The police called me, and they said, ‘We have reason to believe that it wasn’t a suicide,'” Pollard recalls.

The reports were further confirmed in writing.

“I received the death certificate the weekend of his service,” White says. “When I opened up the envelope and saw ‘homicide,’ I just lost it.”

The two had lingering questions as new details came to light. White did not leave a note and the weapon found at the scene wasn’t his. It was a compact shotgun owned by his roommate, a firearm with a nearly 19-inch barrel. It seemed impossible to his parents that their son could have shot himself as described.

After the funeral, Pollard went to speak with the homicide detective investigating his son’s death. Even though his family was learning new details, he was told investigators were reversing course and looking into the death as suicide. The father protested the new direction of the case.

“I started telling him all the things that I had learned, and he got really dismissive,” says Pollard. “I left a little bit frustrated, and from that point forward, he didn’t return my calls.”

White’s parents made several unsuccessful attempts to contact Detroit Police in the following months. Emails went ignored and the two live out of state, making contact even harder.

“There’s a cover-up with my son’s homicide.” – Melanie White

Melanie White took matters into her own hands. She filed a series of FOIA requests, spending hundreds of dollars on police records and post-mortem reports. All of White’s attempts to learn the truth about her son’s death led her to one conclusion.

“It’s a cover-up. That’s it. Nothing else. There’s a cover-up with my son’s homicide.”

“It doesn’t look like a suicide.”

It was just after 1 a.m. on September 21, 2021, when Trey Lapsley, Isaiah White’s cousin and roommate, called 911.

“My cousin just shot himself,” Lapsley is heard telling the operator in audio taken from the 911 call obtained by WDET.

Lapsley explains he was playing a video game in his room when he heard the shooting. After seeing White slumped over on a couch, he says he immediately left the house.

“Are you willing to go see if he’s still alive and breathing to see if we can control the bleeding on him,” the operator asks.

“I don’t think I can do that,” Lapsley responds.

Police arrive within minutes. When they reached the scene, Lapsley was outside with his brother and their mother. According to police reports, the family was contacted before the 911 call was placed. They told officers again that White had shot himself and had a history of mental health issues.

But as body cam footage, photographs and official reports show, police observed something different when they entered the house that caused them to doubt Lapsley’s story.

“This is not a suicidal thing,” says Corey Davis, one of the first Detroit police officers to examine White’s body.

Police make several remarks during their investigation that the scene was “odd” and that the shooting was “an iffy call to make.”

“I feel like it doesn’t look like a suicide,” one officer says. “A suicide you’re by yourself [and] you’re not doing anything.”

“[He’s] chilling with a cigar,” another officer replies.

Officers find White lying on the couch, dead from a single gunshot wound. On the floor to his right, there’s a shotgun surrounded by several shells. His left hand has blood on it, and his right is holding a blunt as if he’s just been smoking. By all accounts, White was right-handed.

“I don’t think you can hold [the shotgun] that way,” says Davis.

Regardless of their first impressions, officers say it’s not their job to decide what happened. They call in Detroit police’s Homicide Unit before the video ends.

There’s no mention of debate in written police records. In registering his body, an investigator reports that the police’s initial survey of the scene was that White had died by suicide.

Two days later, Deputy Chief Medical Examiner Leigh Hlavaty performed an autopsy and shared her opinion.

“Investigation revealed that [White] could not have shot himself in the back of the head with the shotgun in question and only using his left hand,” Hlavaty concluded.

“Thus, the manner of death is homicide.”

White’s family says they only found out about the details in the coroner’s report after their FOIA request. It’s also how they discovered a second report that officially changed their son’s death from a homicide to a suicide.

“Further investigation by police revealed that this wound was self-inflicted,” Hlavaty reported in November 2021, nearly two months after the shooting. She recounted details officers were told when they first arrived at the scene about White’s suicidal ideation and his roommate’s accounting of the events. The second report also mentioned a blood pattern analysis, which led Hlavaty to amend his death as a suicide.

White’s family has yet to see the blood analysis used to change his death record. That document was not provided through the family’s FOIA requests.

Detroit Police did not further elaborate on the case and did not make itself available to review the investigation. DPD did report that shootings have been up since 2019. Of the 327 gun-related deaths in Detroit in 2021, police report 45, including Isaiah White’s, were by suicide. Representatives for the Lapsley family who were at the house that night did not return a request for comment.

Lawyers for White and Coleman’s families contend that a discriminatory pattern of conduct at play allows for revising deaths based on superficial information.

“These are both African Americans, and they were both lower-social economic,” says attorney Dionne Webster-Cox. “We need you to do your job and investigate.”

Out-of-state medical examiners who reviewed the case say it’s possible that White could have killed himself as described. But many shared concerns that the coroner’s initial report was premature and a revision should have been made with better communication with White’s family.

“They should have waited and gotten more information,” says Cyril Wecht, a forensic pathologist overseeing several high-profile investigations. “They had no basis to just move ahead and call it a homicide initially.”

According to the Wayne County Medical Examiner’s Office policies, coroners are “ultimately responsible” for contacting next-of-kin about deaths. But that kind of contact was just one of the many failings at the morgue.

Problems at the Wayne County morgue

Ivery and White’s litigation follows an audit that uncovered several operational issues at the Wayne County Medical Examiner’s Office. The building itself was in a state of “major disrepair” according to reports. The document cited poor building maintenance that left pipes freezing, causing a power outage in 2021 that stopped a cooler from working and causing bodies to rapidly decompose.

The audit noted there wasn’t enough staff, and most of the pathologists working at the morgue were not board-certified death investigators. There were significant issues in tracking bodies and major delays in their release. Thousands of families were potentially not informed about deaths transported to the morgue. Because of those failings, the National Association of Medical Examiners gave Wayne County only partial accreditation.

The audit findings prompted an administrative shift at the Wayne County Medical Examiner’s Office. Dr. Carl Schmidt, who led the organization for nearly three decades, was replaced last summer.

The University of Michigan Health System had administered aspects of the county morgue since 2011, offering a one-year forensic pathology fellowship program. In 2022, Michigan Medicine’s five-year deal to operate the medical examiner’s office for $31 million was not renewed. As stated earlier in this story, Wayne State University assumed management of the organization on a five-year, $72 million contract last October.

“We walked into a situation that’s sub-optimal,” said Sakr. “But I think we have a very concrete plan, and we have been delivering on it month after month in getting to what we need to be.”

While Wayne State makes its changes, there are some holdovers from the previous administration. Dr. Lokman Sung is the interim chief medical examiner and has worked at the morgue since 2007. He says many of his colleagues from Michigan Medicine stuck around during the transition, though the morgue is only half-staffed, with about four full-time pathologists working as of February.

“We are battling a decrease in physician numbers but also an increase in case numbers,” says Sung.

Wayne County has examined more than 3,500 bodies yearly since 2020, making it the busiest morgue in the state. Sung reveals half of those cases are not given an official death declaration, like a homicide or suicide classification. They’re put in a pending status, usually reserved for drug-related deaths as they await toxicology reports.

Death record revisions can also happen for other reasons.

“It is very rare that does happen,” says Sung. “When we issue the manner of death, it is based on the information that we have presently. If in the future additional information comes, we will evaluate that information and determine if we must amend the original manner of death.”

It’s unclear how often those kinds of changes happen. Officials with the morgue say the data is recorded in computer code that current staff cannot access. A request to get the information from the Michigan Vital Records office was also rejected.

In reviewing White’s documents, Sakr, himself a pathologist, noted the death record change happened through an addendum report, even though the revision was more significant.

“Addendum, in general, means you’re adding information, and you’re not contradicting anything before,” Sakr explains.

When White’s record change was sent to the state, it appeared as a supplemental report to a pending death certificate, a form used to make changes on undetermined cases. The document is dated February 16, 2022, nearly five months after his death. According to state health code, a revision that far removed would typically require a court order.

The February date is significant for another reason — it was the same day White’s family got their FOIA response from Wayne County for his death records.

Sung could not account for the discrepancy in the county’s communication to the state or why someone in his office would have changed White’s death from a homicide to a suicide. But he does acknowledge a medical examiner’s opinion can influence police work.

“If you put ‘pending’ on the death certificate, I’m not saying no investigation would have been performed, but I think the level of scrutiny when addressing a pending versus a homicide, there’s going to be more on the homicide case,” states Sung.

Attempts to contact Hlavaty went unanswered, but she has offered some insight about what it would take to cover up a murder.

Hlavaty and her colleagues recorded more than two dozen episodes of Detroit’s Daily Docket, an official podcast for the Wayne County Medical Examiner’s Office, where they discussed topics that arise from their work and the true-crime genre.

“Staging a death requires a lot of planning, intimate knowledge of policies and procedures of local law enforcement and the local medical examiner or coroner’s office, and some level of cooperation from the victim,” Hlavaty explains in one episode. “A contact gunshot wound fired by oneself or another would look the same, but the devil is in the scene details.”

Isaiah White’s family has been immersed in the details of his shooting for months. For them, the lack of concrete answers they’ve received from investigators has made them confident of one thing — officials have moved on from a tragedy that White’s family is still seeking answers for.

“Everything in my life has turned upside down, and I can’t even get the courtesy of a civil conversation,” Pollard says. “I think that’s just some bulls–t.”

Melanie White agrees.

“To me, it’s just another Black kid dead in the street and you don’t care.”