Michigan’s Recovery Mobile Clinic makes health care more accessible

Nurse practitioner Jordana Latozas started the mobile clinic to help treat addiction in underserved communities. Now, it also combats COVID.

The Recovery Mobile Clinic helps reach vulnerable populations, especially those who are dealing with alcohol or substance abuse.

Jordana Latozas is an acute care nurse practitioner. While working at a brick-and-mortar clinic, she noticed many patients had a hard time finding transportation to their appointments. So, she founded the Recovery Mobile Clinic in Michigan in February 2020 as a way to bring care to them.

“My husband happens to sell RVs. We put our heads together a little bit and started investigating the mobile model and how it can apply to addiction medicine, and really found that there isn’t a whole lot out there. So we formed the nonprofit and got it going on the road.”

Latozas says she soon realized being flexible and meeting people where they were helped reach vulnerable populations — especially for people who were dealing with alcohol or substance abuse.

“Pre-pandemic, we were treating — I would say about 70% of our population was opioid, heroin, fentanyl addiction and about 30% was alcohol. Post-pandemic, those numbers have flipped.”

She says the pandemic increased stress, isolation and lack of support for people who may have already been struggling.

Along with alcohol or substance abuse, the Recovering Mobile Clinic also sees patients for general care.

“We do see a lot of homeless, we see a lot of people in transitional housing, women’s shelters, that kind of stuff. We’re really trying to reach the population that is hard-hit. Addiction transcends socio-economic barriers.”

Providing an alternative solution

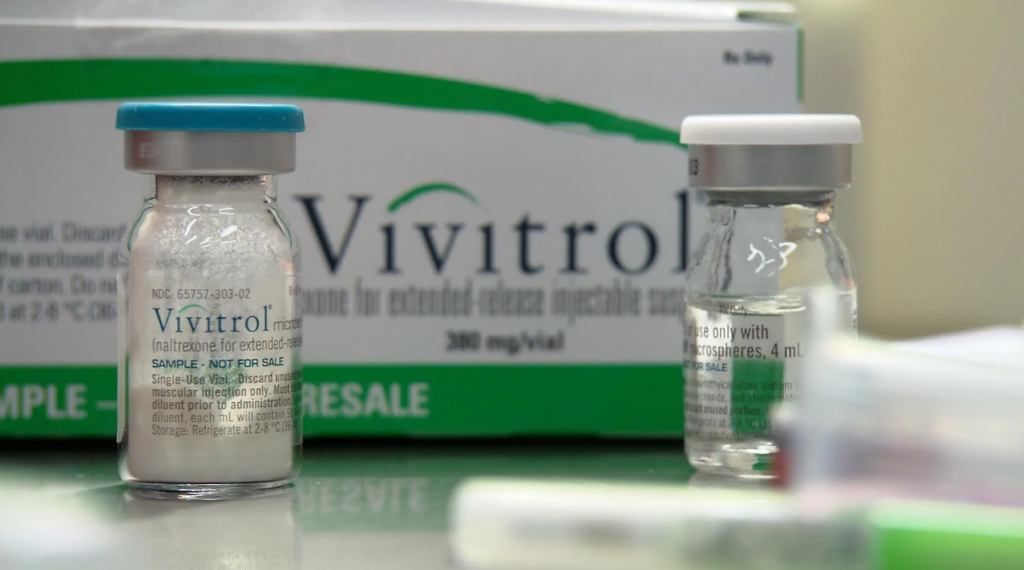

Latozas says the mobile clinic provided about 400 Vivitrol injections or “400 months of sobriety” to the community. The medication blocks cravings for alcohol, and “blocks the signals going in or out of opioid receptors in the brain.”

That means the medicine helps people lose the craving for alcohol or opioid long-term. But that requires people to get off alcohol or opioids for about 14 days prior to taking the medication in order to avoid major withdrawal symptoms.

“That’s that can be a hard number for a lot of people to reach, especially when they’re going through that withdrawal transition. People who go through an inpatient program or a transitional house have a better success rate of maintaining that full 14 days, but we can push it to seven.”

The clinic takes insurance and provides free care for those uninsured through donations.

“We also formulated the nonprofit side of it, which is called the Patient Recovery Fund… It’s almost like our own insurance company. So 100% of donations go directly towards patient care. What will happen is a patient comes into the clinic that does not have insurance, we see them, we treat them exactly the same.”

Beyond health care

Latozas says the mobile clinic provides case management.

“We’re also going to work with them on, ‘Let’s submit the Medicaid application. Let’s get the paperwork going. Let’s put them in a better situation.'”

She says these things can seem intimidating for those overcoming addiction.

During the pandemic, the mobile clinic served those in need, like people who were removed from homeless shelters during winter months. Latozas says the mobile clinic provided COVID tests or vaccines — expanding to seven counties in the process.

“When COVID hit, what we were able to figure out really quickly is that municipalities’ fears came down significantly if you could meet them at where they needed you the most. We had COVID tests, COVID vaccines, things that we could bring into the community.”

She says it’s important to make a difference.

“Nurses do the best when we are with patients one-on-one… When you build that relationship on a community basis with somebody… that’s what keeps me going.”

Listen: How a Michigan mobile clinic is fighting for wellness in underserved communities.

All photos courtesy of Recovery Mobile Clinic.

Trusted, accurate, up-to-date.

WDET strives to make our journalism accessible to everyone. As a public media institution, we maintain our journalistic integrity through independent support from readers like you. If you value WDET as your source of news, music and conversation, please make a gift today.