Southwest Detroit Community CARE mutual aid group uplifted community during the pandemic

Two years ago, Gabriela Santiago-Romero and other Latina organizers came together as Southwest Detroit Community CARE, or Southwest CARE, to help those in need during the early days of the pandemic.

“Communities of Hope” features Detroiters from communities of color who have been looking for ways to persevere during the pandemic.

When Michigan went into a lockdown in March 2020 because of COVID-19, Gabriela Santiago-Romero jumped into action. Her grassroots effort bloomed into Southwest Detroit Community CARE, a mutual aid group to help residents in need.

The Southwest Detroit resident was recently elected as the Detroit City Council member representing District Six, which comprises residents from Hispanic, African American and Middle Eastern communities.

She previously served as the Policy and Research Director with We The People, a Michigan-based nonprofit organization that works to build collective economic-political power for working-class people.

Two years ago she and other Latina organizers came together as Southwest Detroit Community CARE, or Southwest CARE, to help those in need during the early days of the pandemic.

“I was petrified for my community because I was already hearing immigrant mothers were being fired, told not to return. There were parents without driver’s licenses that were scared to go to grocery stores. They were just already compounding issues that we’ve already had. COVID just made worse,” she says.

Santiago-Romero initially started by creating a Google Form where people could send in requests for what they needed such as money to pay rent or buy groceries.

She says she knows all too well what it’s like to need help as someone who grew up in a working-class, single-parent home. Santiago-Romero recalls the moment she realized she was “poor,” when she asked her mom to buy a pair of sneakers but the family couldn’t afford them.

“It was really later in life that I realized that my mom went to the church every week of every few weeks to get a box full of food that she paid $15 for. We were able to receive certain resources and services that allowed us to to live our lives with dignity. Many times it was because our salary was less than $20 to 30,000 a year,” says Santiago-Romero.

“I don’t believe in scarcity. The resources are out there. Somebody has it and it’s about making those connections, forming those relationships, and really working together.” —Gabriela Santiago-Romero

Santiago-Romero says the group of Southwest CARE volunteers blossomed to about 20 or so at any given time. They rolled up their sleeves and got to work from March to August 2020, raising $80,000 for 300 families.

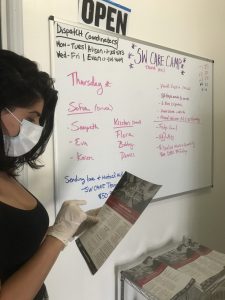

Intake coordinators would call people and find out exactly what they needed. Some volunteers were tasked with contacting residents who needed Spanish or Arabic translators. Dispatch coordinators would then match volunteers with tasks such as packing boxes, shopping or dropping off groceries.

Santiago-Romero’s office became a hub for diaper distribution where families could pick up diapers every two weeks drive-through style.

Several coordinators took parts of different tasks to keep things flowing. They would meet weekly via Zoom to keep things on track.

Angela Gallegos worked as one of the project managers for the group. She was one of the primary people who set up shop at an apartment on Vernor Highway. The location called the Southwest Care Camp became a makeshift food pantry location where care packages were put together. Many of the other volunteers worked from home.

Gallegos says in the early days of the pandemic people struggled because nonprofits were closed.

“We knew that things needed to flow still for our community, especially those who are undocumented … underserved and just needed resources and couldn’t get to them because we were all at home,” says Gallegos.

Gallegos says volunteer days began with checking the intake form creating boxes, and handing them off to volunteers to drop off.

Some of the people they assisted were undocumented people who did not have access to federal assistance, seniors who may have slipped through the cracks, or those who lost their in-person jobs.

“We were cutting checks for like, a couple hundred dollars so people could pay their bills. We were helping with food and we were delivering groceries to people’s doorsteps,” she says.

They did this by working with a fiduciary and creating a trust fund for people to take out money.

Santiago-Romero says organizers and donors who received a federal assistance check during the pandemic donated all or a portion of their check to the mutual aid group.

“I don’t believe in scarcity. The resources are out there. Somebody has it and it’s about making those connections, forming those relationships, and really working together,” she says.

Vicente Jaramillo is the human resources manager of Fresh Pak, a produce packing company in Southwest Detroit. It provides freshly cut produce upwards of 60,000 units per day to companies like Kroger around the nation.

During the pandemic, Fresh Pak donated produce for those in need to support Southwest CARE. He says it created a ripple effect in the community.

“Just because we actually donated, we actually had people to come apply and actually start working for us,” he says.

Jaramillo says the company employs about 315 people locally. He says Southwest CARE provided much-needed resources to undocumented families.

“It’s a great organization. There isn’t really enough programs that actually cater to the undocumented community and basically, that’s the community that suffers the most. And to be honest, that’s the backbone of the whole country … undocumented workers,” says Jaramillo.

Gallegos says Southwest CARE gained traction as a group that’s “by the people, for the people.”

“When we started to move in … and organize ourselves … without the help o f… nonprofits or the companies … more people wanted to just organize more resources,” she says.

Gallegos says people communicate via social media or on WhatsApp to connect with the organizers, by word-of-mouth. Like Gallegos, Santiago-Romero says being a grassroots effort helped speed things along.

“We are community members and for us we actually think it’s very powerful for people who aren’t in a nonprofit, who aren’t corporations to come together and support their neighbors in this way,” she says.

Santiago-Romero says at times it was challenging to keep up with the mutual aid work while working full time during the pandemic. The group eventually applied and received a grant.

“It’s a great organization. There isn’t really enough programs that actually cater to the undocumented community and basically, that’s the community that suffers the most. ” — Vicente Jaramillo, Fresh Pak

“It was making sure that our people internally were also OK enough to do the work because we were all a part of the COVID process and experience and it was hard for all of us,” she says.

Santiago-Romero says people looked out for each other to stay afloat during the pandemic.

“Our businesses, many of them did not fall through. Many of our urban neighborhoods still have families living there.”

She says Southwest CARE is dormant now, as state and federal resources have opened up again, and are more readily available. They are ready to pick up and help residents again when and if there is a need. Just last summer they helped about a dozen people clean out their basements following catastrophic floods across the region.

Santiago-Romero initially jumped into action to assist those in need during the pandemic, from people who were undocumented to those who lost their jobs. Her initiative quickly formed into a volunteer-based mutual aid group providing groceries, money and diapers. Southwest Detroit Community CARE helped 300 families, showing people they could hold onto hope and each other.

A note of disclosure: Angela Gallegos is a former WDET employee.

Trusted, accurate, up-to-date.

WDET strives to make our journalism accessible to everyone. As a public media institution, we maintain our journalistic integrity through independent support from readers like you. If you value WDET as your source of news, music and conversation, please make a gift today.