Carl Bernstein’s “Chasing History” chronicles his journalism career and critiques modern newsgathering

Carl Bernstein covered the civil rights revolution, the anti-war movement, the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and more as a young reporter. “The connections and resonance with today, it’s all about the trade of news,” he says.

One of the nations’ most celebrated journalists says those trying to find “the best obtainable version of the truth” today should look to those who searched for it in the past.

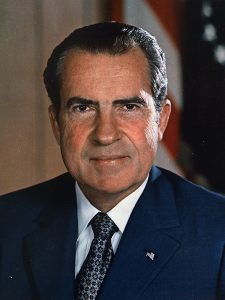

Carl Bernstein defined investigative journalism for generations of Americans. At the Washington Post in the 1970s, Bernstein and Bob Woodward exposed the Watergate scandal that drove former President Nixon from office.

Now Bernstein is defining how his reporting skills came to be. But he says his new book, Chasing History: A Kid in the Newsroom, is far from just “an old man looking back.”

Instead, Bernstein says the story of his birth as a journalist at the now-defunct Washington Star newspaper is both a critique of newsgathering and the journey of a kid reporter covering some of history’s most important stories.

It’s also evidence of the thread connecting his time at the Star to the seminal events chronicled in the 1976 movie All the President’s Men. And, eventually, to the rise of Donald Trump and so-called “fake” news.

Listen: Carl Bernstein’s coming of age in the newsroom.

Carl Bernstein (edited for clarity): I went to work, at age 16, at perhaps the greatest afternoon newspaper in America. And even though this book is written from the point of view of the kid at the time, you can see the connection directly to All the President’s Men and Watergate. Because everything that I knew when Woodward and I started to cover the Watergate story — I was 28, he was 29 — I brought with me from the Star. The basic elements of the kind of reporting we did in Watergate you see in this book as I’m learning them. Getting to go out in the streets and alleys of the city and meet sources and make sure that the stories are pinned down with multiple sources, knocking on doors. As well as this time in America, a time of Jack Kennedy’s election, which I actually covered parts of. His assassination, which I covered. The civil rights revolution, which I was able to cover beginning when I was 16 and 17. The anti-war movement, the build-up in Vietnam, the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which now we see being obliterated by the Republican Senate of the United States. So the connections and resonance with today, it’s all about the trade of news.

Quinn Klinefelter, WDET News: It’s a very different time than now. I’ve talked to people that worked in older newsrooms. They would say that one of the things they missed going in was that they never heard the clacking of the typewriters anymore, it’s all on computer. It was a very visceral experience, it seems, back in the day.

Well, it was. The most visceral thing of all, though, is how you get out of the office, meet people, amazing people, your sources. You’re learning about stories. That hasn’t changed, except to the extent that in so many newsrooms today we have too many people who use the internet, particularly, as an excuse not to do real reporting, what Woodward and I came to call “the best obtainable version of the truth.” But to get to that point of the best obtainable version of the truth, you can’t do it with Google, you can’t do it with Wikipedia. Those are great tools. And it would have been wonderful during Watergate, we would have saved a lot of time, if we could get background information so quickly. But you gotta get out of the office. And there’s less and less getting out of the office being done, as too many reporters today think, “Oh, get the story by going online.” And [they] don’t do that persistence, don’t go visit people in their homes at night, like we did in Watergate, like we did it at the Washington Star, to get good stories. Don’t see them in their offices where they’re under pressure from their bosses. At the time I went to work at the Star I had one foot in the pool hall, one foot in the juvenile court and one foot, a little bit, in the classroom.

There are some people that will say with the rise of citizen journalism, that this is a renaissance of sorts. Because anybody with a cellphone or video can go out there and become, quote, a “reporter.”

No, I don’t think it’s a renaissance. I think that citizen reporting has a place. But it’s not curated and presided over by anything but the citizen himself or herself. What happens at real news institutions is you have a chain of command, you have a set of standards, hopefully connected to the best obtainable version of the truth, as the primary purpose of what you’re doing in this news organization. And there might be some great stories done by citizen journalists. But there’s also a lot of crap out there. And a lot of it is witness. It’s not really reporting in the classic sense, it’s not really journalism, but it’s witness. And it’s great to have. But you raise a point that gets to another. And that is how many consumers of so-called news and information are not looking for the best obtainable version of the truth. But rather, they’re looking for information that reinforces what they already believe, their previously held ideological beliefs, political beliefs. They’re not looking for anything except ammunition.

Yeah, here in Detroit, there’s been so many people who are worried about the [COVID-19] vaccine, in part because they have these various forms of information that will tell them things that that, as you say, some of them want to hear. And others will say, “Well, that’s fake news. And we can’t believe what the government says.” When you were doing Watergate, one of the things, at the beginning especially, was that you guys in the Post were out there pretty much on your own. And the White House was coming back and saying, “The McGovern campaign and their partners-in-crime, the Washington Post.” And you guys were pretty well out there for quite a while by yourselves. How did you show that you had the best obtainable version of the truth?

We kept reporting. Day after day. And got the information going to all these sources. Yes, the White House and the Nixon people were very successful for a long time in making our conduct — Woodward, myself, Ben Bradlee, the editor of the Post — making our conduct the issue in Watergate rather than the conduct of the president and those around him. We see the same thing happening in the Trump presidency and those who support Donald Trump. But what we did is we kept reporting. So after a month or two of denials from the White House about this “third-rate burglary,” we did a story that said there had been a secret fund that five people controlled that paid for the bugging at Watergate and other undercover activities. And so that chipped away at the White House denial. And more and more people came to say, “Oh, well, maybe there’s more to it.” Then we wrote a story in October, a few months after the break-in, that really made sense of Watergate, saying that it had been just one act in a vast campaign of political espionage and sabotage directed from the Nixon White House. Well, then that made the denials even less believable. What happened in Watergate is there came to be a consensus in the country about the truth of what we were writing.

Trusted, accurate, up-to-date.

WDET strives to make our journalism accessible to everyone. As a public media institution, we maintain our journalistic integrity through independent support from readers like you. If you value WDET as your source of news, music and conversation, please make a gift today.