Hamtramck Ramps Up Efforts to Reach Bangladeshi Voters During Elections

The City of Hamtramck says it’s working to reach its Bangladeshi voters, but community leaders and voters say there is more work to be done even a decade after the city began providing the ballots in accordance with the Voting Rights Act.

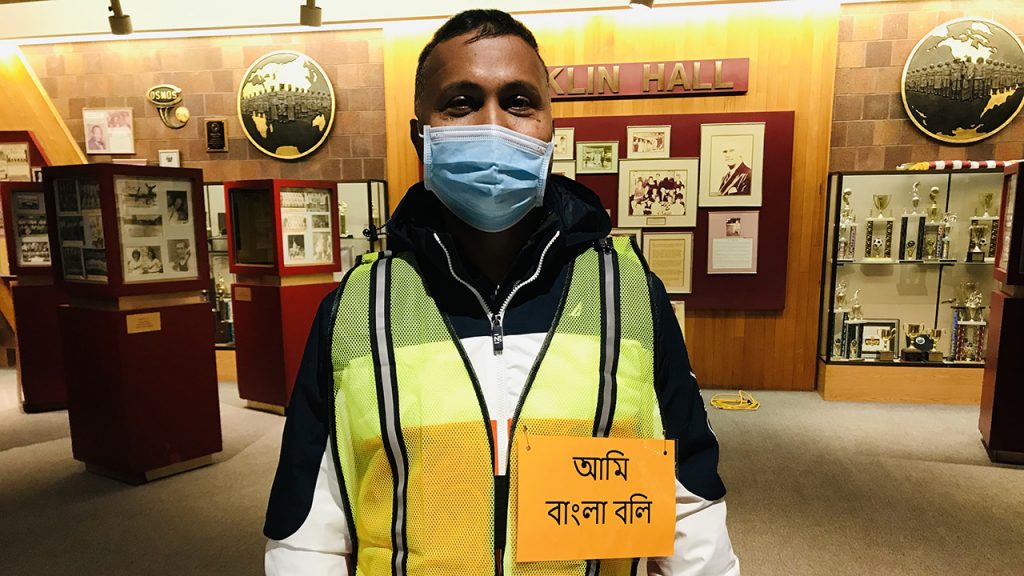

As voters walk into the Hamtramck Community Center, Ali Newaz greets voters and directs them to one of three precincts. He smiles behind his mask. He’s wearing a bright orange sign on his multicolored windbreaker that reads “I speak Bangla.”

Hamtramck City Manager Kathy Angerer says the sign is part of an effort to reach out to Bangladeshi voters. Officials are also working to provide more copies of ballots in Bengali or Bangla based on the area’s Bangladeshi population numbers from the 2010 Census.

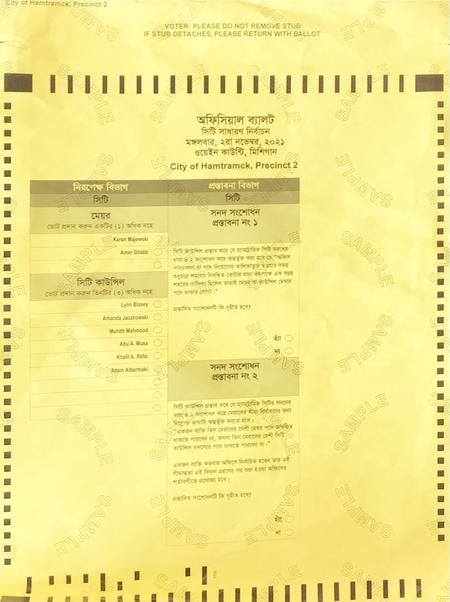

“We had a lot of limited English proficient Bengali speaking persons. So, in order to accommodate their voting and make that a process that works better for them we have started having Bengali ballots. A lot of our materials, all of our election materials are translated into Bangla,” says Angerer.

The City of Hamtramck says it’s working to reach its Bangladeshi voters who speak Bengali, also known as Bangla. Officials are trying to provide translated election materials. But community leaders and voters say there is more work to be done even a decade after the city began providing the ballots in accordance with the Voting Rights Act.

Hamtramck has been required to provide them since October 2011 due to the city’s growing Bangladeshi population, now hovering near 30%.

During the 2010 Census, community leaders encouraged residents to write in “Bangladeshi” for ethnicity, instead of “other” on the Census form leading to the change. Angerer says she hopes that’s just the first step.

“What I’m hoping is that it will broaden and we’ll do that same for Arabic community and other minorities that grow in Hamtramck,” she says.

In June, the city of Hamtramck was sued by the Asian American Legal Defense and Education Fund on behalf of the grassroots community organization Detroit Action and Rahima Begum, a Bangladeshi voter who wasn’t able to cast a Bangla ballot in the 2020 elections.

Laura Misumi was the Managing Director at Detroit Action earlier this year when the suit was filed. She says community organizers notified the city that Bangladeshi voters were not receiving proper assistance at the polls.

“We then reached out to AALDEF, the Asian American Legal Defense and Education Fund, about the possibility of trying to find a language access voting rights lawsuit against the city of Hamtramck for failure to provide this language access,” she says.

The lawsuit states only Republican ballots were available to voters during the presidential primary and Democratic ballots were buried under other materials, there wasn’t signage providing information in Bangla as required by the Voting Rights Act, and poll workers weren’t trained to ask Bangladeshi voters if they’d like to vote in Bangla.

The judge passed a consent decree in July requiring Hamtramck to beef up its efforts. Part of the decree requires all election materials to be translated into Bangla, the city has to hire a Bengali election coordinator, and officials have to work with a community advisory committee.

Bilal Hammoud is the Public Engagement Associate with the Michigan Department of State. He is the chair of the state’s language access task force.

He says he does outreach work to reach communities “that traditionally face more than the average barriers to access,” like connecting people to state resources for voting, housing and jobs.

Hammoud says while some people have barriers such as not having official IDs to vote non-English speakers, immigrants and refugees may need information in their native languages to effectively cast a ballot.

“And so in communities like Dearborn and Dearborn Heights and Hamtramck, we have to put an extra effort to ensure that these communities are getting that representation and the equitable access,” he says.

Abu Musa is a former Hamtramck City Councilman who served two terms in Hamtramck. He lost a bid for reelection this year. He says he voted in Bangla.

“People can vote in English also. When people encourage you to [use] Bengali ballots, as a Bangladeshi American it is my pride to vote with the Bengali ballot,” he says.

“People can vote in English also. When people encourage you to [use] Bengali ballots, as a Bangladeshi American it is my pride to vote with the Bengali ballot.” –Abu Musa, former Hamtramck City Councilman

Musa, who reads and writes fluently in Bangla, says in previous years there were errors on the ballots because they were poorly translated.

Hamtramck says fewer than 10 people voted in Bangla in the general election this month. That compares to just two people requesting ballots in Bangla between 2012 and 2020, according to the City Clerk’s office.

Musa says it’s important for people to have these ballots because members of the Bangladeshi community have had to fight for representation.

As people left the polling place earlier this month, many residents said they didn’t vote in Bangla. Some said they didn’t know they could request the special ballots, but they did notice the translators wearing bright orange signs who were there to help.

Community organizers say they are working with Hamtramck officials to take steps to do better — one election at a time.

Listen: Hamtramck works to increase voter access among Bangladeshi residents after lawsuit.

Trusted, accurate, up-to-date.

WDET strives to make our journalism accessible to everyone. As a public media institution, we maintain our journalistic integrity through independent support from readers like you. If you value WDET as your source of news, music and conversation, please make a gift today.