How Coronavirus Changed Detroit’s Water Shutoff Policy

The collision of two public health emergencies – COVID-19 and water accessibility – prompted government action. Some wonder what took so long.

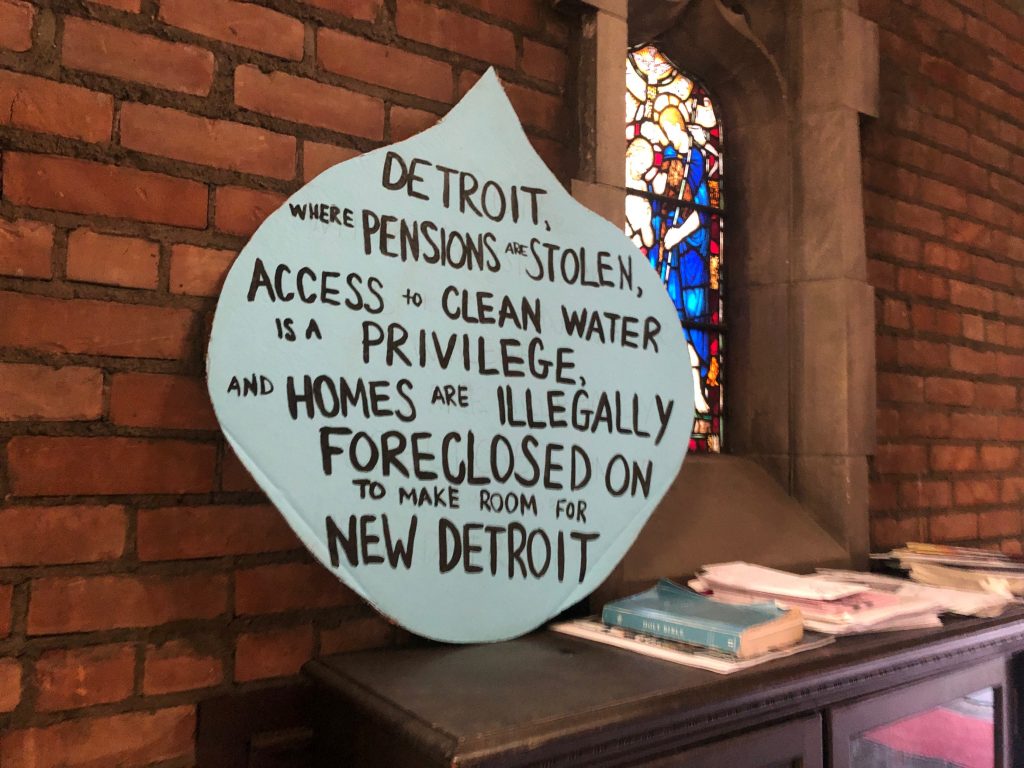

Late last year, officials in Detroit committed to ending the city’s water shut-off policy. The austerity measure was put in place during bankruptcy as a cost-savings measure. Tens of thousands of residents have had their water shut off in the years since. Throughout 2020, activists were quick to call attention to how a coronavirus outbreak would exacerbate a health crisis already years in the making. They did so weeks before any state or local action was taken.

“We’ve been preparing for this moment for decades.” – Monica Lewis Patrick, We the People of Detroit

A Crisis Before an Outbreak

It’s the end of March in Corktown and a group of volunteers are unloading packages of water bottles from a blue Absopure truck. They’re with We the People of Detroit, a civil rights organization that’s been working on the city’s water accessibility crisis for more than six years.

The volunteers have stacked hundreds of jugs and bottles of water inside a church, as they get ready to deliver them to residents across the city. The water relief effort is not new to the pandemic. We the People of Detroit started doing this sort of work under Kevyn Orr’s emergency management of the city in the last decade when the Detroit Water and Sewerage Department began penalizing the non-payment of bills by shutting off service to occupied homes. Despite federal lawsuits and condemnations from the United Nations, the policy remained in place as the city approved a plan to resolve its bankruptcy debts in 2014. More than 20,000 Detroiters lost access to running water that year.

Monica Lewis Patrick, who leads We the People of Detroit, says it’s been many more since then.

“What we know is since 2014, over 161,000 households have been shut off from water in the City of Detroit,” says Lewis Patrick.

Lewis Patrick says the worsening coronavirus outbreak in the U.S. this year has made securing bottled water harder. But overall, she says she’s not surprised about the collision of two public health emergencies.

“You’ve had decades of divestment and oppression and capitalist agendas taking precedence over people. So we’re not shocked in Detroit,” Lewis Patrick says. “We’ve been preparing for this moment for decades.”

The progressive outreach organization Engage Michigan helped petition Governor Gretchen Whitmer, urging her to intervene before an outbreak hit the state. The group was concerned that Detroiters would not be able to follow basic health guidelines if they did not have access to running water.

“We know that we need people to have access to clean, affordable water in their homes in order to wash their hands,” Engage Michigan’s Kim Hunter told WDET in February. “That is one of the number one recommendations.”

Hunter says the connection between water shutoffs and illnesses is well documented, citing research from the Henry Ford Global Health Initiative.

“What that showed was that there was a 150% increased chance that people would contact things like shigellosis, campylobacter, and giardia, which are diseases that are associated with water or having a lack of water,” said Hunter.

Government Action Stops Shutoffs as Pandemic Begins

Whitmer stopped shutoffs statewide through an executive order a month after the coalition’s plea for action. On March 9, the day before Michigan reported its first case of COVID-19, Detroit officials suspended the city’s shutoff policy. The Detroit Water and Sewerage Department announced a plan to restart water at homes that did not have service, establishing a reduced $25-a-month bill. That reduced rate was made possible by state funding.

In the first month of the program, the utility received 25,000 calls to join, but most applicants did not qualify. The COVID-19 Water Restart Plan does not apply to homes with running water that are not at risk of a service interruption for non-payment.

Water department director Gary Brown says to date, 1,300 occupied homes have had their service restored. Many have had their plumbing repaired by the city. And he says the utility offers other financial assistance as well.

“By the end of December, $22 million is expected to be spent. $15 million of which will go towards bill credits to nearly 50,000 Detroit households,” Brown said last year.

Even with the aid, Brown says 18,000 homes in Detroit still regularly struggle to keep their water running. State legislators agreed to extend Michigan’s shutoff moratorium until the end of March 2021. But Mayor Mike Duggan is committing to eliminating the policy forever. He says the city has enough federal, state and private charitable funding to stop shutoffs for the next two years.

“In addition to that, we got help from the Great Lakes Water Authority,” Duggan said during a December press conference. “With that fund, we now have enough money we believe to cover the costs of anybody who can’t afford to pay their water.”

Two Years to Figure Out a Plan

Duggan says the city has until the end of 2022 to find a permanent solution and will lobby the incoming Biden administration to draft a plan for water security in Detroit and across the country. In its latest coronavirus relief package, Congress approved $638 million in funding for low-income households in need of water assistance.

Detroit’s former health director Abdul El-Sayed is also getting involved. He says water support could be funded in the same way as the national Low Income Heating Assistance Program.

“There are a number of different ways to be thinking about this problem,” El-Sayed says. “Some of those are federal, some of those are state, some of those may be local.”

“Some people that have paid their bills over and over and over again and got on these payment plans and got on assistance still ended up in trouble.” — Meeko Williams, Hydrate Detroit

But not everyone is convinced that the Duggan administration is making a good faith effort to stop the shutoffs. Meeko Williams leads Hydrate Detroit, another water accessibility group.

“This is more political posturing for his re-election campaign,” Williams told WDET’s Detroit Today.

Williams says the grassroots water security movement was not given prior notice of the mayor’s December announcement on a shutoff moratorium and has been left out of planning efforts. He says the city’s current support programs punish residents who miss payments, so groups like his step in.

“Some people that have paid their bills over and over and over again and got on these payment plans and got on assistance still ended up in trouble,” Williams says. “The policies were not correct.”

Activists like Williams say the Duggan administration does not have to wait two years to put a plan together. Detroit is in the middle of revising its charter and could add new legal language around a People’s Bill of Rights. Some hope that’s how water accessibility can become a basic human right in the city. And that’s something the mayor could endorse. Williams says he won’t be satisfied with a solution unless it includes water relief amnesty.

“You cut the arrears and you erase the debt,” Williams says. “You erase the debt clean and you zero out all the residents, homeowners that have high water bills back to zero so that we can start over.”

Trusted, accurate, up-to-date

WDET is here to keep you informed on essential information, news and resources related to COVID-19.

This is a stressful, insecure time for many. So it’s more important than ever for you, our listeners and readers, who are able to donate to keep supporting WDET’s mission. Please make a gift today.