The 1974 Supreme Court Ruling On Detroit School Busing That Worsened Segregation

As white flight from Detroit took off in 1970’s Michigan, the NAACP sued to combat regional school segregation. Justice Thurgood Marshall said the final ruling perpetuated “the very evil” Brown v. Board of Education was meant to stop.

It’s the early 1970’s. The City of Detroit is still licking its wounds after the civil disturbance in July of 1967. White flight to the suburbs is in full effect and, as those families moved out, Detroit’s racial composition began to change.

One of the places that was apparent was in the city’s public school system. The NAACP filed a suit challenging lawmakers on the issue, alleging that school inequality reflected the various housing policies and economic redlining present in the city.

“Nobody argues the fact that there was discrimination. The whole controversy in Milliken deals with the remedy.” – Peter Hammer, Damon J. Keith Center for Civil Rights

The key question: How do you integrate a district that, on its own, is becoming less diverse? The solution, known as interdistrict busing, where Detroit public school students cross city borders to attend schools in the suburbs and vice versa, led to the 1974 US Supreme Court case known as Milliken v. Bradley.

Peter Hammer is law professor and director of the Damon J. Keith Center for Civil Rights at Wayne State University. He says the NAACP argued that school integration could never occur where those discriminatory factors are present.

“Nobody historically argues about the fact that there was discrimination,” says Hammer. “The whole controversy in Milliken deals with the remedy.”

101.9 WDET’s Alex McLenon spoke with Hammer about Milliken v. Bradley, the evolution of regional busing in southeast Michigan, and the lasting legacy of the decision on Detroit Public Schools.

Click on the player above to hear how Milliken v. Bradley entrenched segregation in southeast Michigan, and read the history below.

Regionalism Becomes a Force for Integration

“I could bus [students] all I want within the boundaries of Detroit, but as a result of white flight that would never produce integration.” – Peter Hammer, Damon J. Keith Center for Civil Rights

The movement of Detroit’s white population to the suburbs, known as ‘white flight’ across the nation, had left the city, and it’s schools, majority-black.

“White flight had been so intense,” Hammer says. “I could bus [students] all I want within the boundaries of Detroit, but as a result of white flight that would never produce integration.”

The desegregation case was first ruled on at the District Court level by Judge Stephen Roth.

Because of the city’s racial makeup and the ongoing trend of white flight, Hammer says Roth believed a desegregation plan for Detroit schools would have to include the suburbs.

“He said we really look at this as a regional problem. Racism is a regional issue, segregation is a regional issue, and therefore I want to have a regional remedy.”

The solution Roth came up with was interdistrict busing, a plan where inner city and suburban students would be bused to school together with a quota reflecting the region’s diversity — not just the individual districts.

The US 6th Circuit Court of Appeals agreed with Judge Roth and upheld the intrerdistrict solution. But suburban residents were unhappy, and the Milliken case made its way to the US Supreme Court.

Separate but Equal?

“If we are to allow the Courts to engage in social goals rather than confine themselves to the scope of the remedy that the violation requires, we allow them to trample on the rights of clients such as mine here today.” – Frank Kelley, former Michigan Attorney General

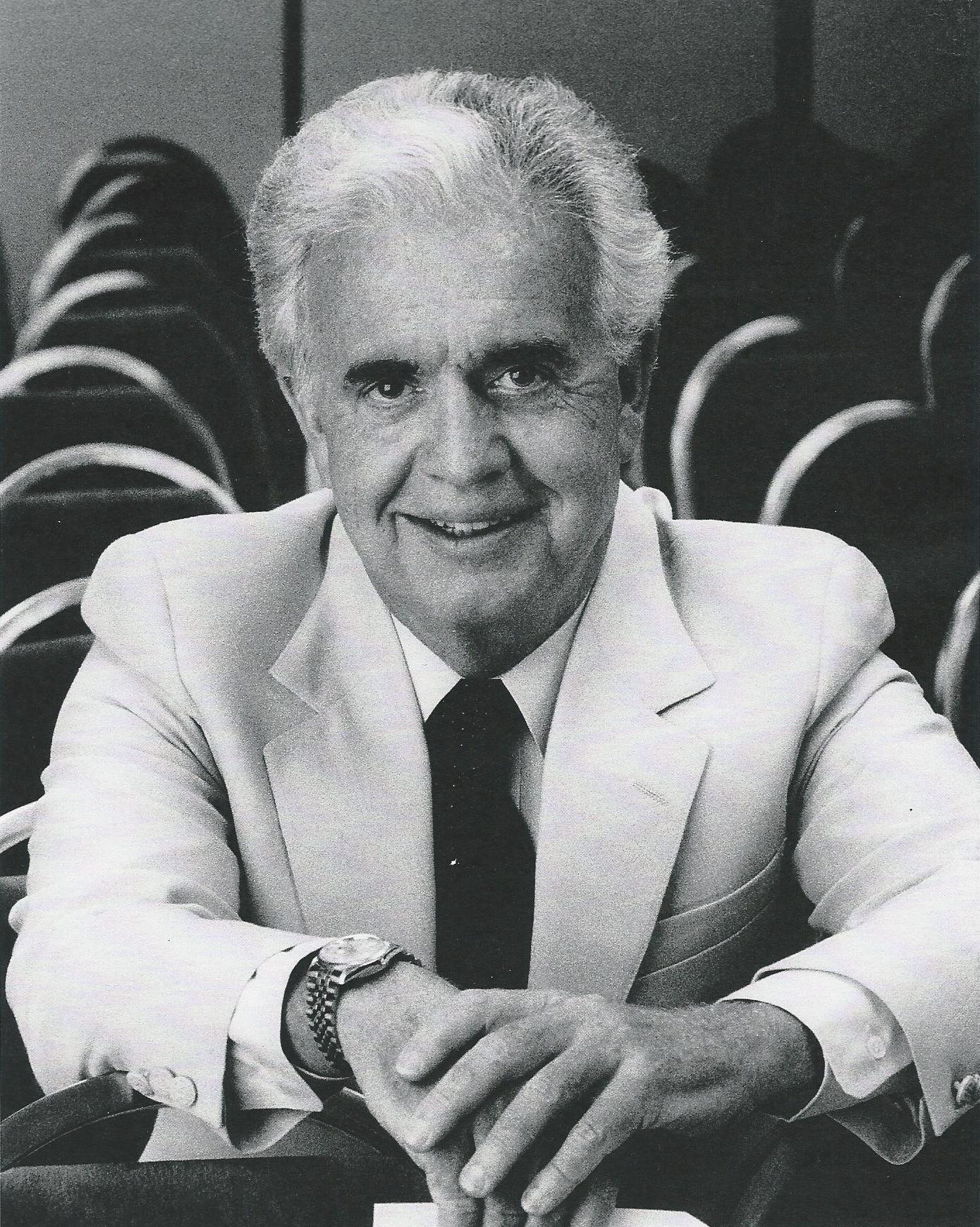

Once on Capitol Hill, Michigan’s Attorney General Frank Kelley brought forward the case of suburban schools.

He argued that because there was no proof of intentional segregation in the suburbs, they should be excluded from the solution.

Peter Hammer says that notion reflects a popular northern tone on desegregation.

“There’s an old adage that in the South: You can be close, and a lot of the social relationships were fairly intimate, but you can’t be equal. In the North, the old adage goes that you can be equal, because we in the North don’t like to discriminate, but you can’t be close.”

Hammer says the Milliken case was compared to one that was heard by the Supreme Court just a few years prior: “Swann versus Charlotte-Mecklenburg.”

“What the Supreme Court said in Swann,” Hammer says, “is that busing is an appropriate remedy. And if you look at the facts of Swann, that busing was happening at a huge geographic boundaries.”

Swann ruled that busing could be used to desegregate schools if the schools were all in the same district. Because that wasn’t the case in metro Detroit area, the Supreme Court overturned the multiple district solution in a 5-to-4 vote.

“Not Understanding the Real Problem”

“Without an interdistrict violation and some interdistrict effect, there is no constitutional basis for an interdistrict remedy.” – Justice Warren Burger, US Supreme Court majority opinion

The ruling set a standard that desegregation was not a regional responsibility.

However, in arriving at that conclusion, Hammer says the Supreme Court misunderstood key context from the Swann case.

“In Charlotte and Mecklenburg County, and in North Carolina more generally, if I have substantial sprawl and white flight they continuously change the school district,” says Hammer. “So at the end what you had was a regional unit.”

Therefore busing within the districts was a reasonable solution in North Carolina, because boundary lines were already changing to reflect the region’s diversity.

“And this doesn’t get talked about in the case,” Hammer says. “Which really [shows] that the court is not really understanding what the real problems were.”

Marshall’s Dissent

“Our nation I fear will be ill served by this Court’s refusal to remedy separate and unequal education. For unless our children begin to learn together, there is little hope our people will ever learn to live together and understand each other.” – Justice Thurgood Marshall, US Supreme Court dissent

The ruling meant that as white families left Detroit for suburban school districts, the largely African American community still in the city was just left there. That inaction essentially allowed the city and the suburbs to segregate themselves.

“Thurgood Marshall wrote an amazingly powerful, dissent saying is that if you don’t provide a remedy here, you have no way to deal with the segregation,” Hammer says.

Read Justice Thurgood Marshall’s dissent in Milliken v. Bradley

“There was a concurring opinion where the judge just kind of throws up his hands and says ‘we can’t even begin to deal with this. These are unknowable forces. Right? Unknown and unknowable forces,” Hammer says.

Justice Potter Stewart submitted a concurring opinion on the Milliken v. Bradley decision. In his written statement, he recognized that white flight and what he called ‘private acts of racial fear’ were causing segregation in Detroit schools.

Even so, Stewart still voted against interdistrict busing.

45 Years Later, a Suffering School District

“The very evil that Brown was aimed at will not be cured, but will be perpetuated.” – Justice Thurgood Marshall, US Supreme Court

Some felt the outcome stood in the face of past desegregation rulings, like Brown v. Board of Education.

Fast forward to present day and Hammer says the result of the Milliken case is visible in Detroit public schools.

“You think about the state of Detroit schools and the whole collapse as a result of failed state policy in terms of governance and finance, has created a school district that is completely dysfunctional and is not serving our children,” Hammer says.

He says the outcome is still being fought through cases like the ‘Right to Literacy,’ which is currently making its way through the US Court of Appeals. It asserts that literacy is the right of a student who attends school, attempting to hold lawmakers responsible for funding needed to raise the reading level at Detroit schools.

If successful, the ‘Right to Literacy’ case could help make up ground the district lost 45 years ago, as result of Milliken v. Bradley.

Support the news you love.

Here at WDET, we strive to make our journalism accessible to everyone. As a public media institution, we maintain our journalistic integrity through independent support from readers like you. If you value WDET as your source of news, music, and conversation, please consider making a gift today. Even $5 a month helps!