Taking Public Stage Helps Muslim Woman Recover from Sexual Trauma

Play performance in Dearborn tackles taboo issues and other stories of the community.

Click on the audio player above to hear the story.

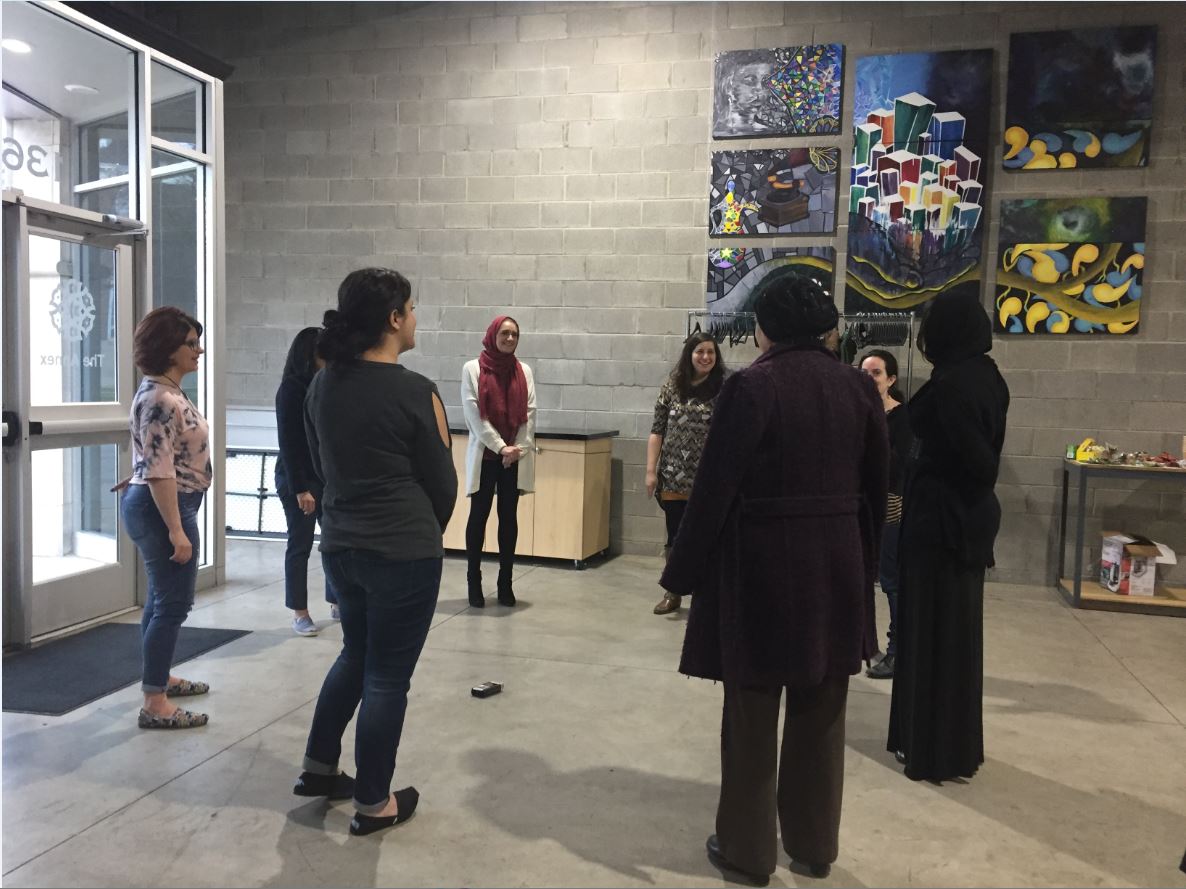

Six women formed a circle on stage and warmed up for a rehearsal by making nonsensical sounds: “zip;” “zap;” “zop.”

They’re practicing to perform the original play: Undesirable Elements Dearborn. Most of these women have never acted before.

But that doesn’t matter because in this performance they’ll be playing themselves.

The script is based on details of their lives, woven into a chronological narrative that is telling part of the community’s story as well.

Staff at the Arab American National Museum invited the New York-based theater company, Ping Chong + Company, to Dearborn. The company has spent decades using this interview-style format to give the stage to potentially misunderstood communities around the world.

Associate Director Sara Zatz, who is also co-writer and co-director of this performance, said there’s power in the fact that the stars aren’t actors.

“I find that this format is so moving. People in audiences connect with it differently than when they might think of a traditional play because what you have are the real people on stage telling their own stories,” she said.

The Muslim women in this show include a graffiti artist, a hijab-wearing prom queen and a punk rock-loving immigration attorney.

There’s also Salam Aboulhassan. She’s working on a doctorate in sociology at Wayne State University.

Aboulhassan was born and raised in Dearborn. She admits part of her feels the need to protect her community’s image from being mischaracterized as overrun by Islamic extremists.

“But I just have to say that I think it’s more important to tell the stories of women within the town,” said Aboulhassan during the first week of rehearsals. “We’re constantly fed that we have to protect the town from these outside forces. Sometimes we’re silenced as a result.”

Aboulhassan went through traumatic experiences as a child that she felt unable to share with anyone. During the early stages of the play’s development, she wasn’t ready to reveal what happened yet either. She will, however, talk about it during the play. And that, she said, makes her worried that audience members will victimize her.

“I say victimized like that, nobody’s going to attack me, but people are going to victimize me. I’m not looking for pity. I think that’s actually what I want people to know is that this is actually coming from a place of intense power,” she said.

Related: Upcoming Play in Dearborn to Feature Arab-American Voices in Their Own Words

On opening night, the house was packed. The lights came up to reveal Aboulhassan and her five co-performers seated on stage. Half of these women chose to cover their hair for religious reasons. Aboullhassan wore hers down, in wavy layers that flowed past her shoulders. She had on skinny jeans and muted high heels.

The performance kicked off with a lively Dearborn trivia section.

“Who is Simon Baz?” one of the performers asked.

Another answered, “The first Arab-American superhero in comic history. And he’s from?”

“Dearborn!” the cast said in unison.

Click here to listen to unedited interviews with the cast of Undesirable Elements Dearborn

Before the audience knew it, the storyline shifted from a focus on the city to an intimate look at significant moments in the cast members’ lives. One told of getting her parents’ approval to go to college in the 1970s. Another shared that her mother, suffering from post-partem depression, took her own life.

When it became Aboulhassan’s turn, the women next to her grabbed her hands.

“I am nine years old,” she began. “A close family member begins sexually abusing me. Before the abuse, I am a talkative, rambunctious child. When the abuse begins I am silenced.”

Aboulhassan let go of her castmembers’ hands and told the audience that the abuse went on for two years. Then it was 25 years before she told anyone about it, she said.

After the show, Aboulhassan was milling around with the audience, holding a bouquet of flowers.

“Before that I wasn’t sure how I was going to feel. I don’t know if anybody can ever really explain the sense of freedom from being able just to say that out loud,” she said. “I don’t know if I’ll ever forget this type of freedom.”

Aboulhassan said this was the first time she publicly shared her traumatic experience. She said she felt a bond with her castmates who also revealed difficult and celebratory moments with the audience.

The show’s director, Zatz, said the play is intended to confront stereotypes about Dearborn that might be held by outsiders. But, she said, the play is also intended to shine a light on the Arab American community from within.