Is the Tax Foreclosure Process Good for Wayne County but Bad for Detroit?

Today some Wayne County homeowners will have their houses added to the auction list.

Annie Perry sits in a bejeweled knit cap, waiting for her number to be called at a foreclosure prevention meeting.

It’s being hosted by the nonprofit, United Community Housing Coalition. Perry, an 83-year-old Alabama native, is facing tax-foreclosure on the house she and her husband bought in Detroit in 1970. Her southern manners show through when she talks about the people she’s met with at the Wayne County Treasurer’s office.

“Very sweet girl,” Perry says. “All of them sweet down there. I want them to know that. Everybody’s nice.”

But Perry won’t sugarcoat the hassle of dealing with late taxes.

She turns her attention to a pile of documents spread out on a table. “Look at all the papers! And that’s just some of them, you saw my red bag. Oh my god!” she says with exasperation. The pages in front of her are only a portion of what she has collected.

The Scope of Tax Foreclosures

Perry and about 17,000 homeowners in Wayne County have been notified that their properties are facing tax foreclosure this year because they owe property taxes from 2014 or earlier. When these homeowners were first alerted — which was supposed to happen two years ago — they were told by the county treasurer that if they didn’t pay what they owed, it would cost them.

“Now for every day, or every month really, there is a penalty, an interest that is being charged for the delinquency,” says Raymond Wojtowicz, Wayne County treasurer from 1976 to 2015. “So the encouragement to everyone is pay your taxes as soon as you can and avoid foreclosure.”

When in office his mantra was, “We don’t want your home, just your taxes.”

If Perry pays her taxes or gets on a payment plan, she will retain the title to her house. If she doesn’t, the house will be listed for sale in the county’s September auction. If a buyer purchases her house in the auction, the money will go to the city and the county to help cover the unpaid taxes and fees. She won’t see a dime.

More than 160,000 homes in the county have been tax-foreclosed since 2002. The process is mandated by state law, and it’s complicated.

Bridge Magazine explains the process and its financial effects on municipalities. Click here to read the piece “Sorry we foreclosed your home. But thanks for fixing our budget.”

But here’s one thing that’s important: the law has not only helped cities and counties recover unpaid tax money, in Wayne County, it’s brought in additional revenue for the troubled county budget. According to documents analyzed by Bridge, the process has added $382 million to Wayne County’s general fund since 2012 and helped the county recover from a near financial emergency.

Information about the profit of the foreclosure process prompted WDET talk show host Stephen Henderson to ask Wayne County Executive Warren Evans a tough question in an interview on Detroit Today last year.

“Is that an incentive to keep things the way they are with tax foreclosures?” Henderson asked Evans. “If you didn’t have that money, the financial strain would be worse… is that one of the reasons that the treasurer doesn’t entertain a different way?”

“No, no question,” Evans responded. “That would be blood money. There’s no doubt that the revenue is helpful but anybody who would want to keep the status quo in order to bring in the revenue shouldn’t be in government.”

“It would be a pretty dark calculation!” exclaimed Henderson.

“Yes,” Evans agreed.

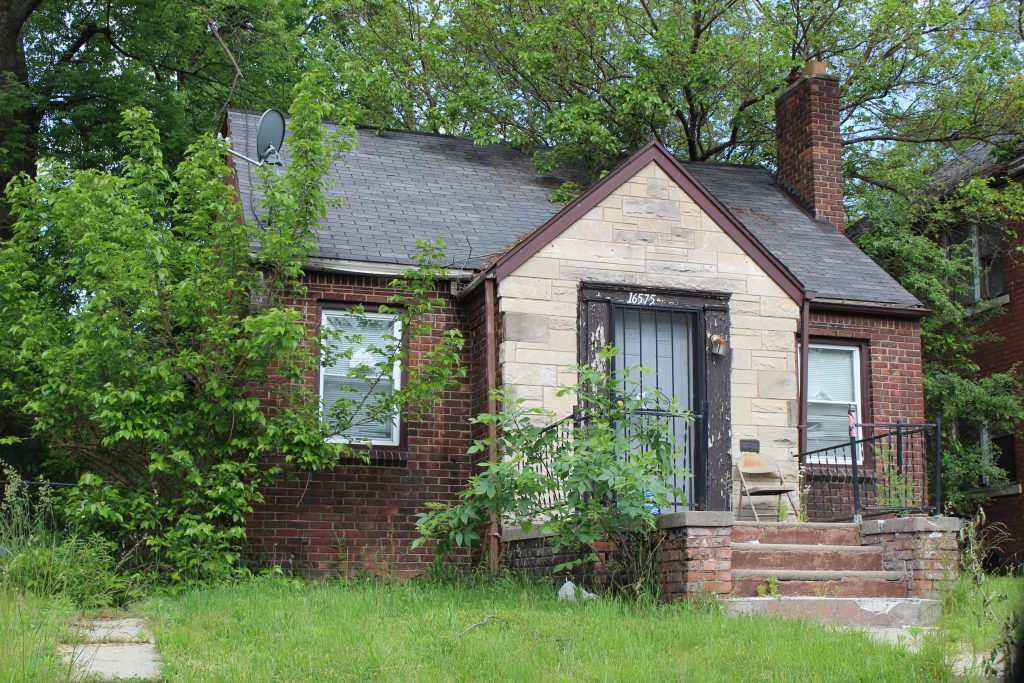

Yet the head of a Detroit data company is convinced that this is a calculation that is indeed being made. LOVELAND Technologies CEO Jerry Paffendorf says the state’s tax foreclosure process is bad business for Detroit because it creates blight and may be slowing down Detroit’s population growth. To illustrate his point, we’ve headed to a section of the Fitzgerald neighborhood on Detroit’s westside. The city announced earlier this year that, as part of a foundation-funded demonstration project, every public parcel in a quarter square mile area will be revitalized here.

Paffendorf pulls out his smart phone revealing a map with black, blue, pink and red parcels.

“Basically anything that’s colored in the app right here is a property that’s been in foreclosure in Fitzgerald since 2002,” he says.

According to his data, there are roughly 4,000 properties in this neighborhood and about half of them have gone through tax foreclosure.

“They went through foreclosure recently,” Paffendorf is pointing to a house out the left window. “And I don’t think there’s any rebuilding that one.”

The house is burned down to the point where we can see through its front porch to the back yard. Most houses here are not quite so bad. Some nearby ones that had been tax-foreclosed still look like people live in them. Others have boards on the windows with little red painted flowers. According to LOVELAND’s data, nearly one in six occupied homes in the city that went to the auction in 2014 were visibly vacant the following year. That’s one roughly one thousand homes that became blight and safety concerns as a result of the tax foreclosure process.

“If the point of the policy was to have a big enough stick to get people to pay their taxes, then I think these days you have to just look at it and see a failed policy because it’s all stick and no carrot,” Paffendorf says while we cruise around Fitzgerald.

“Well, but if they pay their taxes they can stay in their home I guess,” I counter.

His response: “If they don’t pay their taxes then the city and the county get to tear itself apart.”

An Answer?

Paffendorf, who ran unsuccessfully to fill the county’s vacant Treasurer seat in the interim after Wojtowicz retired, has a plan. It involves utilizing nonprofits to give people in occupied homes facing tax foreclosure the opportunity to rent, buy, or get relocation assistance rather than just having them evicted.

Phil Cavanagh, director of special projects for the Wayne County treasurer, says his office understands displacing residents is not ideal.

“Everybody sees the value in keeping someone in their homes it’s just you have to keep in perspective that 95 percent of the people pay their taxes on time so it’s got to be fair, also,” Cavanagh says.

In accordance with the law, the county last November notified houses facing foreclosure by delivering information inside orange baggies to their doorsteps. The county Treasurer’s office also put up billboards and paid for TV commercials. Cavanagh says the office is adding to the efforts of nonprofits like United Community Housing Coalition by funding a campaign to knock on 6,200 doors to alert residents of their options.

“This is just those people who’ve made no contact with our office. We just want to make a last ditch effort to try to get them to respond,” he says.

Still, the county predicts 4,500 occupied homes will be listed for sale at the next online auction in September.

As for Annie Perry, she was able to successfully sign up for a payment plan. This means the county will collect some money from her, her house is safe from tax-foreclosure for at least another year, and her neighbors won’t have to wait and see what happens to the house come fall.

Bridge Magazine Reporters Joel Kurth and Mike Wilkinson contributed to this piece as part of WDET’s work with the Detroit Journalism Cooperative.