CuriosiD: Was there busing in Detroit in the early 1960’s?

Sascha Raiyn June 20, 2017There was, and battles in Detroit shaped busing throughout the U.S.

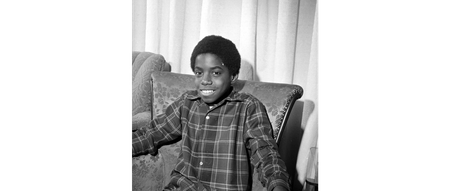

Listener Cheryl Pernell was intereted in examples of busing in Detroit Public Schools around 1963. Pernell was bused to Dossin Elementary for the 1st through 7th grades, instead of going to Ruthruff in her neighborhood.

But Ruthruff and Dossin weren’t the only or the biggest examples of early busing within the district.

Central Michigan University political science professor Joyce Baugh said the push for integration in Detroit schools started with a fragile coalition of African American, labor and liberal forces in the late 1940s.

“In 1949, they were able to get two of their candidates elected to the school board,” Baugh said. “One of them was Dr. Remus Robinson, who was the first Black elected official in the city.”

Over the next decade, the district made some progress in increasing Black teachers and support staff.

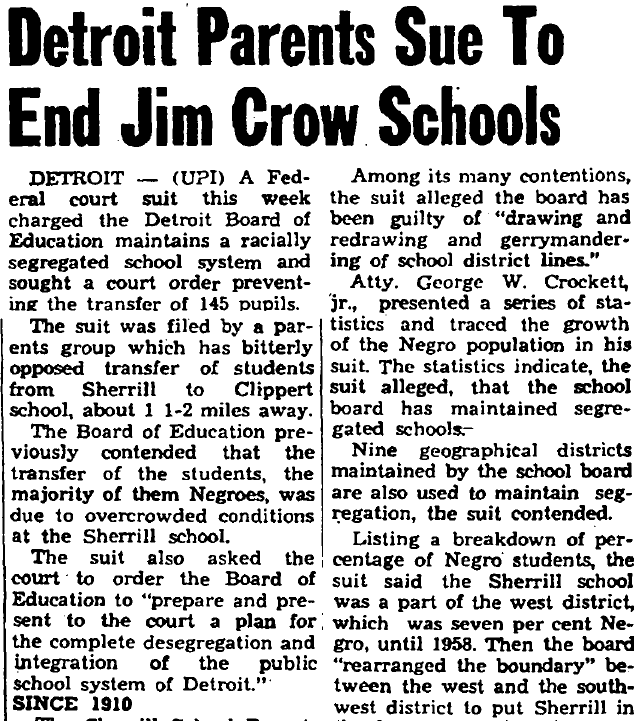

“But the school board still really was dragging its feet on the issue of segregation,” Baugh said. “Especially on gerrymandering the attendance boundaries.”

The district drew lines around black and white neighborhoods and used those boundaries to create the feeder paths students would follow from elementary school to middle school to high school. When the demographics of a neighborhood changed, the attendance boundaries changed as well. So, schools and neighborhoods stayed segregated.

Meanwhile, baby boomers were bursting out of the existing schools in the city. Overcrowding, then, provided an opportunity for the district to make some progress on integration. In October 1960, the district introduced a plan to bus 300 black students from Brady and MsKerrow elementary schools in the central district to Guest, Monnier and Noble in northwest Detroit neighborhoods.

“The argument was that they were refusing to build any schools in the black areas of town so they could use the overcrowding of those schools to force integration on the white schools,” — Joyce Baugh, Central Michigan University

Unhappy parents formed the Northwest Parent Action Committee in response. They boycotted the schools – keeping more than 1,200 students out at its peak. Organizers packed a school board meeting with two thousand parents.

“The argument was that they were refusing to build any schools in the black areas of town so they could use the overcrowding of those schools to force integration on the white schools,” Baugh said.

Then-Superintendent Samuel Brownell argued that children had been bused to these particular schools for years. What had changed was the race of the students.

The Detroit school board didn’t back down. After about a month, the boycott ended. But black parents weren’t happy. The students were segregated within the schools.

In 1962, another chapter in Detroit’s integration efforts began. An interracial parent group sued the school board saying it had redrawn attendance boundaries to keep black students from attending Mackenzie High School. The suit outlined a list of district practices the group said were blatantly discriminatory and designed to segregate. The parents dropped the suit in 1964 after a new “pro-integration” school board was elected.

That’s Dan Golodner. He’s the archivist for the American Federation of Teachers at Wayne State University’s Walter Reuther Library.

“The school board became a black labor unity school board mid-sixties,” said Dan Golodner, archivist for the American Federation of Teachers at Wayne State University’s Walter Reuther Library. “Everybody thought this was gonna be the new school board that would make the huge changes needed.”

The board ran on a platform of building schools, creating equitable programs and solving integration. It was elected when – for the first time – white children were a minority in Detroit’s schools.

The board did present a proposal to integrate 11 of the city’s 22 high schools, but not until the spring of 1970. It was not well received.

The Michigan legislature voted to repeal the plan and then-Governor Milliken signed the repeal. The NAACP sued the governor, the state and the school district in a case that showed how housing discrimination and school segregation were aligned. A federal court ruled in 1971 that in order to end school segregation, an integration plan would have to include five counties. As white people continued to leave the city, it would have to include the suburbs.

The U.S. Supreme Court overturned that ruling saying integration efforts should only be district-wide – only in Detroit. Justice Thurgood Marshall wrote a dissent:

“A Detroit only plan simply has no hope of achieving actual desegregation. Under such a plan white and negro students will not go to school together instead negro children will continue to attend all negro schools. The very evil Brown was aimed at would not be cured but will be perpetuated.”

“For these reasons, the Detroit only plan simply has no hope of achieving actual desegregation.

Under such a plan white and Negro students will not go to school together, instead, Negro children will continue to attend all-Negro schools.

The very evil that Brown was aimed at will not be cured, but will be perpetuated.

The rights at issue in this case are too fundamental to be abridged on grounds as superficial as those relied on by the majority opinion today.” — dissenting opinion from Justice Thurgood Marshall

Milliken v. Bradley – as the case is known – established that school districts could not have explicit policies that segregate students, but when segregation was a result of where people “chose” to live the district could not be held responsible. The Supreme Court rejected arguments that housing discrimination kept African American families from choosing where they lived.

This ruling would shape busing efforts across the country.

Listen to the U.S. Supreme Court Opinion Announcement

ASK YOUR QUESTION

ABOUT DETROIT OR THE REGION

WDET’s CuriosiD is sponsored by the Michigan Science Center.