Information Disparity: Local Governments Show Wide Variety in Access to Information

A WDET analysis helps you understand how to get records and documents from your municipality.

If you want to find out what contracts your local government has with private companies or environmental assessments of community sites, for example, you have a Michigan law on your side: The Freedom of Information Act.

The 40-year-old measure requires local governments – as well as state agencies, school districts, public universities and other public bodies – to make records available. That means if you want to see, for example, construction permits issued for a house you’re considering buying, you can ask the municipality to let you see them or to make copies for you.

“It gives citizens what, frankly, we always thought we had which is a right of access to know what’s going on in government,” says Jane Briggs-Bunting, founding president and current board member of the Michigan Coalition for Open Government.

But what information each community shares online about the law – popularly known as FOIA – isn’t the same in southeast Michigan, nor is the process for using it. The law does not require that municipalities put FOIA information online, but open government advocates say it’s what’s expected by today’s citizens of the digital world.

WHAT IS THE GOVERNMENT TELLING YOU?

A WDET investigation finds that municipalities in metro Detroit are not always letting the public know that the FOIA law is a tool that’s available, and that there are big differences between how municipal websites present information to people who may want to obtain it.

And when FOIA is a link or page on a website, transparency advocates say, it is not always presented in the most user-friendly way.

WDET, with the help of two students from Wayne State University’s School of Information Sciences, analyzed the 129 local government websites in Macomb, Oakland and Wayne counties to see how accessible FOIA information is for anyone visiting those sites.

For a map of communities with links to file a FOIA request, click HERE.

There’s a wide variety in what’s available from the townships, villages and cities:

- Less than a quarter of the governments have direct links on their homepages that will take you to forms you can fill out and send to the municipality to make your FOIA request. To find the information, you either need to know to search “FOIA” or “Freedom of Information” or to click through a series of dropdown menus, often through the clerk’s office.

- Three municipalities – Ortonville, Lake Angelus and Leonard – have no FOIA information online at all. Oxford added a FOIA link and information to the site after WDET inquired why it wasn’t there. The other municipalities did not return telephone messages.

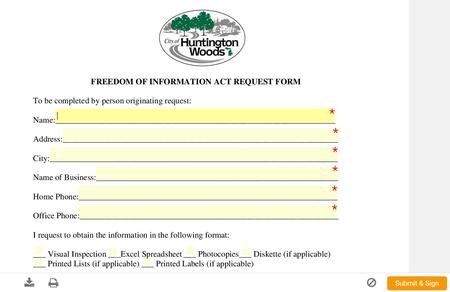

- Just eight of the local governments allow you to e-file your request directly from the municipality’s website.

- WDET used each of the eight e-file systems to request similar information, asking for the five previous FOIA requests made. Three municipalities – Canton, Lenox, and Shelby townships – e-mailed information to WDET for free, sometimes within hours of the request being made. The city of Plymouth charged 12 cents for the requests to the police department and $3.66 for requests to other city departments, which had to be paid before they would share the information. Others went unanswered before publishing and airing this report.

- Of the 31 sites that mention FOIA on their homepages, none use “user-friendly” language, according to Dave Cuillier, director of the University of Arizona School of Journalism and author of the book “The Art of Access: Strategies for Acquiring Public Records.”

“It should be a lot better. It should be simple to acquire whatever you want, and it should be pro-active,” he says.

He suggests instead of “FOIA” on the homepage – a term people may not be familiar with – that municipalities use phrases like “How To Request Records” or “Want Information About Your City? Click here.”

THE HISTORY

Michigan’s FOIA law dates back to 1976 when then- Rep. Perry Bullard (D-Ann Arbor) introduced it and lobbied for it.

“Perry considered himself a reformer and a progressive and was very much a supporter of open government and thought democracy worked much better when the public can be informed and that we have opportunity to get documents regarding the work of our government,” says Dave Monforton, now an Ann Arbor realtor who previously work on Bullard’s staff.

The FOIA law was passed by the Legislature, signed by then-Gov. William Milliken, and enacted in 1977. It became the subject of numerous state Attorney General opinions including one in 1986 that exempted the governor, lieutenant governor and the Legislature.

In the wake of the Flint water crisis, after questions about how the governor’s office handled the situation, bills introduced to expand FOIA to the governor and the Legislature have passed the House but not made it out of Senate committee.

“This is a terrible weakness,” Briggs-Bunting says. “Here are the people who are making the laws about what public bodies have to disclose, what the cities have to disclose, what the mayors have to disclose, what the school board has to disclose, what police have to disclose and yet holds itself about the law they made. It’s really unconscionable.”

Meanwhile, local governments continue to respond to requests and adapt to changing technology, says Catherine Mullhaupt, staff attorney with the Michigan Township Association.

Some local governments are working to post more information online, Mulhaupt says, because having the information available can negate the need for a FOIA request.

“It’s not that everyone who sends you a FOIA is an angry person, but you have to be conscious that this is a customer service,” she says. “Not only is it required by law, but there’s a customer service aspect.”

In fact, Michigan’s 2015 revisions to the FOIA law allow governments to point a requestor to where the information is online in lieu of providing a specific document. But Mullhaupt says some of the state’s townships have budgets less than $50,000 leaving little funding for technology.

Acknowledging that smaller townships or villages do have legitimate budget and staffing issues that prevent them from building out their websites with a lot of FOIA information or tools, Cuillier also says that providing for e-filing FOIA requests can save a municipality staff time and expense. In his research he’s found that the relative anonymity of an e-mailed FOIA request can prevent some of the tense interactions that can occur between the person making the request and a government employee.

“Certainly it’s easier if it’s done electronically and more efficient and that’s what we should move to,” Cuillier says. “But there’s always going to be that kind of friction and adversarial-ness in the system no matter what, particularly with requests that have anything to do with politics or sensitivity in any way.”

Attorney Toby Sorios, based in Farmington, has filed hundreds of requests for information in his legal career and prefers the e-filing systems.

“You always want to go online and try and do it,” he says. “Everything – anything paper – is going digital. … You’re getting more information, and you’re getting it faster.”

Canton is one of the eight metro Detroit communities where e-filing a FOIA request is available. Clerk Michael Siegrist says the ability to e-file from the township’s website is part of an effort to serve a wide audience.

“When we pivoted away from .pdf as an electronic format for FOIA submissions, we pivoted into a form that is compliant with updates to the Americans with Disability Act, that’s very user-friendly, and provide ease and comprehension for your average resident,” Siegrist says.

Using the online form instead of filling in a document, saving it, and then sending it saves the requestor time.

“It also makes it easier for us as well,” Siegrist says. “It kind of takes out some of the guess work, and it creates a uniform system for tracking.”

WDET Multimedia Producer Melissa Mason, WDET Intern Erin Andrews and Wayne State University School of Information Sciences graduate students Joseph Gross and Heather Levrant contributed to this report.