CuriosiD: How Did Detroit Become a Center for Arabs in the United States?

Shelby Jouppi August 8, 2017A 14-year-old listener from Northville learns how faith and family helped shape one of Detroit’s best-known communities.

WDET listener Priya Ganji has a diverse group of friends of Arab heritage, and she’s noticed their family, religious and cultural traditions are sometimes different from her own and other Americans’. So the 14-year-old asked WDET this question:

“How did the Arab community grow to be what it is today in Detroit?”

THE SHORT ANSWER

The Arab-American community in Detroit began with a small group of Syrian and Lebanese merchants who immigrated in the late 1800s. Many left their lives as peasants in the rural Middle East for the rapidly industrializing West, sometimes passing through Ellis Island on their way to Detroit.

The community’s growth over the last century can be traced through what some call an unfortunate combination of events involving war and a lack of economic opportunities in the Arab World and relative peace and plentiful jobs in the United States.

The first enclave of Syrian, Lebanese and Yemeni immigrants in metro Detroit thrived in the early 20th century, building small businesses and places of faith, and the Arab population grew steadily over the next 100 years. Experts and Arab-American leaders say today’s immigrants know they will find opportunity and an established community in Detroit, which will support their families and faith.

According to the U.S. Census, the Arab-American population in metro Detroit is now one of the largest in the country.

ONE OF THE OLDEST ARAB-AMERICAN FAMILIES IN DETROIT

Najah Bazzy’s grandfather immigrated to Detroit from Lebanon in 1885. He was one of a small group of Arabs to first settle in the Detroit area. Others found homes in city centers throughout the U.S.

“They were merchants selling fruits and vegetables on trucks,” Bazzy says.

Her grandfather grew up in rural southern Lebanon with little access to the city of Beirut. The family was poor, and Bazzy says the children did not have shoes and were laborers by the age of nine or 10.

“(My grandfather) wanted a different life for himself and his children,” she says.

The story is similar to many for Arabs and other immigrant groups: men leaving behind impoverished lives to pursue opportunity in the United States. A couple of decades later, a large group of Arab immigrants would make its way to Detroit, which marked the first major period in the community’s growth.

PERIOD ONE

The $5 Dollar Work Day

Detroit’s automotive industry was a magnet and drew thousands of people who were in search of the well-paying jobs. This is a well-known story, and Arab-Americans were part of it.

Sally Howell, director for the Center of Arab American Studies at University of Michigan-Dearborn, says Henry Ford’s $5 work day, which he introduced in 1914, really triggered the influx.

People from Arab countries like Syria, Lebanon and Yemen, were among the flood of newcomers as Detroit’s population more than tripled from 1910 to 1930, rising from 465,766 to nearly 1.6 million, according to the U.S. Census.

The decline of the Ottoman Empire played a big role in ushering Arabs to the West, Howell says. In Lebanon, for example, the economy basically collapsed. For countryside dwellers, like Bazzy’s grandfather, resources were scarce.

Men needed jobs, and Detroit had plenty of them. This first influx of immigrants settled in Highland Park near Ford’s plant, which made the Model T and was the home of the first moving assembly line. Across the street from the factory, a group of Arab, South Asian and European Muslims opened the first purpose-built mosque in the United States in 1921.

Not all Arabs are Muslims, though. In fact, most of the first Arabs to come to the U.S. were Christians who opened Orthodox and Maronite churches around the city. Some of these congregations exist today.

These places of faith provided central support systems in Detroit and would become a big draw for new Arab immigrants, especially families who wanted religious institutions to help guide their children’s upbringing. Mosques and churches became social networks for newly arrived people unfamiliar with American language and culture.

Howell says when Ford opened his River Rouge complex in Dearborn in the late 1920s, many Arab-Americans followed him there and settled in the South End of the city. They opened businesses, grocery stores and restaurants.

To this day, Dearborn’s South End is a diverse enclave of second- and third-generation immigrant families, many of whom are from Lebanon, Syria or Yemen.

PERIOD TWO

The 1965 Immigration Act

The second major event affecting Detroit’s Arab-American community begins with a change in U.S. immigration policy. In the 1920s, the federal government effectively banned Arabs and Asians from settling in the U.S.

The government did not lift this ban until some 40 years later when Congress passed the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, promising the U.S. would accept immigrants of all nationalities on about an equal basis.

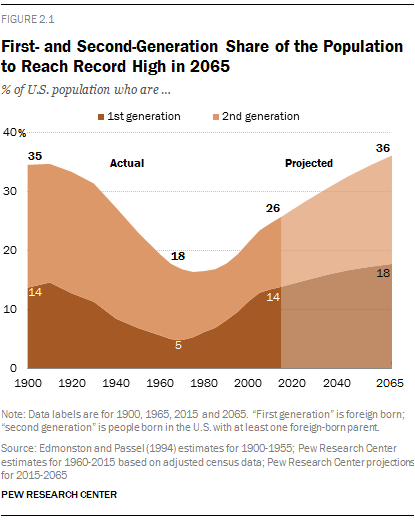

It had a dramatic effect on the country’s demographic makeup. In the decades since, immigrants have almost tripled in their share of the American population, from constituting roughly 5 to 14 percent, according to the Pew Research Center.

This change in policy, and the conflict and poverty in many parts of the Arab World, served as the ingredients for more significant growth Detroit’s Arab community. North and South Yemen struggled violently for decades before uniting as the “Republic of Yemen” in 1990, and now civil war continues.

In 1975, a complex, 15-year civil war broke out in Lebanon. In the 1970s and 80s, an influx of immigrants from both countries settled in the South End of Dearborn among the established community there.

But a group of Arab-American Vietnam veterans and activists saw that these immigrants desperately needed help finding jobs, healthcare and learning English. The group created the Arab Community Center for Economic and Social Services, or ACCESS.

“I think it’s unfortunate that immigration to Detroit from the Arab World is always triggered by unrest,” says Hassan Jaber, the CEO of ACCESS, which is now one of the nation’s largest Arab-American organizations.

Jaber immigrated to the United States from Lebanon at the beginning of the civil war. He was 18. In the years since then, he’s witnessed many people like him come to the Detroit area for similar reasons.

“So every war we see an influx of immigration. We’ve seen it in 1975 with the Lebanese Civil War. We’ve seen it in the 80s because of the Iraqi War. We’ve seen it in the 90s because of the Iraqi War, and unfortunately we’re seeing it now with the civil war in Yemen and the Syrian conflict,” he says.

PERIOD THREE

The First Gulf War to Today

The third major period in Arab immigration began right around the first Gulf War in the early 1990s. Iraqi Muslims and Chaldean Christians fled to the United States, and many made their way to metro Detroit.

A couple of decades later, the Tunisian revolution of 2011 began a ripple effect of violent and nonviolent protests, revolution, and in some cases civil war across North Africa and the Middle East. This was called the Arab Spring. Conflict lingers today in Iraq, Syria and Yemen, and across North Africa.

Jaber says the Arab-American population here has doubled since the 1980s. According to the Arab-American Institute, Michigan’s Arab-American population was around 350,000 in 2012.

In recent years ACCESS has seen refugees who originally settled in other parts of the United States make a second migration to suburban Detroit – like Sterling Heights or Warren.

WHY METRO DETROIT?

There are a few key reasons why new Arab immigrants continue to be attracted to the Detroit area. Many people have family members or former neighbors who moved here, Jaber says.

Just like generations before them, a significant draw for new Arab immigrants to settle in Detroit is the strong network of churches, mosques and service organizations here that are able to support their families and faith.

“There are roughly around 11,000 small businesses [in Southeast Michigan] owned by Arab Americans employing 170,000 people,” says Jaber. “So that by itself is almost a subeconomy that [new immigrants] can have opportunities for jobs and making a living here in Michigan.”

The Trump Administration’s travel ban and new immigration policy, Jaber says, are creating an uncertain future, making it difficult for those hoping to settle in metro Detroit during the next few years.

But amid the uncertainty, Jaber thinks Detroit can serve as a model for the nation.

“I think what I’m hoping to do is take this experience of positive engagement that we’ve seen here in the Detroit area of Arab Americans in civic life and … help Arab Americans have a voice on the national level,” says Jaber.

ABOUT THE LISTENER

Priya Ganji is a high school sophomore from Northville who aspires to become a doctor.

Her diverse group of friends inspired her to ask her question.

“I have a lot of friends who come from that part of the world,” she says. “I noticed that they always have family around for a lot of festivals and gatherings. That [question] was always in the back of my mind.”

ASK YOUR QUESTION

ABOUT DETROIT OR THE REGION

WDET’s CuriosiD is sponsored by the Michigan Science Center.