CuriosiD: Why Does Michigan Avenue Have Brick Pavers?

Bre'Anna Tinsley July 3, 2018A listener asks why there is a stretch of brick road in Corktown.

In this installment of CuriosiD, listener Dan Lombardo asks:

I was wondering why there are brick pavers at Michigan and Trumbull and if they are original or if they are something they redo every now and then.

-Dan Lombardo

The Short Answer

The Good Roads Movement in the 1870s started by bicyclists pushed for better streets for them to ride on. Previously roads were made of wood, gravel and dirt, which was difficult to travel on when it rained or snowed. City planners tried multiple solutions for improving roads, including granite, asphalt and brick. Michigan Avenue and Grand River Avenue were among the first in Detroit to get brick pavers. Today, Corktown residents have fought to keep the pavers on Michigan Avenue maintain the ‘historic feel’ of the neighborhood.

The Historic Road

Michigan Avenue was first placed by former governor Lewis Cass and Father Gabriel Richard in 1807 as a military road to connect Detroit to Fort Dearborn. Cass and Richard received $3,000 from the federal government to pave the road with oak logs and covered in dirt. Most roads during that time were paved in the same manner or with gravel.

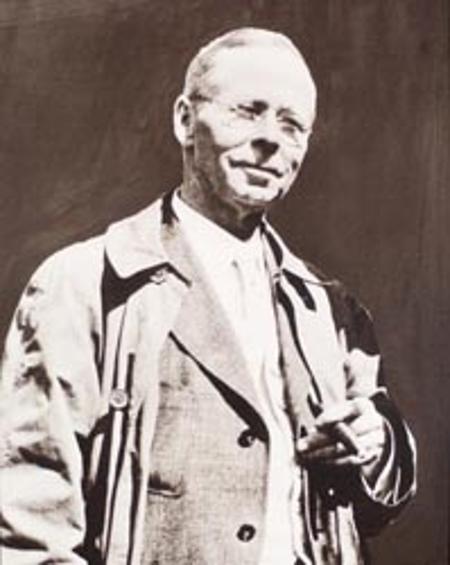

Horatio “Good Roads” Earle

Most people may think that automobiles created the demand for better roads. However, automobiles hadn’t become popular until the turn of the 20th century. In fact, it was in the 1890s when bicycling became very popular that people started advocating hard for paved streets.

Back in the mid-1800s, inner cities had more paved surfaces than connecting roads. Those who traveled by horse or carriage could easily stroll down the road, even in muddy weather. However, once bicyclists became more popular, the need for paved roads increased.

“When bicyclists came along they wanted to ride their bikes to different cities,” says Todd Scott, executive director of Detroit Greenways Coalition, a non-profit that focuses on creating greenways and green spaces in the city. “And they went to the countryside and the roads were in horrific shape. And so, bicyclists began the Good Roads Movement across the United States to take these roads and build them properly.”

One of those advocators was Horatio Earle. Earle was a Detroiter and president of the League of American Wheelman, a bicyclist group who were among the first to promote bike paths alongside public highways. The good roads movements spread across the country.

Brick pavers were laid on Michigan Avenue the 1890s. Michigan Avenue and Grand River were among the first to get the brick pavers in Detroit.

During his road improvement efforts, Earle gained a state senate seat and pushed for the creation of a state highway department, which eventually became the Michigan Department of Transportation – or MDOT.

Under Earle’s administration, along with Edward Hines, former chairman of the Wayne County Road Commission, the first mile of concrete road in the country was paved on Woodward Avenue.

Brick roads no longer practical

Brick roads were just one of the solutions tried to help better the roads under Earle reign.

“They paved them in different ways,” says historian Joel Stone from the Detroit Historical Society. “Michigan Avenue and Grand River were both paved in bricks. While Gratiot, was paved in ground granite and Woodward Avenue and Jefferson were paved in asphalt.”

Stone says the bricks seemed to be a good solution and were easy to manage at the time.

“It was fairly easy to put down and pretty easy to repair. You pull the bricks up if you had to get to a sewer and you can put the bricks back down the way they had come up.”

Today, that’s not the case. Rita Screws, manager at MDOT’s Detroit Transportation Service Center, says maintaining the brick road today is a lot more difficult.

“The art of building brick roads has long since passed.” Screws says. “With a road as old as Michigan, we have a lot of failures. It becomes costly to repair them because we have to contract out to do that and those people who have the skills to do that are not as readily available.”

In fact, she says, the bricks replaced in the parking lanes along Woodward during the construction of the QLine, the design was rejected eight times.

MDOT has been working to remove the brick. But, Corktown residents have fought to keep them in place to preserve the historic aesthetics of the neighborhood. The department instead suggested replacing the brick with stamped concrete that still resembled brick.

“The community kind of came together on that and agreed to it,” says Tim McKay, a Corktown resident and president of Corktown Experience. “Because mostly we were getting tired of the condition of Michigan Avenue. But it was all about maintaining the atmosphere.”

That agreement was made right before the recession and has since been put on hold until funding can be found.

Today in Corktown the bricks still lay. Michigan Avenue in its entirety is recorded as a historical site with the State Historic Preservation Office.

Not the only brick paved road

Grand River was also paved with but has since been covered. As well as other streets in Detroit.

Marlborough Street between Jefferson and Essex on Detroit’s far east side is paved in brick.

“I also know, and people that drive around Detroit will see this,” says Joel Stone, “when the asphalt skin comes off of many of our streets, there are still a lot of bricks streets in the city of Detroit.”

About the listener

Dan Lombardo is an electrician from Waterford. His grandfather moved to Corktown in 1920. His dad was born later on Porter street in the neighborhood. He says his dad would always say he was born “in the shadow of Tiger Stadium.”

“I always thought he knew a lot about the area,” Dan says. “I would ask him why are there brick pavers in the street, and he says ‘I don’t know they’ve always been there.’ I figured if he didn’t know, I don’t know if anybody would ever know.”