This is A Drill: Poll Worker Training in Detroit

A state report found fault with Detroit poll workers in 2016. Here’s a glimpse into training aimed at improvements.

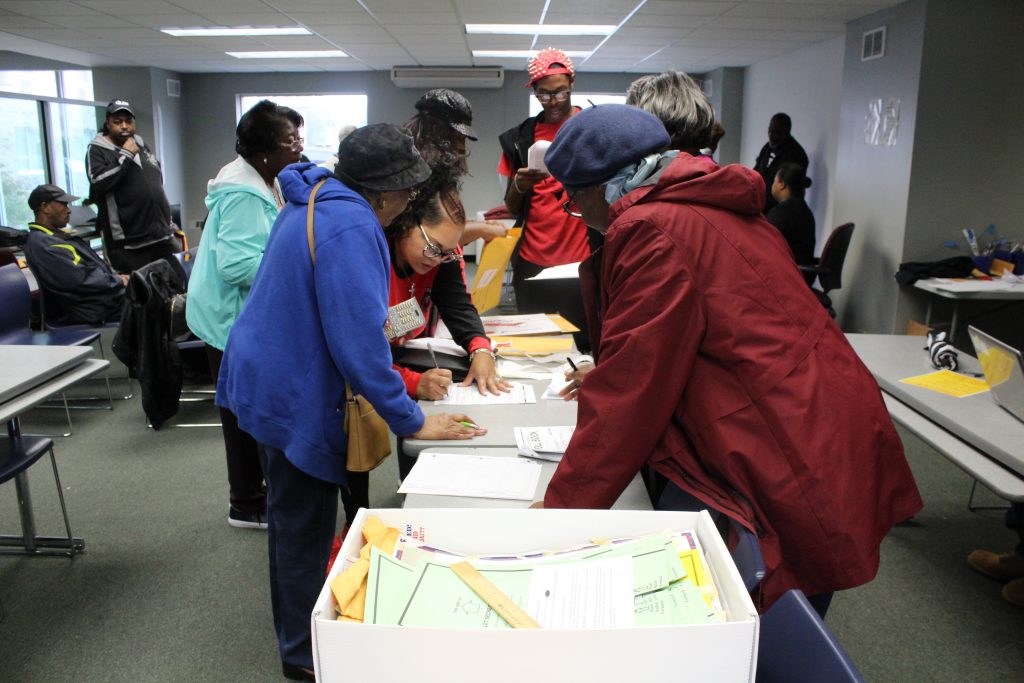

It was standing room-only in the old administration building at Wayne County Community College’s Northwest Campus. Forty people were there at 9 a.m. on a Saturday for poll worker training.

This three-hour class is mandatory for residents who want to work Detroit’s Nov. 7 election and earn up to $275 for the day.

Early in the session, trainer Darren Craddieth divided the group into four mock precincts.

“This is what’s going to happen,” Craddieth said. “First we’re going to go through opening. So, you’re going to have 15 minutes to open up your precinct, OK?”

The trainees sprang into action. Briefcases opened and became voting booths. Access codes were entered into ballot counters. A small American flag in a plastic stand was placed on a table “just so.”

These Detroit training sessions weren’t always so hands on. The change was put into motion after the presidential election last year when the Green Party filed for recounts in Wisconsin, Michigan, and Pennsylvania to make sure that elections hadn’t been hacked and that votes were counted accurately.

Michigan began its recount but a federal judge stopped the effort before it could be completed. But not before some shocking election errors were discovered in precincts across the state, and in 136 of Detroit’s 662 precincts in the 2016 election.

“There was a significant mismatch in those precincts between the number of recorded voters and the number of ballots that were found and maintained after the election,” said Fred Woodhams, spokesperson for the Michigan Secretary of State’s office, which runs the Bureau of Elections. The inconsistencies found during the recount led the bureau to launch a statewide audit of the election process.

“What we found is that there is a significant amount of human error that occurred in those precincts that caused that mismatch,” said Woodhams.

In Detroit, there were errors found on the laptops that kept track of voters. In some cases, counted ballots were not sealed in official containers, meaning they couldn’t be recounted. Plus, there were issues with provisional ballots, which are given out to voters when it seems they’ve shown up at the wrong polling location.

To address these issues, the state made recommendations for the Detroit Election Commission.

Learning By Doing

At the Detroit training, some of those recommendations were put into action.

The four mock precincts didn’t know it yet, but the trainer, Craddieth, was about to show them how to correctly process a provisional ballot.

“So, our first voter, is Mr. Levi Daniels,” Craddieth said.

A trainee playing Mr. Daniels handed a small piece of paper with a name and address on it to the trainee playing an application inspector.

“Next we want to search Levi Daniels in the computer,” he said, before hushing the group.

Turns out Mr. Daniels could not be found in the system. That meant his ballot would have to be set aside in a special provisional envelope.

“The reason why we’re going through this scenario first is because this is the scenario that we see that always make people not get a perfect precinct,” said Craddieth.

He ran through a handful of scenarios like this: what to do when someone doesn’t have an ID, or if the address on the ID doesn’t match the address in the system. He also showed the trainees how to use a special voter machine for people with disabilities.

Not As Easy As It Seems

Being a poll worker is complicated. And there are only a few election days a year for workers to get on-the-job experience. Many here agree with the state’s audit findings that lack of proper training led to issues with Detroit’s general election last year.

But some also cite problems that go beyond what can be covered in a classroom.

The voters themselves can throw things off, said David Robinson, who has worked elections in Detroit for three years.

“I seen people in there dancing and arguing,” he said. “I’ve seen people come in there take their clothes off and sing around, dance around, run back out real quick.”

Tiffany Lee, also a three-year-veteran, said last year she and her fellow precinct workers showed up on time, but still started off behind schedule.

“They was late opening up the building so we were … almost 30 to 45 minutes late opening up the building,” she said.

Carolyn McGhee, a certified public accountant, blamed equipment failure, specifically the tabulator machines

“Every two hours, I kid you not, our machines went down,” she said. “At the end of the night we had to put each one of those ballots in those machines so they could be counted.”

Those machines can be problematic, said Woodhams, the state spokesman.

“Certainly there were a few tabulators that jammed in Detroit – that happened across the state,” he said. “That was not the cause of the vast majority of the precincts not being able to be recounted in Detroit.”

Nonetheless, Woodhams said, it was time to purchase new voting equipment. That’s why the Secretary of State, the Governor’s office and the Michigan Legislature provided funding for all voting precincts in the state to get new machines. Detroit debuted its machines during the August primary.

Only A Drill

As the end of the three-hour session neared, trainees were working to close up their mock precincts. It was during this time that supervisor-in-training Walter Hobson gasped, “Ohhh!”

He had spotted a stack of ballots that were about to be left behind, unsealed.

“Hey y’all, we skipped a step,” Hobson yelled to his mock precinct. “When they declare that polls are closed, you check your bins first. We forgot to check our bins.”

This was one of the problems discovered during the state’s audit of Detroit. Ballots like these were counted during the election, but because they were left unsealed, state law prohibited them from being included in the recount.

Luckily, this time, it was just a drill.

These trainees, and hundreds of other poll workers, will be on duty for Detroit’s municipal election on Nov. 7. If their precincts do everything correctly, the workers there will each get a $25 bonus.

Information on becoming an election day worker in Detroit can be found here.