CuriosiD: What Happens to the Stuff I Recycle?

Kim Hunter wants to know how his curbside recycling gets sorted and what happens to the money.

In this episode of CuriosiD, listener Kim Hunter asks …

What happens to the stuff I recycle with the City of Detroit (curbside recycling)? Where and how is it sorted? Is it sold, and what happens to the money?

// Kim Hunter, Detroit

The Short Answer

It goes to a facility where machines and people work to sort through everything you give them. The facility creates large bales of these materials sorted by type – papers, plastics, metal, aluminum, and more. Those bales are then sold and further processed to become new water bottles, pop cans, toothbrushes and kayaks. Sometimes, however, the material is sent to a landfill.

Where It Goes

All curbside recycling makes its way to something called a materials rescue facility (MRF). Here, a handful of people and machines do their best to roughly sort your recyclables by type and remove what is not recyclable.

Pretty much everything Detroiters put in their curbside recycling carts ends up at ReCommunity Recycling, in Southfield.

After the material is roughly sorted by type and compressed into bales, the bales are sold to individual recycling facilities that further process the material. The companies do things like smelt aluminum, shred and pulp paper – basically get the materials ready to be used in manufacturing.

For example, Transpol Recycling in Hamtramck buys bales of bulky rigid plastics – laundry baskets, kitty litter tubs, etc – from ReCommunity. They sort the plastic further, shred it, and granulate it into small pellets.

From here, the refined materials are sold to be manufactured into new products.

Jim Finn, co-owner and manager at Transpol, says their plastic pellets go on to become things like toothbrushes, totes, and kayaks.

Recycled materials from the US will sometimes make it to the other side of the globe. China, for example, is one of the largest buyers of recovered materials.

How It’s Sorted

This part looks different depending on which method of curbside recycling your municipality uses. Some employ a multi-stream method – where users have to sort recyclables by type before putting them out on the curb. Others, like Detroit, use the single-stream method. It’s the easiest for the user – just put everything in one big bin.

ReCommunity’s facility in Southfield is a single-stream facility. All recyclables – milk jugs, pop cans, yogurt cups and more are heaped into one massive pile.

Mike Csapo, General Manager of Resource Recovery and Recycling Authority of Southwest Oakland County (RRRASOC), says this facility processes around 300 to 500 tons of material in a day.

The sorting process starts with the pile of mixed materials being fed to a hopper and dumped onto a conveyor belt. A couple men stand on either side, hauling large recyclables like scrap metal off the belt and removing “contaminants,” or non-recyclable material.

Csapo says things like plastic grocery bags, wire, VHS tape, and garden hoses get tangled in the sorting screens.

“During downtime, whether it’s lunch hour or break or in between shifts, people will have to physically get in there and remove those bags,” he says.

Csapo says this happens multiple times a day.

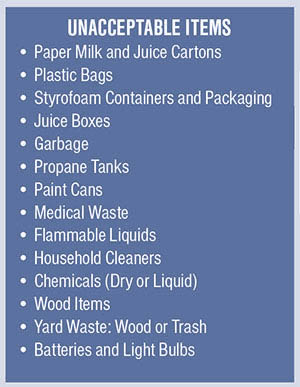

Wonder what’s not recyclable at ReCommunity and similar facilities? Click here >>

Throughout the system, a handful of machines sort material by type. A magnet pulls metal off the belt and drops it in a separate bin. An eddy current removes aluminum. “Optical sorters” use lasers to identify kinds of paper and plastic and jets of air to launch the material onto the appropriate conveyor belt.

“The [human] sorters are really the heart and soul of the operation,” Csapo says. “Those are the guys that are going to have to be on the front lines. They’re all full-time employees. … Everybody’s working five to seven days a week.”

These sorters are responsible for quality control. They remove non-recyclable materials, like forgotten dolls and the occasional dirty diaper. And they watch for items that may have made it to the wrong part of the system.

Once the material has been sorted by type, a baler tightly compresses it into a large cube. Those are then shipped off to market to places like Transpol Recycling in Hamtramck and Tabb Packaging in Dundee.

A Faulty, Fragile System

There are a few scenarios in which the stuff you recycle could get sent to a landfill.

First, and most obvious, if you put material that cannot be recycled at your MRF, it will inevitably be sorted out by hand and sent to a landfill.

Mike Csapo of RRRASOC says that “highly contaminated” or truck loads of material are rare but do occur. In that case, the entire load is sent directly to a landfill.

Csapo says ReCommunity’s Southfield facility sends approximately 10 percent of what it receives to landfills because the material is either not recyclable or it’s filled with debris, like food.

Thirdly, second step processors will do this if they receive bales are heavily contaminated.

Csapo says their operation mostly just covers its costs.

Jim Finn, manager and co-owner at Transpol Recycling, says, for tier two processors like his company, there is money to be made, but it doesn’t come easily.

“Nobody has any idea of what the realities are really like.” he says. “Plastic recycling is hard, dirty work and it’s hard to make money. Our margins are very small.”

“If petroleum goes down … another several dollars, it’s going to make things go from hard to maybe almost impossible. And plastic recycling would stop,” Finn says.

Finn says recycling is economically driven, and current market events could make plastic recycling slow to a halt.

Petroleum prices are falling. And plastic is made out of petroleum, which means as it gets cheaper so does the cost of making new plastics.

Finn says, the trend could make new plastic so much cheaper than recycled that there would be very little incentive for manufacturers to use recycled plastics.

“If petroleum goes down … another several dollars, it’s going to make things go from hard to maybe almost impossible. And plastic recycling would stop,” he says. “If I did not buy this particular kind of plastic [from ReCommunity], chances are very good it could just end up in a landfill.”

Recycle More, Recycle Right

Mike Csapo of ReCommunity says the best way to optimize the effectiveness of recycling is to not just recycle more often, but to recycle the right material.

If users blindly put non-recyclables in their bins, it causes significant problems for the facilities processing the material and could very well contaminate good, recyclable material. He says users should also make sure they rinse out their containers.

Check out the information graphics to the right for a list of what is and is NOT recyclable, according to the City of Detroit >>

Why Detroit Recycles: Let’s Burn Less Trash!

Curbside recycling in Detroit is only a couple of years old.

Zero Waste Detroit, a collective of Detroit-based environmental organizations, lobbied for the creation of the curbside recycling program in the city.

Galen Hardy, Community Outreach and Education Coordinator at Zero Waste Detroit, says the advent of the program has strong ties to activism against the city’s incinerator, where much of metro Detroit’s trash goes to be burned.

“They brought their forces together to start saying … ‘If we can’t shut the incinerator down, we want to definitely increase recycling, so then the more people recycle, the less that’s going to go in there,’” Hardy says.

Kim Hunter, who asked this question, is a lifelong Detroiter, poet and social justice advocate. (You may have even heard him as a music host on WDET in the 90s.)

One of Hunter’s first publicly performed poems was in protest of the building and operation of the Detroit incinerator.

Hunter says he had not realized the connection between the incinerator and Detroit’s curbside recycling until the reporting of this story.

“You know, there’s an old saying, ‘Reduce. Reuse. Recycle.’ We’re focusing right now on the last part of that,” he says. “‘Reduce’ is what we’re supposed to do first, and then reuse things, and then, if we can’t get anything else out of it, we recycle … We got to back up and go start using less stuff.”

To listen to the full conversation between listener Kim Hunter and Zero Waste Detroit’s Galen Hardy, click the player below.

WDET’s Gabrielle Settles contributed to this article.