Possible Resting Place of Great Lakes’ Most Iconic Shipwreck Unveiled With Photos and New Book

Steve Libert and his wife Kathie have been gathering historical information about the Griffin for over 40 years. Now, they think they’ve found it’s final resting place.

The group searching for the remains of a 17th-century French ship says it has found what appears to be a colonial-era wreck in northern Lake Michigan. Photographs on Great Lakes Exploration Group’s website show the frame of a boat somewhere in the waters off the Garden Peninsula in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. The group’s leader, Steve Libert, and his wife Kathie, released a book this week detailing historical information they have gathered over 40 years, explaining why they believe the wreck is the Griffin.

Libert’s search has been a contentious one, involving a federal court battle with the State of Michigan that lasted more than a decade. A visit from France’s top marine archeologist in 2013 ended in a split among the researchers working on the site. The French team agreed with Libert that a beam of wood taken from the lake that June was likely the bowsprit of a ship. American scientists concluded it was probably a piece of a commercial fishing net. The beam was not attached to anything and no ship was found.

Steve Libert resumed his search with members of his original team, friends he had met in Dayton, Ohio while learning to scuba dive in the early 1980s. In 2018, they dove on a location that Libert first located using Google satellite imagery, a site he says his crew had probably motored over in a boat “100 times.”

Libert says numerous details about the site suggest a very old ship. He says the metal fasteners are not threaded. The wooden pegs are constructed in the manner of 17th-century shipbuilding and the nails are handmade of wrought iron. “There is nothing on that vessel that I can find that says, ‘that’s a modern-day vessel,” Libert said.

Le Griffon and the Huron Islands 1679 Details the Decades Long Search

The book released this week lays out in detail the research the Liberts have spent most of their adult lives engaged in, searching for the elusive vessel sailed by French explorer Rene-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle. The Griffin disappeared returning from its maiden voyage in 1679 and was last seen struggling in a storm near what is now Washington Island in Wisconsin.

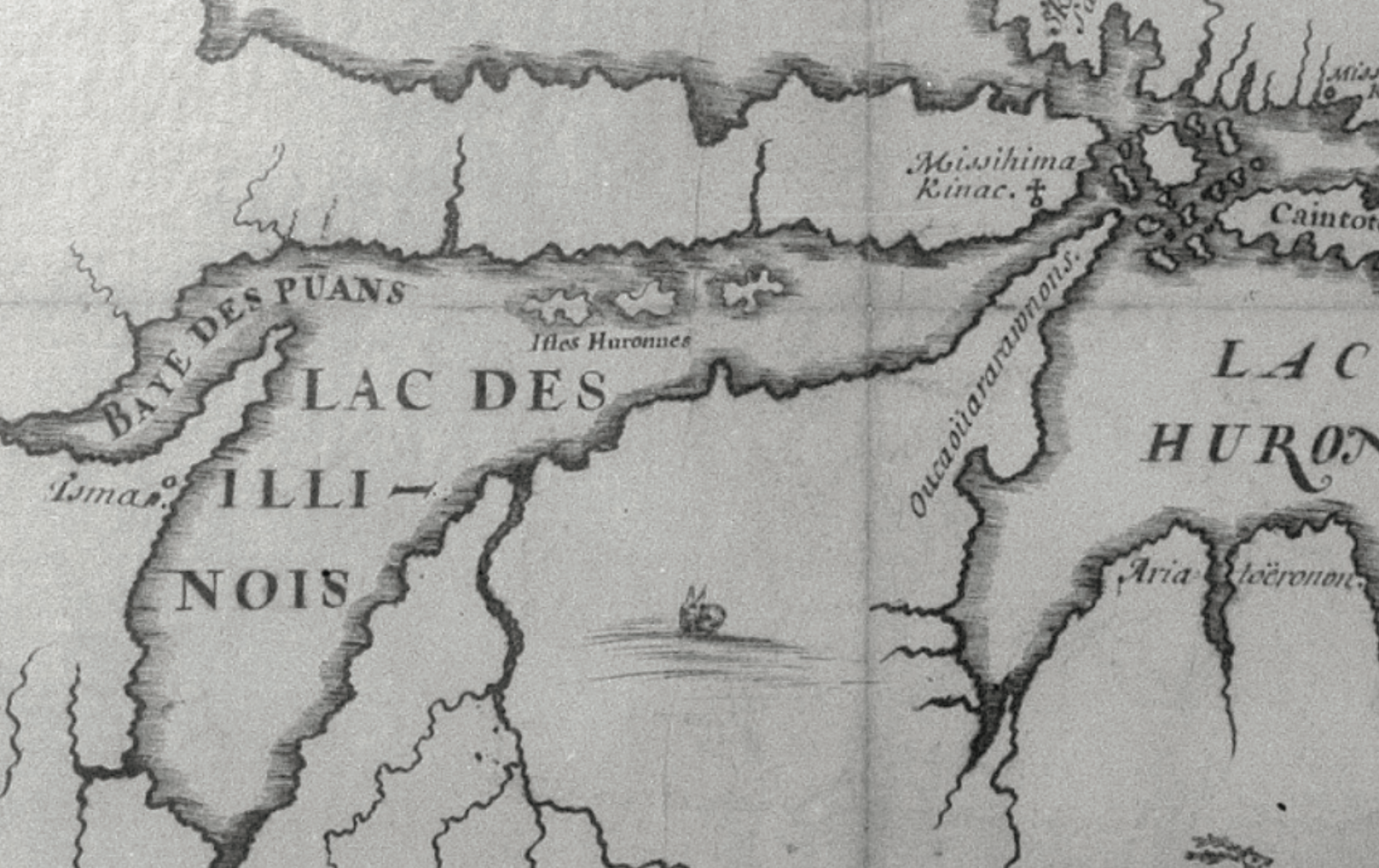

The book’s title, Le Griffon and the Huron Islands 1679, indicates the importance the couple places on understanding the location of the Huron Islands in their search. They say people have believed the islands were in Lake Huron or were possibly the Beaver Island archipelago. The Liberts assume they are the islands that stretch between the Door Peninsula in Wisconsin and the Garden Peninsula in Michigan’s U.P.

The book constructs the story of the Griffin using various clues they have uncovered: old maps, scientific analysis of objects like the beam recovered in 2013, and the writings of La Salle and others, like the missionary priest Father Louis Hennepin who sailed on the Griffin.

“We had to almost produce a detective book,” says Kathie Libert, “a mystery book based on the facts.”

They say those facts point to a “high probability” that what they have found is La Salle’s lost ship. They call for a thorough investigation of the site by academic researchers and French archeologists.

A Collaborative Effort Finding the Griffin

The Liberts have been working with a shipwright and diver named Allen Pertner. Originally from Northport, Pertner has been studying boats since the 1950s, when he found the wreck of a steamboat that had exploded and sank on Lake Leelanau.

Pertner says he has never seen a ship frame like this and every piece of this boat was handcrafted. He says the lake bottom is also littered with wooden pegs that are tapered from the center.

Pegs like this, called treenails or trenails, were used in ship construction. Pertner suggests the explanation is this boat was carrying a shipload of wooden nails, likely to be used building La Salle’s next ship as he sought to extend French dominion down the Mississippi River into the heart of North America. “Why else would you have that stuff there?” asks Pertner.

Any further exploration will require permits from the state to disturb or excavate the site. That’s because Michigan controls the bottomlands of all its Great Lakes waters. The state turned down a proposal from Great Lakes Exploration Group to further assess this wreck.

Ken Vrana is an archeologist who recently retired from Michigan Technological University and has worked with Steve Libert in the past. He says there is no way to tell from the photos on the website whether the ship is the Griffin or not. He says the state should give his team full access to the site.

“It confuses me why they denied the permit in the first place,” says Vrana, “except it was Steve Libert.”

Libert has been at odds with the state officials and other marine archeologists for decades. Professionals tend to take a low view of avocational explorers, sometimes deriding them as treasure hunters. Libert has accused them of trying to steal his discoveries out from under him, using governmental authority to find objects he has searched diligently to locate.

As a result, the Liberts have no expectation that the state will allow them to do further work at this new site. That’s why they wrote a book, to lay out all their research for anyone to see and decide whether they have found the holy grail of Great Lakes shipwrecks.

“I don’t know what else you can come up with honestly, by the time you see the facts,” says Kathie Libert.

Trusted, accurate, up-to-date

WDET is here to keep you informed on essential information, news and resources related to COVID-19.

This is a stressful, insecure time for many. So it’s more important than ever for you, our listeners and readers, who are able to donate to keep supporting WDET’s mission. Please make a gift today.