Tale of the Michigan Polar Bears

World War I had ended, but the Polar Bears were still at large on the Russian frontier.

Standing at a cemetery in Troy, Michigan is a polar bear carved from a solid chunk of white marble. It’s the focal point of a monument that, including its base, is about eight feet tall.

Larry Chase walks around the statue. He draws attention to the series of flat headstones on the ground.

“And over here is the platoon commander,” says Chase. He sweeps his foot over the heavily oxidized name plate, brushing away leaves.

“His name is Harry Mead. He wanted to be with his people and he’s about as close as you can get. And over here is Victor Stier…”

Chase continues about the grounds, recalling the men beneath the headstones. They were soldiers around the time of World War I, and the polar bear statue is their memorial.

“It was dedicated on Memorial Day — May 30th, 1930,” says Mike Grobbel, President of ‘Detroit’s Own’ Polar Bear Memorial Association. “It was a ceremony attended by allegedly 10-thousand people.”

Larry Chase is also a member of the association. His official title is Guardian of the Bear.

“I’ve gotten that title because I live so close and I’m out here quite a bit,” Chase explains. “If there’s anything going on out here I’ll find out about it.”

And it doesn’t take him long to notice that something is… different.

“The Army flag is missing, and it looks like they put it upside down. Ya know what I mean? The rope… because where they put it. Unless the one clip is broken, I bet ya that’s what it is.”

While Chase investigates, Grobbel points out the large, green marker next to the flag pole.

“This site has a state of Michigan historical marker,” says Grobbel, “that was dedicated in 1988.”

The sign gives a brief explanation of who the Polar Bears were — a group of soldiers who were mostly from Michigan, and largely from the Detroit area. In fact, newspapers of the day referred to them as ‘Detroit’s Own.’

But beyond local ties, the Polar Bears also played a unique role in American history.

Summer 1918. World War I is in full swing across Europe. Behind the scenes, the Bolshevik party has come out on top of a civil war in Russia. They’ve signed a peace treaty with Germany, effectively ending the war on the eastern front.

Grobbel says the move spelled trouble for the Allied forces.

“The British and French knew that the Germans would now start moving large numbers of divisions from the Eastern Front to the Western Front,” he explains. “So they wanted to intervene.”

Enter a group of fresh trainees from Camp Custer in Michigan. They arrived in Liverpool, England ready to fight on the Western Rront, but there was been a change of plans. About 5,000 troops, mostly from the 339th Infantry Regiment, were retrained and sent to engage in the Russian Civil War.

“By doing so,” says Grobbel, “they could put pressure on Germany to keep divisions on the Eastern Front.”

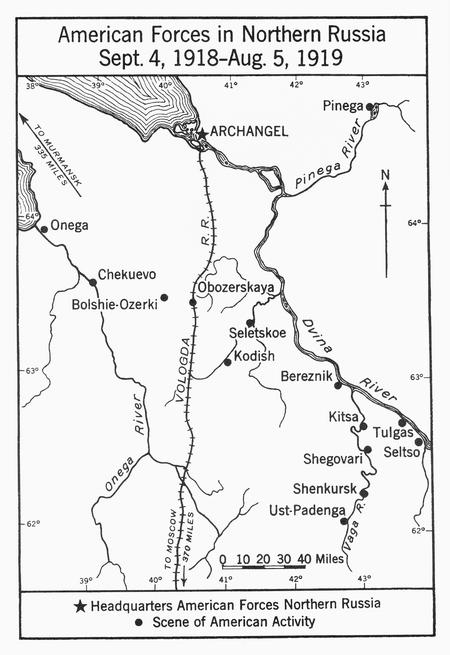

They arrivee in Russia and were split into two groups. Those on the “North Russian Expeditionary Force” were stationed in the town of Archangel, and became known as the Polar Bears.

November 1918. The Armistice deal is officially signed, ending World War I. But while other U.S. troops came home, the Polar Bears were still fighting.

Grobbel says his grandfather, Clement Grobbel, was one of the Polar Bears.

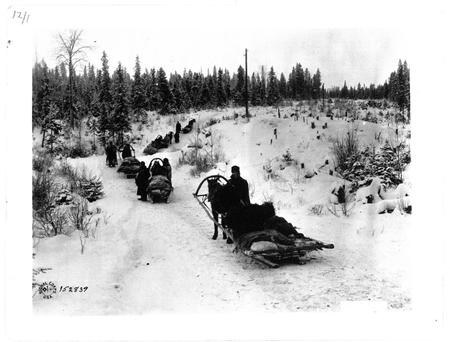

“We have some of my grandfather’s letters,” he explains, “and his letters were pretty heavily censored so he couldn’t talk too much about what was going on. He mentioned that ‘we advanced down the railroad lines one little village at a time’ and ‘it’s great fun.’ That was the way he put it to his mother.”

Grobbel says the families at home could read between the lines. New Years Day came and went — still no word of the Polar Bear’s return. They knew something wasn’t right.

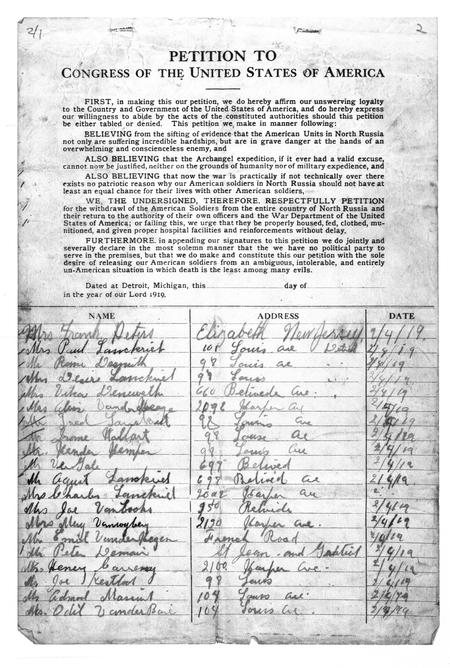

February 1919. Early in the month, simultaneous rallies were held in Grand Rapids and Detroit. The families petitioned the U.S. government for the return of the Polar Bears soldiers.

“That did have an effect,” says Grobbel. “It also generated a lot of interest in the (U.S.) Senate.”

Politicians in Washington D.C. began lobbying for the soldiers’ return. After about two weeks, the announcement was made. The Polar Bears would return home at the nearest convenience.

“They had to be vague on it,” explains Grobbel, “because the reality was they couldn’t get out until the rivers thawed. And at that northern latitude, 130 miles south of the Arctic circle, the rivers don’t break up until mid-May.”

That meant the Polar Bears would have to continue the war. Ultimately, the soldiers would spend another four months in combat before returning from Russia.

July 1919. After spending about one year abroad, the Polar Bears began to return home, where they were greeted with a heroes’ welcome. On Independence Day of 1919, a parade and picnic was held in their honor on Belle Isle.

But once the celebrations ended, Grobbel says the story of those Michiganders who fought in North Russia faded from public memory.

“When the men came home, this quickly got swept under the rug,” says Grobbel. “Because it was a military intervention and we left before things were decided one way of the other. And even if we had stayed, it would’ve been a loss.”

That brings us back to the polar bear statue and its guardian, Larry Chase.

“We call the statue Boris,” says Chase. “From Boris and Natasha (from the Rocky & Bullwinkle cartoons).”

Every year on Boris’ birthday (Memorial Day), the Polar Bear Memorial Association holds a ceremony to remember the veterans of the North Russia campaign.

“Before Memorial Day, we clean him up and brush his teeth and get him all ready to go,” he continues. “I see the geese have been on his head. They’ve left some surprises for next year…”

When Boris was dedicated in 1930, several Polar Bear soldiers were reinterred on the grounds. It had taken until the summer prior to retrieve their bodies — a full decade after the conflict had ended.

Mike Grobbel says those efforts required a covert operation.

“We did not have diplomatic relations with Russia,” he explains, “so they had to do it undercover. The men went up dressed as peasants — some of them were former 339th. And they were able to get 86 bodies back.”

To some, the Michigan soldiers who fought in North Russia may represent a forgotten chapter at the end of World War I. But it’s also significant for another reason, as it opens a saga that would come to define the next century of American history.

That’s because story of the Polar Bears is also the story of the first conflict between the United States and the Soviet Union.