Shustho: How language access affects health care for Bangladeshi women in Michigan

Nargis Rahman March 19, 2025Community organizations like the Detroit Friendship House in Hamtramck are working to bridge the language gap.

Editor’s Note: This story is part one of a new four-part series from WDET’s Nargis Rahman called, “Shustho: Mind, Body, and Spirit,” exploring health care and health care access for Bangladeshi women.

Michigan is home to the third largest population of Bangladeshis in the U.S., with a significant number living in the metro Detroit area.

Bangladeshi immigrants struggle with a number of challenges when trying to access health care, including language, cultural competency and adequate insurance.

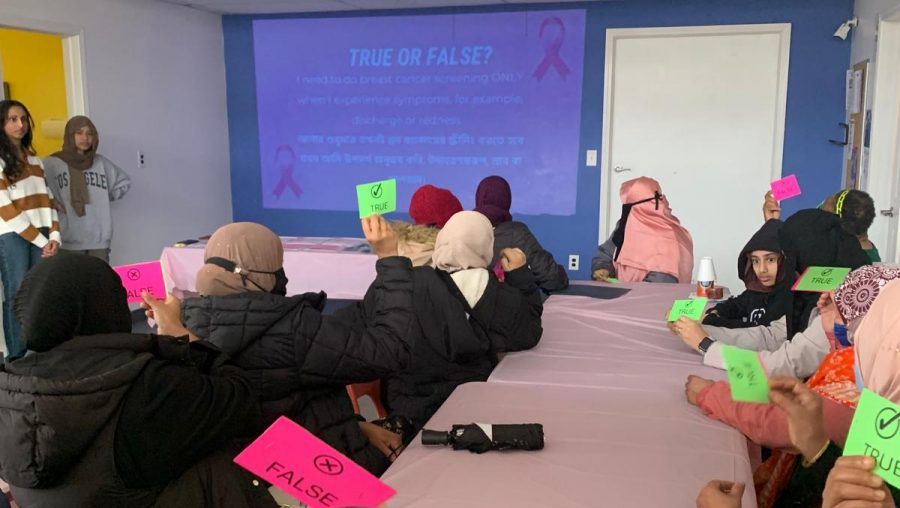

Community organizations like the Detroit Friendship House in Hamtramck are working to bridge the language gap many Bangladeshi women in southeast Michigan face when trying to access health care.

The nonprofit provides health education workshops to help them understand and navigate the health care system.

Khurshida Hossain is the executive director. She says women are the lifeline to their families.

“It’s the mothers that come to pick up food, and we need to understand that women, even though if they don’t have access to education or transportation, they’re the ones putting the meals together, they are the ones that have more autonomy over the nutrition and the well-being of their children, and that’s important to us,” she shared.

The organization holds workshops on topics like women’s health, nutrition, and chronic illnesses. But information alone isn’t enough to educate women about their health. Hossain says making health care more approachable is essential.

Workshops are paired with direct enrollment into health care services to help women navigate complex systems.

“Having them enroll on the spot and explaining those medical terminologies, or having someone that can translate that on the spot makes it more accessible, rather than having just a workshop and saying, ‘Okay, now you have to go here, downtown somewhere, to enroll and speak to a certain person that’s very disconnected and very intimidating,’” she said.

In 2018, Detroit Friendship House partnered with Eastern Michigan University’s Racial Ethnic Approaches to Community Health program (REACH) to create more targeted workshops.

Hossain says a key goal was to help Bangladeshi women learn English so they could better advocate for themselves at the doctor’s office, instead of relying on a translator or their child to provide interpretation services.

“Instead of taking the registration form and handing it to a translator or their child to fill out this sensitive information, they are empowered to answer those questions and fill out those forms themselves,” she said.

The organization also encourages women to sign up for free mammograms and pap smears to educate them about breast and cervical cancer.

Volunteers like Mst Begum, a student at Hamtramck High School, play an essential role. She serves as a translator.

“I was chosen because I’m also Bengali, and I had an easier time connecting with the patients,” she said.

She says part of her job is breaking down stigma.

“That is so necessary to have people who are Bangladeshi trying to get people who are Bangladeshi to sign up for these programs because they feel more comfortable and confident,” she explained.

The growing need for health care workshops for Bangladeshi women

A decade ago, providing culturally specific health education for Bangladeshi women was rare. Dr. Subha Hanif, a cancer rehabilitation fellow at the University of Michigan, started a similar effort in the metro Detroit area in 2012 through her organization Bangladeshi Americans for Social Empowerment.

“I felt this like, this disconnect between the resources being there and then the community, nothing really bridging them together,” she said.

She worked with Beaumont Family Medicine to create women-only health workshops. But gaining support for the program wasn’t easy.

Traditionally, men in the Bangladeshi community would gather information and relay it to their families. Hanif had to convince the elders that women needed their own space to acquire health education.

“I had to do a lot of sitting down with, you know, the uncles in our community and making them understand that if you send your wife here, she’s going to be more empowered to learn about her health,” she added. “She’s going to inadvertently help your family, your children and your health, and she’s going to be more empowered to take care of herself better as well.”

Hanif says many women said they benefitted from these spaces and learned how to ask more questions about their health care.

But language barriers go beyond just medical terminology.

Sylheti-speaking interpreters, health care workers, are in demand

Zak Ahmed is an interpreter for the U.S. Department of Justice and several Michigan hospitals. He says many Bangladeshis in the state speak Sylheti, a dialect used by 11 million people in the world. However, interpreters often speak Shuddo Basha at institutions, the standardized formal Bengali language.

“When I used to do the asylum cases and immigration court, we’ve seen so many people that they are denied or deported because of the language barrier. So we found out that they don’t understand these are, these are basically Sylheti speakers,” he said.

Ahmed says the U.S. Department of Justice added Sylheti as a separate unique language in 2018.

But he says there is still a need for more Sylheti-speaking interpreters, although many patients don’t realize they can request one.

“They do feel much better actually, when they speak their own dialect. They can feel better when they see someone that they can understand their needs,” he said.

The Michigan Department of Health and Human Services says interpreters are available at no cost for anyone who needs one, including in Bengali.

Last year the state also passed the Meaningful Language Access to State Services law to prompt government agencies to translate important documents in different languages.

However, more bilingual speakers in health care are needed.

There isn’t a formal health care language certification for Bangla or Bengali in metro Detroit, like the one offered in Arabic for health care workers at Wayne State University.

Khurshida Hossain from the Detroit Friendship House says it’s important to amplify efforts to increase the number of Bangladeshi Americans entering health care.

“Then you have doctors and nurses and pas that not only can speak and understand the language, but that look like the community, and it makes that doctor’s appointment that much less intimidating, that much more accessible,” she said.

Language access is a delicate balance between learning health care terminology, advocating for themselves, and finding resources like interpreters for Bangladeshi women in southeast Michigan.

Trusted, accurate, up-to-date.

WDET strives to make our journalism accessible to everyone. As a public media institution, we maintain our journalistic integrity through independent support from readers like you. If you value WDET as your source of news, music and conversation, please make a gift today.

Author

-

Nargis Hakim Rahman is the Civic Reporter at 101.9 WDET. Rahman graduated from Wayne State University, where she was a part of the Journalism Institute of Media Diversity.

Nargis Hakim Rahman is the Civic Reporter at 101.9 WDET. Rahman graduated from Wayne State University, where she was a part of the Journalism Institute of Media Diversity.