Incarcerated artists find creative outlet through annual U-M exhibition

Karen Brundidge December 27, 2024The university’s Annual Exhibition of Artists in Michigan Prisons is one of the largest exhibitions of incarcerated artists’ work in the world.

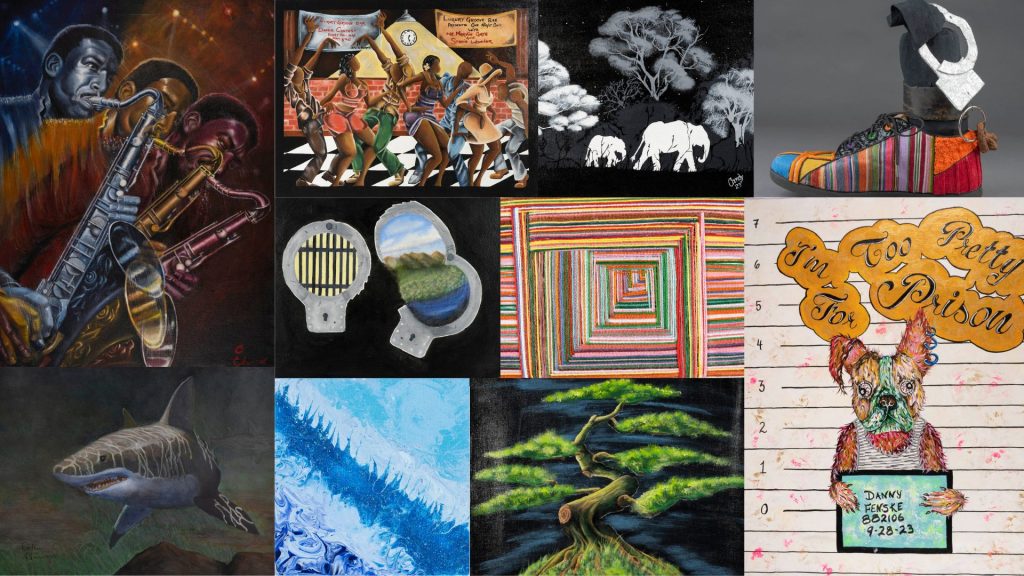

“Coltrane in Motion” by Curtis Chase (Top row from left); “Luxury Groove Bar” by ꓘeith Burns; “Starry Safari Waves” by Candy Lawson; “Enough is Enough” by Susan Brown; “Untitled” Dewitt Gallahan AKA Stained (center left); “Faraway” by Heavan (center right); “Please don't go in the water, Please” by Arthur E. Harriger (bottom row from left); “Tidal Waves” by Dayleisha Henderson; “Bonsai Tree” by David Lester; and “Beauty is in the Eye of the Beholder” by Danny Fenske.

The holiday season is extra special to Nora Krinitsky.

“Every year we travel to every prison in the state, we meet with artists, we talk to them about their work, we give them feedback and we select art that we want to bring back to Ann Arbor and exhibit in the show.”

Krinitsky is the director of the Prison Creative Arts Project (PCAP), a program at the University of Michigan that offers prisoners the opportunity to create and exhibit art.

Its “Annual Exhibition of Artists in Michigan Prisons” is one of the largest exhibitions of incarcerated artists’ work in the world. The exhibition features art from all Michigan prisons, and allows the artists to keep 100% of the proceeds from sales.

“It’s really eye-opening for folks to come into the gallery and see the art that people are creating under really restricted circumstances,” she said.

There are certain themes and ideas that are prevalent in artists’ work. In many of the pieces, the “natural” world is a theme depicting animals and landscapes. Krinitsky believes it’s a way for the artists to imagine themselves in a different setting than where they are at the moment. There are other themes on their minds as well.

“We do see a lot of pieces where people are thinking about time,” she said. “Thinking about the passage of time, what time means to them; and that really makes sense to me since time is very much how incarceration is measured.”

Krinitsky says they display art from a wide range of technical abilities, from masterful painters to those just beginning to make art. She says creating gives them a meaningful outlet.

“It’s a really important way to offer some agency, to have some control and some ability to express yourself in an environment where you otherwise have absolutely no control,” she said. “There’s something particularly compelling about having no freedom that really moves people to start creating, to express themselves and quite literally be seen, when otherwise they are literally not seen.”

Martín Vargas was incarcerated for 46 years. He entered into the penal system at 17 years old. While in prison he says he examined his surroundings and wondered if that would be all there ever was for him. Vargas wanted more for himself, and wondered who he was. He says he realized he was stuck and had to get out of there, it’s tough for many who were separated from the free world.

“Coming out of prison is not a very good experience at all. Some of us feel lost, some of us feel confused, it’s like we don’t belong out here in the community sometimes,” he said.

The Linkage Project serves a group of artists who were formerly incarcerated, and is a part of PCAP. Members are provided with professional development, artistic workshops and a peer support network. They also have the chance to perform or exhibit their creations.

Vargas is a painter who describes his work as eclectic. He has participated in the annual art exhibition and is now a curator with the Linkage community.

While in prison, Vargas obtained his high school diploma, as well as his associate’s and bachelor degrees. As a self-taught artist, he researched and practiced often to hone his craft. Now he enjoys motivating and inspiring people with his story.

“Eventually I realized that in fact, I’m an artist. The people that supported me by buying some of my work — just about all of the work that I created — gave me the confidence that I needed to realize that this is what I am supposed to do in my lifetime,” he said.

Vargas says creating art is therapeutic for him. He started going beyond the “hustle” — from making money and designing tattoos for the guys inside, to creating fine art. Eventually, he taught in the prison facility for more than 20 years as an art tutor. He says creating art became more than an escape, it gave him a sense of peace and purpose.

“Psychologically it healed me. It gave me a better sense of myself. It gave me a great sense of peace and calm and it made me realize that every time I was working on a painting or reading about art or creating sketches, every minute that I was doing that, my mind and actually my life, was not really in prison.”

Getting commissions for his work helped Vargas gain confidence. Still, obtaining art supplies was a challenge that he and others had to overcome.

“An artist is going to create art with whatever materials she or he has at the time. And because materials are not so easily obtained inside prison, we had to create art with whatever’s available.”

– Martín Vargas, local artist who served 46 years in prison

They were not able to buy paper or paint at will. That pushed them to become resourceful. Those locked behind prison gates use pieces of sticks or toothpicks if they can get access to those materials. Vargas says they use sand, dirt, and grass if possible, or even four-inch pencils to create their art.

“An artist is going to create art with whatever materials she or he has at the time. And because materials are not so easily obtained inside prison, we had to create art with whatever’s available,” he said. “Little pieces of branches, wildflowers that exist in the yard, or string, yarn, candy bar wrappers, cardboard…”

Vargas says the artists get good responses from the public at the exhibitions, noting how freeing it is to have people associate you with your work, as opposed to your status as an inmate. He says the positive energy fuels him to keep creating, with some patrons even writing letters to the creators to give feedback.

“When somebody gives me that label as a real artist, it justifies, and gives me such a feeling of accomplishment, because it’s not like you’re a good prison artist, no, you’re a good artist, period,” he said.

The annual exhibition runs spring 2025 from March 18 through April 1 at the Duderstadt Gallery on U-M’s campus. The Prison Creative Arts Project also holds exhibitions of incarcerated artists’ work throughout the year.