CuriosiD: What’s the story behind Black motorcycle clubs in Detroit?

In this episode, we dig into the history and culture behind Black biker clubs in the city.

Detroit Gentlemen Motorcycle Club, located on Detroit's west side, is among several active Black motorcycle groups in metro Detroit.

WDET’s CuriosiD series answers your questions about everything Detroit. Subscribe to CuriosiD on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, NPR.org or wherever you get your podcasts.

In this episode of CuriosiD, we answer the question:

What’s the history of Black motorcycle clubs in Detroit and what’s it like to be in one?

The Short Answer

The first all-Black motorcycle club with nationwide chapters was born in Detroit, two years after the 1967 riots erupted in the city. Members of the Outcast Motorcycle Club say the group formed because of segregationist policies practiced by some racist, white bikers. Like most motorcycle clubs, Black groups follow what they call the “biker lifestyle” which includes the freedom to cruise when and where they want, an invitation-only process to become a member and an intense trust in those who eventually join them on the road.

The fraternity of the highway

Travel around Detroit and there are countless private clubs protected by things like iron bars along many roadways.

A close look reveals logos on some of the buildings with names identifying them as the property of the Hell Raisers, Soul Stars or the Black Syndicate, among many others.

It’s the signs of a motorcycle club.

Bikers play a distinct role in both the history of the “car” capitol of the country and in the Black community that makes up the majority of the population in the city that put the world on wheels.

The road to understanding that equation leads to buildings like a dark, squat Detroit clubhouse near Highland Park.

Streetlights bounce off of chrome here, while a deep-throated rumble echoes from the handful of Harley Davidson motorcycles parked in front.

This is the home of the Black Syndicate Motorcycle Club.

It’s one of as many as three dozen biker clubs in-and-around Detroit, though experts vary widely on the precise number.

Several men in leather are lounging near one with a white beard and a commanding presence, wearing a worn vest emblazoned with the words “National President.”

“They call me Take Cover.”

It’s the kind of rider name he says bikers give each other, in part to limit any chances of retaliation from rivals.

But Take Cover says he helped found the Black Syndicate about a half-century ago to create a refuge from the violence he’d already seen.

“I served in Vietnam,” Take Cover says. “I got wounded over there. Came home. Some of the other guys that was in the Korean war, they was bikers and we decided we’d just form a brotherhood club. Something where we could ride and enjoy each other, a family-type thing.”

A shelter from the storm

Take Cover says those who fought for freedom find it on the grips of their handlebars.

“That’s where we started out at, to release our stress,” he says. “I have a problem with the wife, get on my motorcycle, take a nice ride and chill out and come back, my problem’s solved.”

He nods towards the club building, where bright lights, loud talk and pulsating music escape into the night each time a door opens. Take Cover says it works as a kind of safety valve.

“I tell these guys, ‘Hey! When you go to work and you have a problem on your job and you might done spent your last dime, you just come down to the clubhouse and chill out. And just talk to your brothers, your brothers and your sisters.’”

Take Cover says, like many motorcycle clubs, the Black Syndicate’s “family” extends to the nearby neighborhood, with members helping to cut grass in overgrown areas or donating to charities like veterans’ groups.

But he says there are also rivalries among some clubs. Rivalries that can turn deadly.

“There was a shootout,” Take Cover says, noting it did not involve any members of the Black Syndicate. “We called all the presidents of the clubs here in Detroit together to make sure that this don’t continue and that there’s no retaliation. Because we don’t want this in our city. It’s OUR city.”

Outriding segregation

About two years after riots enveloped Detroit in 1967 — a rebellion many say was driven by African Americans who were fed up with attacks from white, racist police officers — a group of bikers created the first all-Black club that eventually spread nationwide: the Outcast Motorcycle Club.

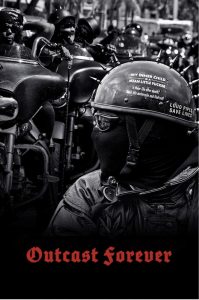

It spawned a documentary film called “Outcast Forever,” which told the story of Black riders banding together in the face of opposition from some white biker clubs.

In the film, one Outcast member recalled a Detroit landscape at the time he says was far from welcoming for many African Americans.

“Segregation was very strong then. And it made us feel this [club] was our family. This was our thing away from the segregation, away from the racism, ’cause we were doing our own thing.”

The film paints an impressive picture of all-Black riders in all-black clothing rolling through towns that members claim had never seen such a thing before.

Even decades later, Detroiters like Andre Seewood say Black motorcycle clubs retained a reputation for being tough…and partying hard.

Seewood says he decided to find out for himself when he joined some friends for a night out at a biker clubhouse.

“It was hidden behind these bushes and trees. And there was a guy standing in front of a wrought iron gate with an AK-47 rifle. And I was like ‘What am I going to?’’

But Seewood says he was reassured by someone who regularly attended biker club parties – his sister.

“It’s a safe space, that’s the way I got it,” Seewood says. “I knew my sister was going. I was worried. And she made it clear that nothing’s going to happen there in terms of violence or anything like that. Because of the armed guards that were there and the sense of, ‘We’re here to have fun, not to get involved in any violence.’”

A bike and a lifestyle

There are, however, clubs where danger is a real factor.

Bikers in “one-percenter” motorcycle clubs are known as the “baddest” riders on the highways, no matter what their racial make-up is.

Some one-percenter clubs, in Detroit and across the country, have members who’ve been convicted of everything from murder to drug trafficking. They appear to be the exception, overall, in terms of crime.

More common among the roughly 99% of other clubs are the massive group rides many take to raise money for charities. Many include former members of the military or ex-police officers and firefighters. Others, like Detroit’s Untouchable Riders, even welcome those who have barely been on a bike.

“On a hot summer day in Detroit there’s a thousand of you out there.”

-Clutch, member of Detroit’s Untouchable Riders

Take the case of a club member who now goes by the rider name “Clutch.”

“When I bought my first Harley I didn’t know how to even ride it. And I kept thinking I knew what I was doing until I burnt the clutch out on the bike. And they gave me the nickname of Clutch.”

He says Untouchable Riders draws from many walks of life, including government employees and business owners.

But Clutch says they still share something with every other motorcycle club: the passion for the open road and the freedom it represents. That, and an unshakable trust in a club’s fellow riders.

“On a hot summer day in Detroit there’s a thousand of you out there. And you feel OK. I done broke down on the side of the road and a guy pulled up on me on the same bike I had. He says, ‘I see a brother. He needs help.’ And it make you feel good.”

Clutch calls it the bedrock of the “biker lifestyle.”

And even after a half-century since segregation drove Detroit’s Black bikers to create their own club, that lifestyle keeps rolling on.

Meet the listener

Nick Harrell works at an indoor rock-climbing gym in Detroit’s Eastern Market. The 30-year-old Highland Park resident says the job has its risks, but “adventure is not without risk.” Curiosity drove him to check-out one of the many biker clubhouses he often passes on his ride home, even though Harrell says he is “terrified” of motorcycles. But now, having been to a motorcycle club, Harrell says he’s considering at least buying a moped, as a kind of “gateway drug” to moving on to the big bikes.

We want to hear from you!

If there’s a question revving-up your brain cells , let us know here or fill out the form below.

More from CuriosiD: