A new Detroit ordinance will pay for lawyers for low-income people facing housing issues in court

The “Right to Counsel” ordinance was passed unanimously last week by Detroit City Council.

Toshiba Ford lives with her significant other in her mom’s townhouse on Detroit’s west side. Ford says the place has rusty nails on the bathroom floor, a leak in the kitchen and mold.

“All my disabled mother wanted was simple repairs done,” Ford says. “And now they want to throw her out.”

On New Year’s Eve, Ford says her mother received a letter stating that she was being evicted. The property manager said it was because Ford’s partner allegedly threatened a plumber.

“There was never a threat to the plumber. There was speak of frustration because they steadily sent the same plumber out that never corrected the repair. And we were frustrated,” says Ford.

Regardless, Ford and her family were faced with an eviction.

“It’s been mentally stressful. It’s been physically stressful,” she says with exasperation.

After feeling confused and overwhelmed, the family finally received help. Ford was connected to a lawyer from the nonprofit United Community Housing Coalition. He was able to negotiate an extra three months for Ford’s family to move without getting an eviction on their record.

“We need resources to lawyers, to legal people to help us in situations like this,” says Ford. “You cannot do this on your own. You need help.”

Ordinance in the works for more than 2 years

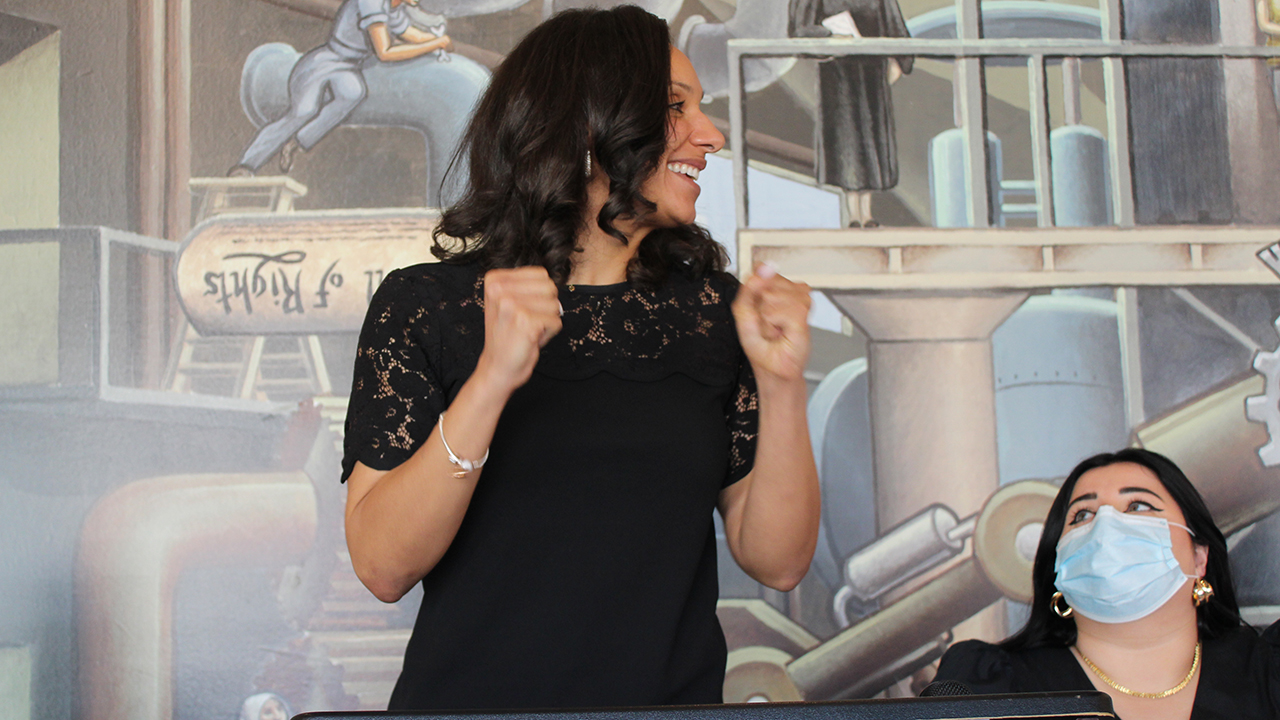

A new Detroit ordinance that was passed unanimously by City Council on May 10 will do just that. It’s called the “Right to Counsel” ordinance. It provides attorneys to low-income residents facing eviction, foreclosure and issues related to land contracts. The legislation has been in the works for more than two years. It was drafted by Detroit City Council President Mary Sheffield in collaboration with the Right to Council Coalition, a group of lawyers and grassroots organizations.

“Out of the 30,000 eviction cases in Detroit, only 4% of those tenants had an attorney,” says Sheffield. “Also, half of all of the evictions that took place in Detroit could have been avoided if they had an attorney.”

Sheffield says evictions disproportionately impact households headed by Black women, seniors and people with disabilities. But she says the ordinance isn’t only about the people who are facing displacement.

“I think it’s about, in my opinion, more importantly, stabilizing our neighborhoods. Because when people are evicted it causes blight, which continues to deteriorate our communities and our neighborhoods,” says Sheffield.

In Detroit an individual is 18 times more likely to remain in their home when they have a lawyer to help them during an eviction, says Tonya Myers Phillips, a leader of the Right to Counsel Coalition and one of the attorneys who helped draft the new rule. Myers Phillips says the ordinance is not only expected to keep Detroiters in place — it’s expected to preserve money in the city.

“Detroit receives an estimated $3,751 annually per resident in non-reimbursable federal funding,” says Myers Phillips. “So, when an individual is evicted and moves out of the city of Detroit, which is a trend that we noticed that’s happening as well, that federal funding is lost.”

Where will the money come from?

While preventing evictions could help the city retain some funding, paying for lawyers will of course cost the city money. The Right to Counsel Coalition estimates that it will take about $17 million a year to fully cover the need. Detroit has budgeted $6 million in American Rescue Plan Act funds to pay for the program in its first year and City Council hopes to do the same for the second and third years. But it’s unclear where funding will come from when ARPA money runs out. The ordinance says any county, state and federal funds or philanthropic dollars can be used. But the city’s top lawyer, Conrad Mallett, says Detroit’s constitution makes it clear that money cannot come from the city’s general fund, which receives revenue from income taxes, property taxes and more.

Council President Sheffield says this is a setback but she and the coalition are optimistic future funding for the ordinance can be secured from the general fund or elsewhere.

“We want to get through the first two years and then when we have about a year out, we’re gonna go back, hopefully revisit this conversation of general funds, and then also look to see if there’s additional state, county or federal funds that can possibly be utilized to keep the program going,” says Sheffield.

At least 15 other cities and three states have found a way to fund their own right to counsel programs. New York City’s law, which passed in 2017, is funded with general revenue. A report from NYC’s office of civil justice found that, of tenants who acquired attorneys, roughly 85% were able to stay in their homes.

The lawyer labor pool

But New York’s model isn’t without issues. An article by Curbed reported that some organizations tasked with providing legal services to tenants in the city announced in April they would stop taking clients for at least a month because they did not have enough lawyers on staff to keep up with the court’s schedule of landlord and tenant disputes.

William McConico is the Chief Judge of the 36th District Court in Detroit. He says with about 320 cases a day, a lawyer shortage is a possibility here as well. But he points out that his housing court is unique from New York’s in that in Detroit it’s still all virtual.

“It’s a lot easier for one lawyer to handle multiple cases in a Zoom room,” says McConico. “If we were in person, you would have to probably have almost 10 times the amount of lawyers.”

Listen: “You cannot do this alone”: How the new ordinance aims to help Detroiters facing eviction.

McConico says you can fit more people in a Zoom room than you can in a physical courtroom. He says 1-2 lawyers can handle an entire docket virtually so you wouldn’t need to staff as many lawyers. On top of that he says a lawyer shortage could be avoided with the right recruitment.

“After the pandemic, I believe people are more socially conscious. They are looking towards things such as shelter, things such as water rights,” says McConico. “And you have younger lawyers that aren’t just looking to make money as lawyers but they’re looking to do something for the community.”

McConico says he supports the new ordinance because it will make eviction proceedings more efficient since judges won’t have to explain the legal process to non-represented defendants. And more importantly, he says, it will make the process fairer.

All photos by Laura Herberg except for eviction stock image

Trusted, accurate, up-to-date.

WDET strives to make our journalism accessible to everyone. As a public media institution, we maintain our journalistic integrity through independent support from readers like you. If you value WDET as your source of news, music and conversation, please make a gift today.