Tracked and Traced: Does Project Green Light in Detroit reduce crime?

Laura Herberg February 3, 2022In this episode of “Tracked and Traced,” Laura Herberg investigates the pros and cons of Detroit’s controversial surveillance program, Project Green Light. Then, Eric Williams of the Detroit Justice Center talks about how increased police surveillance affects Detroiters.

A sign for Detroit's Project Green Light program hangs outside of a gas station.

Listen and subscribe to Tracked and Traced:

Apple Podcast — Spotify — NPR — Stitcher — Google Podcasts

In order to participate in Project Green Light, businesses must pay for the installation of required cameras, signs and additional lighting, a cost of around $5,000. On top of that initial investment, businesses have to pay for high-powered Wi-Fi to transmit video. Manager Ismail Salah says the expense has been worth it for his station. He says he’s gotten good feedback from his customers since joining the program about five years ago.

“Before at night they’d be afraid but now they’re happy,” Salah says.

Indeed, almost every customer I talk to here is a fan of the program. David Hunter says he likes that the place is monitored 24/7. “I feel really comfortable when I come to this gas station. It’s my favorite one,” says Hunter.

Customer Keshia Johnson says she feels more at ease patronizing Green Light stations. “So, I always come here because I make sure I’m safe,” she says.

Salah says thefts and other crimes still happen but he feels like incidents have decreased since the business joined Green Light. And when crimes do happen, he says, the police come right away.

On the other side of the intersection sits another gas station — this one an Exxon with a Subway sandwich shop attached. The business does not have a Green Light.

It’s just across the street, but the clientele here seem like they’re a world apart. Multiple customers and even a worker say they don’t know what Project Green Light is. This despite the fact that there are more than 700 properties with flashing Green Lights in the city of Detroit.

I find a customer who has heard of the program, Michael Sterling. He tells me he thinks Green Light might be giving some patrons a false sense of security.

“The cameras, they don’t matter in the city. People are gonna do what they want to do besides if the cameras are there or not,” says Sterling.

“We’re in the city, in Detroit, and it’s f—– up out here,” Sterling says.

The prevention factor

According to the FBI, in 2019 the Detroit Police Department reported 280 murders. In 2020, that number rose to 328. Project Green Light started in 2016 as a potential crime intervention tool. It originally targeted gas stations since they were seen as crime hot spots but has expanded to include fast food restaurants, churches, apartment buildings and more. The video from these participating locations is pumped into a special area of Detroit’s police headquarters called the Real Time Crime Center.

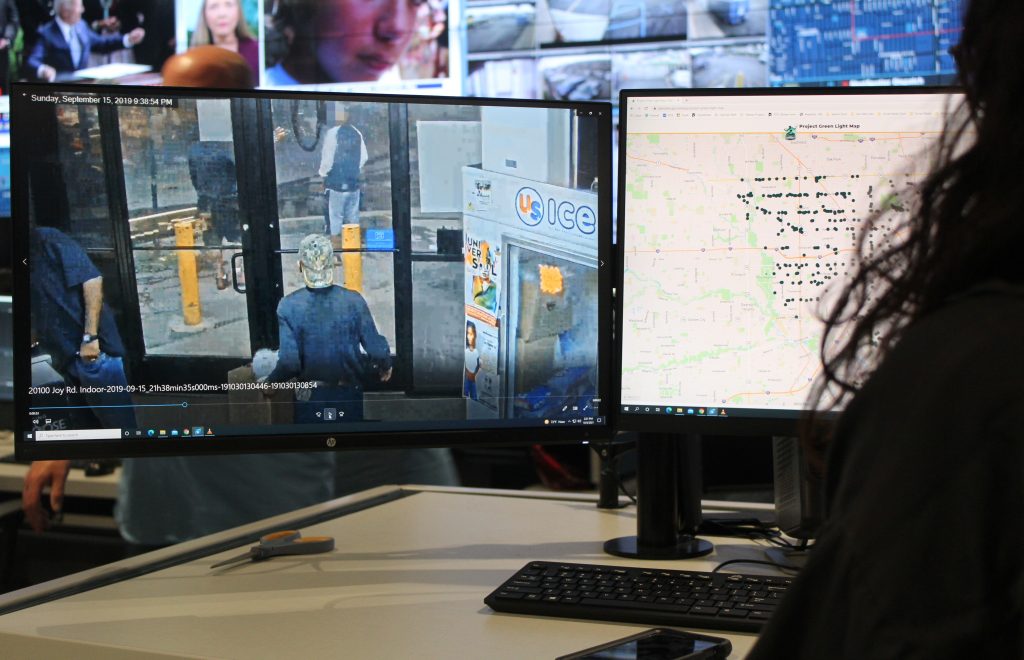

Inside, the center has a wall of screens that show footage from Project Green Light, traffic cameras, mapping technology, the local news and more. On top of that, crime analysts have monitors on their desks where they can view additional footage.

The Detroit Police Department was unable to tell me how common it is for crimes to be caught in the act. But the department says Project Green Light has multiple goals — it’s not just about stopping crime as it happens. It’s also about assisting with prosecuting crime and preventing it, too.

There’s data from the department and academics that suggests that Green Light does help with prosecution: Cases involving crimes caught on video at Green Light locations are more likely to close. But what about the prevention factor? Does Green Light help reduce crime?

“In terms of a method that’s going to definitively reduce crime, we don’t necessarily have the evidence to say that Green Light is particularly effective at that.” — Giovanni Circo, assistant professor at the University of New Haven

“Boy, so that’s a tough question” says Giovanni Circo, an assistant professor at the University of New Haven who specializes in crime analysis. He’s one of a handful of researchers who worked on a 94-page document looking into the effectiveness of Project Green Light. Some of the work he’s done was paid for by a grant to do research in partnership with the Detroit Police Department.

On the one hand, Circo says, Green Light has many positive attributes.

“From a perspective of making people feel safer, improving relationships between business owners and the police, I think that has been a good thing,” says Circo.

But he says when it comes to specifically assessing Green Light’s effectiveness at preventing crime, the question is not so easy to answer.

“In this case, we can say ‘maybe,’” he says.

The report Circo worked on found something that might sound surprising at first. If a location joined Project Green Light, crime actually tended to go up, except for violent crime, which stayed about the same. Circo says this probably reflects an increase in crime reporting rather than an actual increase in incidents occurring.

“I think for a long period of time, some of these minor crimes were just much less likely to be reported for a number of different reasons. things like staffing, for example, or a feeling among business owners that if they called the police for a minor crime, like shoplifting, that the police wouldn’t respond,” says Circo.

Despite a likely uptick in crime reporting, the study found Green Light does appear to reduce the occurrence of one specific crime: carjacking. Yet ultimately, Circo says, the report could not conclude that Green Light prevents crime overall.

“In terms of a method that’s going to definitively reduce crime, we don’t necessarily have the evidence to say that Green Light is particularly effective at that,” says Circo.

I ask the same question — “Does Green Light reduce crime?” — to a captain with Detroit’s crime intelligence unit. But I get a strikingly different answer.

“So, what we found is that for locations that have become Green Light there’s usually a lessened amount of crime that occurs at those areas,” says Captain Ian Severy.

When I ask if he can elaborate, a communications officer for the police department, Rudy Harper, who’s sitting in the room chimes in.

“So, I don’t think in the police department that we look at numbers because numbers can be manipulated at times,” says Harper.

Facial recognition technology a concern

The department’s inability to use data to support all of its claims about Green Light is just one of the reasons that it has some critics.

“I think residents need to be absolutely worried about Project Green Light,” says John Sloan, III, one of the leaders of the Detroit chapter of Black Lives Matter.

Sloan, like many activists, is concerned about how Project Green Light is used with facial recognition technology — software that identifies people from a picture.

“Facial recognition software is just largely unpredictable in its ability to take race into account. What you can predict is the ways in which it will fail people with more melanin in their skin,” Sloan says.

A 2019 study by the U.S. government’s National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) found that false positive rates for facial recognition software are highest in African and East Asian people and lowest in Eastern Europeans. In other words, facial recognition is more likely to misidentify someone with darker skin.

When I ask Captain Severy about the Detroit Police Department’s use of facial recognition with Green Light at first he says, “Project Green Light does not use facial recognition.”

That’s technically true, because Green Light cameras don’t have facial recognition embedded in them. But, Severy does ultimately acknowledge the department takes still images from Project Green Light footage and puts them into facial recognition software. So yes, Green Light footage doesn’t use facial recognition, but facial recognition uses Green Light footage.

In a notorious blunder, the software was used with images taken from non-Green Light video — regular security footage — to wrongfully arrest a suburban Detroit man, Robert Williams, in 2019. Severy says its policies have changed since then and the department now has to have evidence beyond a facial recognition software match to arrest someone.

“Facial recognition software is just largely unpredictable in its ability to take race into account. What you can predict is the ways in which it will fail people with more melanin in their skin.” — John Sloan III, one of the leaders of the Detroit chapter of Black Lives Matter

While facial recognition gets a lot of attention, it’s just one of the things that activists take issue with in regards to Project Green Light. Another concern is the surveillance aspect of the program.

“There’s a reason we require the police to have reasonable suspicion or probable cause before they go interfering with people,” says Eric Williams, an attorney who works with the ACLU of Michigan and the Detroit Justice Center.

Detroiters are allowing themselves to be surveilled in real time when they go into Green Light businesses under the premise that doing so will make their lives safer. But, Williams reiterates there’s no strong evidence that Green Light reduces crime overall.

“It’s an expensive toy that doesn’t really accomplish a whole hell of a lot other than, you know, place a burden on store owners to buy bandwidth and a burden on taxpayers to support the Real Time Crime Centers to build them and staff them,” says Williams.

He would like to see the center done away with. But that’s not likely to happen. It’s a crown jewel in Detroit’s public safety headquarters and the department shows no sign of shutting it down.

Project Green Light, at least for now, will persist. Some Detroiters will continue to go out of their way to fill up their gas at stations with flashing Green Lights, believing that doing so will keep them safer. Other residents will continue to go to whatever gas station is closest, not buying into the premise that surveillance could save their life. The police will likely continue to applaud the program event though there’s little documented evidence that it reduces crime overall. And all the while surveillance will continue to increase in the Blackest city in America.

In this episode:

- WDET’s Laura Herberg investigates the Detroit Police Department’s claims that Project Green Light improves public safety in the city.

- Detroit residents and business owners share their impressions of Project Green Light

- A glimpse inside Detroit’s Real Time Crime Center

- Eric Williams of the Detroit Justice Center

Related posts:

- Tracked and Traced: How thousands of American Muslims ended up on the terrorist watch list

- What Are Those Flashing Green Lights Doing on Detroit Businesses?

- Greektown Businesses Install Security Cameras on Streets

Tracked and Traced is supported by the Pulitzer Center, the Community Foundation for Southeast Michigan, and MSUFCU.

Trusted, accurate, up-to-date.

WDET strives to make our journalism accessible to everyone. As a public media institution, we maintain our journalistic integrity through independent support from readers like you. If you value WDET as your source of news, music and conversation, please make a gift today.