Detroit Black Farmer Land Fund Launches Second-Year Crowdfunding Campaign

The project is the collaborative effort of several longtime figures in the city’s urban agriculture community, and aims to get land back into the hands of Black Detroit farmers and gardeners.

Rooted shares stories about land tending, community healing and regeneration happening right here on the ancestral land of the Indigenous Anishinaabe, the area commonly referred to as Detroit.

As the Detroit Black Farmer Land Fund launches its crowdfunding campaign for the second year, three of the co-founders reflect on food sovereignty, land access and ownership and ancestral knowledge in the context of this work.

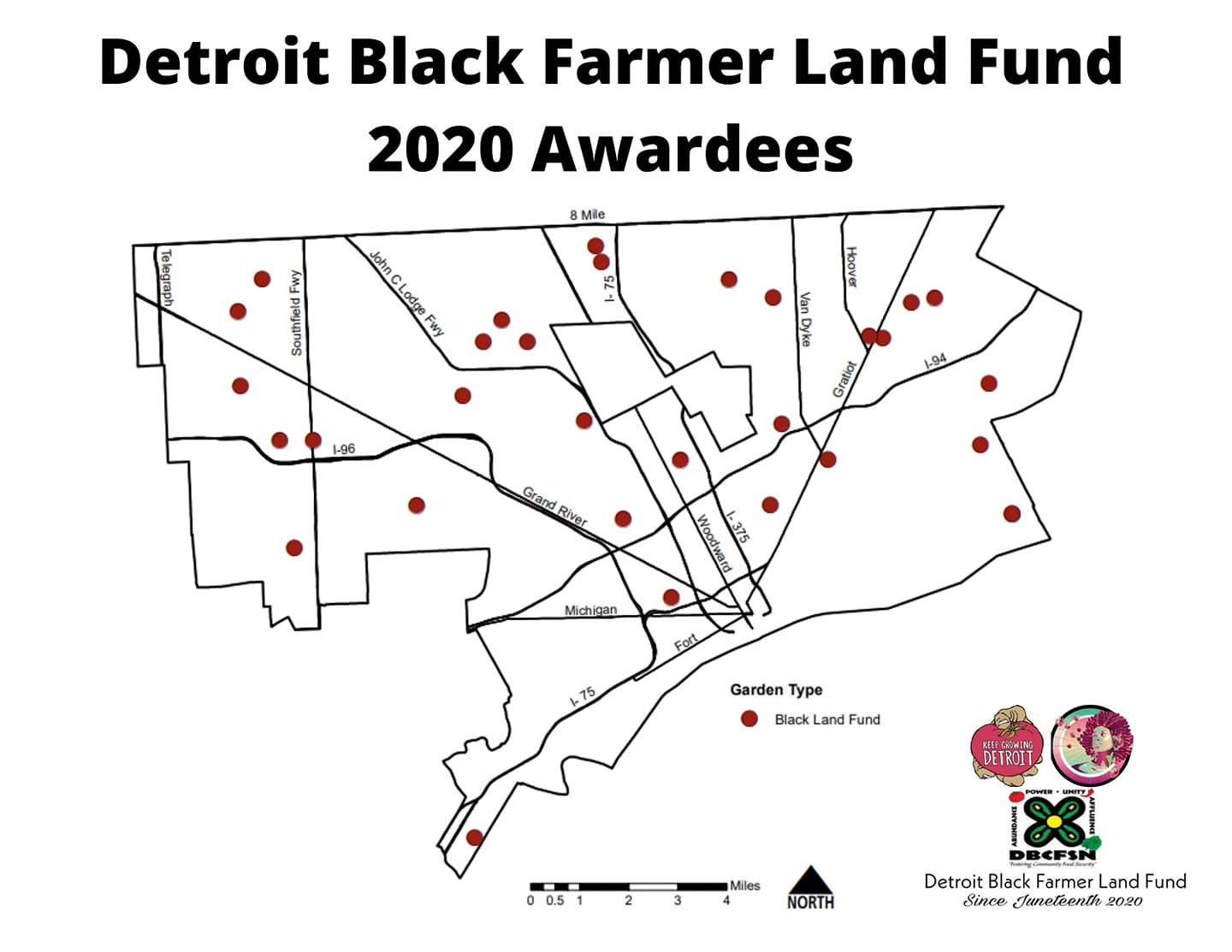

Annamarie Sysling went to Oakland Avenue Urban Farm in Detroit’s North End and talked with three of the directors of the Detroit Black Farmer Land Fund, which raised more than $60,000 last year used to get land into the hands of 30 African American farmers and gardeners in Detroit. This year, they’re hoping to raise enough to award funds to 40 Detroiters.

There are four co-founders of the Detroit Black Farmer Land Fund: Tepfirah “Tee” Rushdan, co-director of Keep Growing Detroit; Erin Preston-Johnson Bevel, who is a board member of the Detroit Black Community Food Security Network; Jerry Ann Hebron, who is the executive director of the North End Christian Community Development Corporation and project manager of Oakland Avenue Urban Farm; and Dr. Shakara Tyler, who is the board president of the Detroit Black Community Food Security Network.

“You have people coming in with capital … and these people don’t look like us, so they’re able to access land, access housing … and here we are, been here holding things down.” –Jerry Hebron, Detroit Black Farmer Land Fund

Rushdan describes the Black Farmer Land Fund as “a fund for Black farmers to purchase land in the city.” She says it was a struggle to get this dream off the ground for several years. But, after the events of last summer, which included uprisings and protests calling for social and racial justice amid the pandemic, the group decided the time had come to get the project up and running. They launched the crowdfunding campaign on Juneteenth of last year, and to put it simply, the community responded in a big way.

A Community Cause Emerges Amid the 2020 Pandemic Summer

“Within a couple hours, we hit the $5,000 mark and we were like where do we go from here? From there we just opened it up … and the community really turned out for this project. We were able to raise $65,000 in a matter of a few weeks,” recalls Rushdan.

Out of around 60 applications, the group was able to award funds to 30 people. But of those 30, just a handful have been able to successfully navigate the land acquisition process through the city. There are a lot of steps in the process, and according to Rushdan, the delays have come from both the gardeners and the Detroit Land Bank, but ultimately she’s hoping the bureaucratic workflow will become more streamlined and accessible as time goes on.

Addressing Systemic Inequity

Co-founder Jerry Hebron says it took her own organization a long time to become the legal owners of the land that is now home to Oakland Avenue Urban Farm.

“It took 15 years and the approval of the urban agriculture ordinance, which took two years, for us to get the first purchase agreement signed,” says Hebron. She also points out the difficulty of navigating the city’s current infrastructure around land acquisition and how it fits into the bigger picture of historic inequity that has kept Black Americans from stability when it comes to land acquisition and ownership. Hebron and the other co-founders of the fund hope their fund will play a role locally in repairing the effects of decades-long systemic wealth extraction from the Black community.

Lending practices, land ownership policies and violence have all negatively impacted the national picture of Black farming in the United States. In fact, earlier this year The New York Times reported that “farms run by African Americans now make up less than 2% of all of the nation’s farms, and that’s down from 14% in 1920.”

And for Hebron, whose family had land in Tennessee for generations, this is personal as she recounts her own family’s story around these unfair policies. “My grandfather was run off his land, which meant that my family had to leave Tennessee … and this had happened around the country to so many families,” she says, adding that this was not only an extraction of wealth but also a disruption to the general financial and social welfare of her family. Now in Detroit, she says this inequity is still playing out from her view as it relates to access. “You have speculative development going on. You have people coming in with capital … and these people don’t look like us, so they’re able to access land, access housing … and here we are, been here holding things down. We don’t have the capital and we can’t navigate the system,” says Hebron.

Reclaiming Health and Reimagining Land

Now, as Detroit’s post-1950s automotive boom continues to fizzle out, Hebron says the vacant land carries with it an opportunity to reimagine the city in a way that repurposes the land and empowers historically disenfranchised residents. After more than a decade of working in the North End, Hebron says she and others in the community were finally able to demonstrate that growing food, hosting a weekly seasonal farmers market and installing outdoor art and garden infrastructure are viable and legitimate sources of economic viability in Detroit.

On the precarity of tending land without owning it for 15 years, Hebron acknowledges it wasn’t always easy. “It was hard to come to work, you know, but we had a responsibility to the community. And so we came every day, and used the strategy of ‘OK, higher and best use?’ Well in the meantime, I’m gonna put some artwork out here. I’m gonna put a water catchment system out here — capital improvements — I’m staking my claim,” she says.

“When COVID and the uprisings were happening last summer it became clear this has to end now, we can’t continue to wait to see the changes in our communities we want to see.” — Erin Preston-Johnson Bevel, Detroit Black Farmer Land Fund

In thinking about the health disparities that disproportionately impact Black Americans, co-founder Erin Preston-Johnson Bevel says it can be a challenge to simultaneously address long-term systems change and these urgent issues. She says the COVID-19 pandemic brought that reality into stark relief in Detroit. “The food insecurity we had already been working for years to combat was put on display even more,” says Bevel. However, she also points out that these health disparities becoming so apparent during the pandemic, illustrated how food cultivation and gardening can be such important tools for liberation within Detroit’s Black community. “It’s our ancestral birthright … a piece of our liberation,” says Bevel, who notes that “a lot of people say you can go to court and change laws … I call myself a recovering lawyer … but those things will take 10 years or more … those things are long term … when COVID and the uprisings were happening last summer it became clear this has to end now, we can’t continue to wait to see the changes in our communities we want to see.”

Remembering An Ancestral Birthright

Bevel notes that in addition to improving health outcomes and community empowerment, this work is also deeply healing and has a ripple effect that ensures traditional knowledge systems around land tending will be passed down to future generations of Black Detroiters. “In the African tradition we are always thinking about intergenerationalism,” she says pointing to the Sankofa philosophy from the Akan tribe in Ghana. According to a definition from Berea College, a literal translation of Sankofa is “it is not taboo to fetch what is at risk of being left behind.”

Bevel points to Leah Penniman’s “Farming While Black,” in which Penniman recounts an incredible story of African ancestors boarding ships with seeds braided in their hair, demonstrating their faith that a future generation would exist and persist against all odds. “They were thinking about us,” notes Bevel who adds that reviving and honoring these ancestral memories and traditions can be powerfully transformative in communities in Detroit and beyond. Bevel says she is thinking about not just the next generation, but several generations down the line, and she sees other gardeners thinking in a similar way.

One awardee from the 2020 fund is showing kids in his community how to garden. “He doesn’t have to grow food for anyone else but he wants to the kids in his community … the discipline of farming.” She says that this particular awardee stresses to the young people in his neighborhood that if you can grow your own food, you will be disciplined enough to do anything.

Rushdan, a mother of four, shares this sentiment and explains that she views herself as a member of the middle generation. “We’ve got the elders, and the youth and I think it’s up to me to make sure this transmittal of knowledge happens,” she says. Meanwhile Hebron remembers being taken down south each year after the school year ended. She recalls going into the fields to play with the animals and watching her elders harvest food and slaughter animals for meat. “I didn’t process it until I was an adult … there was a reason they got us out of the city … my parents wanted us to see where our food came from, how it was processed and we also had responsibilities,” she says. Hebron says this intergenerational aspect of gardening is very important and started for her when she was a child. Now, as she prepares to welcome a new group of Detroit kids to come work at Oakland Avenue Farm for the summer, she’s excited to watch the ways that skillsets acquired in a garden end up preparing young people for so many aspects of life.

“When we come back to the land, there’s such a relief that maybe people don’t expect,” says Bevel, “of course its hard work … but you develop a new understanding of the symbiotic relationship between us and the earth.”

Get Involved with the Black Farmer Land Fund

Check out all of the work being done by the organizations behind the Detroit Black Farmer Land Fund

Subscribe to the Detroit Black Farmer Land Fund YouTube Channel

Trusted, accurate, up-to-date

WDET is here to keep you informed on essential information, news and resources related to COVID-19.

This is a stressful, insecure time for many. So it’s more important than ever for you, our listeners and readers, who are able to donate to keep supporting WDET’s mission. Please make a gift today.