Street Outreach Court Detroit Brings the Courts to the People at Eastside Soup Kitchen

Capuchin Soup Kitchen is more than just a place to get a hot meal. It’s also aims to address the root causes of social injustice.

This report was produced in collaboration with Feet in 2 Worlds, a journalism fellowship focused on the intersection of food and community. Listen to the full audio piece produced by Dorothy Hernandez by clicking on the player above.

More than 600 meals are served every day at the Capuchin Soup Kitchen on the east side of Detroit. On a recent Thursday, volunteers serve guests pepperoni pizza and salad with their choice of milk or juice. But the soup kitchen is more than just a place to get a hot meal.

Once a month it hosts a traffic court. Street Outreach Court Detroit is a mobile courtroom that was established to help homeless people get their licenses back, so they can get to work and put their lives back together. Since 2012, more than 400 people have been given a second chance to drive legally through Street Outreach Court Detroit.

In Detroit if you can’t drive it’s hard to earn a living. Long commutes are common, and public transportation is unreliable or unavailable. It’s especially tough for people who have lost their driver’s license, which can lead to losing jobs, mounting bills, and, in the most extreme cases, losing homes. Part of the Capuchins’ mission is to address the root causes of social injustice, and the traffic court plays a role in that effort.

“The reason we host it here is because a lot of our people won’t go down to the courts,” says Brother Ed Conlin, a chaplain at the soup kitchen. “They’ve been arrested, they’ve been set up, they’re afraid, and they’re even afraid to go to the hospital if are they get mugged or hurt because they’ll get arrested.”

“This gives them the chance to trust us,” says Conlin. “They trust us in the kitchens and the courts recognize that.”

Court is in session

Judge Adrienne Hinnant-Johnson of the 36th District Court presides over the makeshift traffic court today. The judge will hear 15 cases, all are homeless men.

Many of them are unable to drive because their license was taken away. One man rode his bike from Wyoming and Fenkell, a 22-mile round trip, in the middle of February in below freezing weather.

Each defendant takes a seat between his caseworker and defense attorney Charles Hobbs, a lawyer with the group Street Democracy.

Hobbs presents evidence to the court, including testimony and documents that show each defendant has successfully completed a work plan. This typically includes community service, applying for food assistance and enrolling in job training. The plans are aimed at tackling the root causes of homelessness.

License for freedom

Each defendant has his own story of struggling to live in Detroit without a driver’s license.

Terry Scott is studying to become a barber after 17 years of incarceration. He’s looking forward to regaining his independence.

“I’m just trying to get my life back, clear up what I need to clear up and be a good father,” says Scott.

Gerald Wilson is a chef with Sodexo, a food service company. Wilson grew up cooking with his mom who taught him the importance of cooking from scratch and buying fruits and vegetables from the farmers market. Without a license, his commute is three hours, waking at 2:00 am and catching three buses to make it to work by 6:30 am.

Wilson hasn’t had a license for 10 years, and he’s racked up nearly $5,000 worth of traffic tickets. He didn’t make enough to pay off his debt, and he was scared of going to court. If he could drive, Wilson says, he’d be able to launch his own catering service.

“When you’re going through all of this and you kind of feel like, does anybody care? Is there anybody out here that’s concerned about me? Because you have all of these things coming against you,” says Wilson.

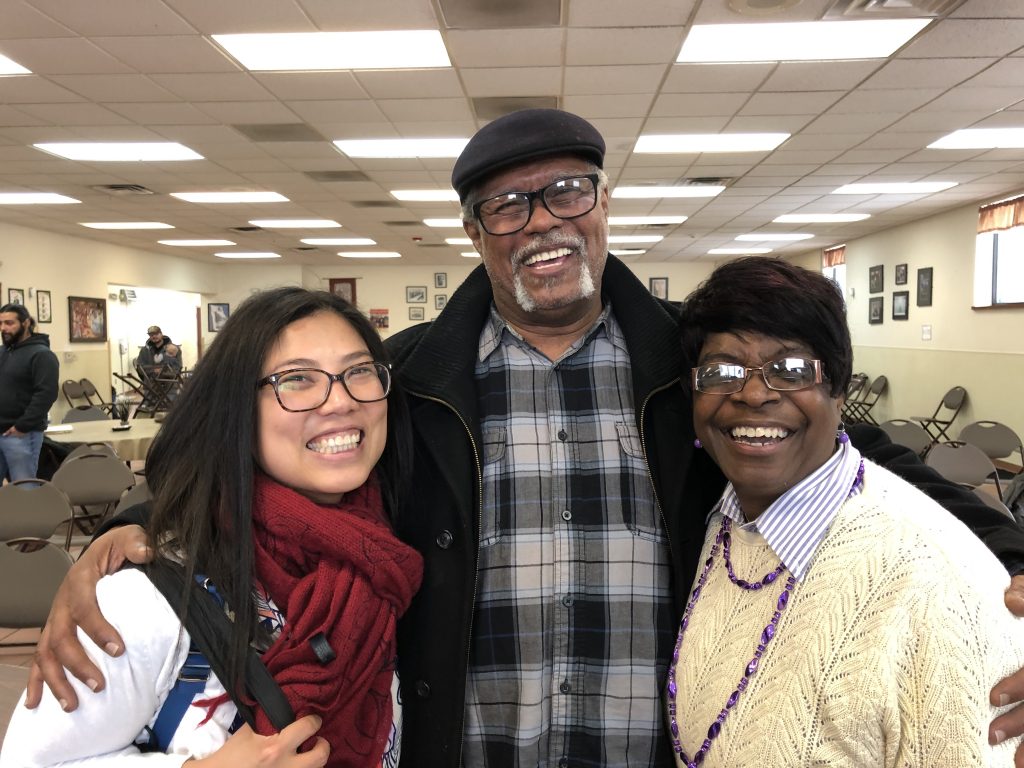

Clark Washington was once homeless. Now he helps run the program. For him it’s not just about helping people in need. It’s about supporting Detroit as the city tries to bounce back from bankruptcy and years of neglect.

“That’s the only way we’re going to bring the city back, bringing people back with it,” says Washington. “We get the people back on their feet, we can get the city back cause we’re not giving up on it.”

Judge Hinnant-Johnson grants the defendant counsel’s motion, reinstating the defendants drivers licenses and waiving any associated court fees. The courtroom breaks out in applause.

With their cases closed, people who appear before the court can move on to rebuilding other parts of their lives. Some will reconnect with families, others will get the job that they’ve been hoping to land. And for some having a license means no longer having to ride a bike for miles on snowy city streets to get to a very important appointment.

Food, Borders and Belonging explores food in Detroit from the perspective of immigrants and journalists of color. Inspired by the Feet in 2 Worlds Food Journalism Fellowship at WDET, this series of stories looks at the role food plays in the transformation of city neighborhoods and in defining identities. Read more here.