CuriosiD: Are There Salt Mines Under Detroit?

Pat Batcheller May 15, 2017Yes, but other than miners, few people have ever seen the inside of them.

Local governments use rock salt in the winter to melt ice on the roads. You knew that already. What you might not know is that some of that salt comes from beneath the roads themselves.

Detroit and much of the Great Lakes region sit on top of a prehistoric salt deposit, the remains of an ancient sea.

How did it get there?

The salt formed about 400 million years ago, when a shallow basin covered what is now Michigan. Wayne State University geology professor Sarah Brownlee says the basin was similar to the body of water we know as the Red Sea.

“It’s a shallow sea that’s somewhat connected, but mostly disconnected from the ocean,” Brownlee says. “So when the sea water spills into the basin, it eventually evaporates away, leaving behind the salts that are dissolved in the water.”

Over time, layers of earth built up over the salt, which now lies about 1,100 feet below the surface. It lay undisturbed until the early 20th century, when a mining company first attempted to build a shaft in southwest Detroit. Since 1910, several companies have owned and operated the mine. A Canadian company, the Kissner Group, bought it in 2010, and does business as Detroit Salt Company.

A city beneath the city

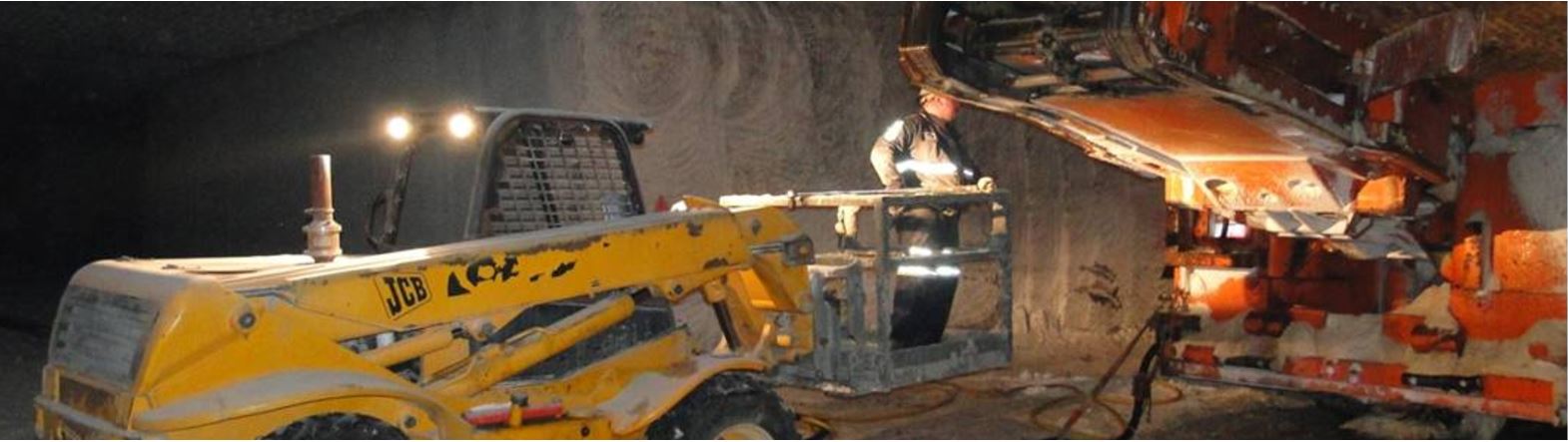

Though few people besides miners have actually seen the inside of the mine, photographs reveal a network of roads, or causeways, some as wide as the thoroughfares on the surface above. These roads run underneath parts of Detroit, Melvindale, and Allen Park, transporting workers and machinery throughout the mine. One may wonder how all that heavy equipment gets down there. “Piece by piece,” says George Davis, who manages public affairs and public safety for Detroit Salt Co.

“We take them apart and bring them down in what’s called a ‘skip’, what people normally see as an elevator, and then reassemble it down there at the bottom,” Davis says.

It’s a one-way trip. Davis says once the machines are put back together, they stay inside the mine, extracting and processing salt.

“We use a machine called a continuous miner, which is an augur that grinds against the wall of salt,” Davis says. “It’s thrown back and brought by conveyor belts to a crushing and screening place, where we break it down to the right small size, bring it back up, and ship it to road commissions for winter de-icing.”

You’re driving on it

Road salt is Detroit Salt Co.’s primary product. Two of its main customers are Wayne County and the City of Detroit. Mayoral spokesman John Roach says for the winter of 2016-17, the company sold 9,000 tons of salt to the city, with a commitment to deliver another 16,000 tons when the next winter starts. Wayne County’s Department of Public Works Roads Division purchased more than 44,000 tons of Detroit salt. It also bought more than 20,000 tons from the company’s main competitors, Compass Minerals and Morton Salt, which have mines in Ontario. Morton runs two salt mines in Windsor and has an office in Detroit, where it once stored salt on a slab next to the Rouge River. The slab is empty, however, and the property appears to be unoccupied (a Morton spokesperson did not return WDET’s calls for this report). Compass Minerals was the primary salt vendor for Oakland and Macomb counties this past winter.

Salt is a competitive industry

The road commissions’ need for salt varies each winter, depending on how much snow and ice fall. If the weather is good, business tends to be bad. The Detroit salt mine ran continuously for 73 years until 1983. Stiff competition, mild weather, and difficult economic conditions forced the mine’s owner at the time, International Salt Co., to cease mining operations. The company sold the property to Crystal Mines in 1985. For the next several years, there were discussions about turning the mine into a storage facility for hazardous waste. Those plans never materialized, and in 1997, the mine changed hands again when Crystal Mines sold it to the Detroit Salt Company. Mining resumed in 1998, and Kissner Group took over in 2010.

Is it safe?

Mining of any kind is generally risky, but the Detroit Salt Company’s George Davis says worker safety is paramount.

“We train our mining crews and focus them on the idea that we all want to go home at the end of the night. We continuously train,” Davis says.

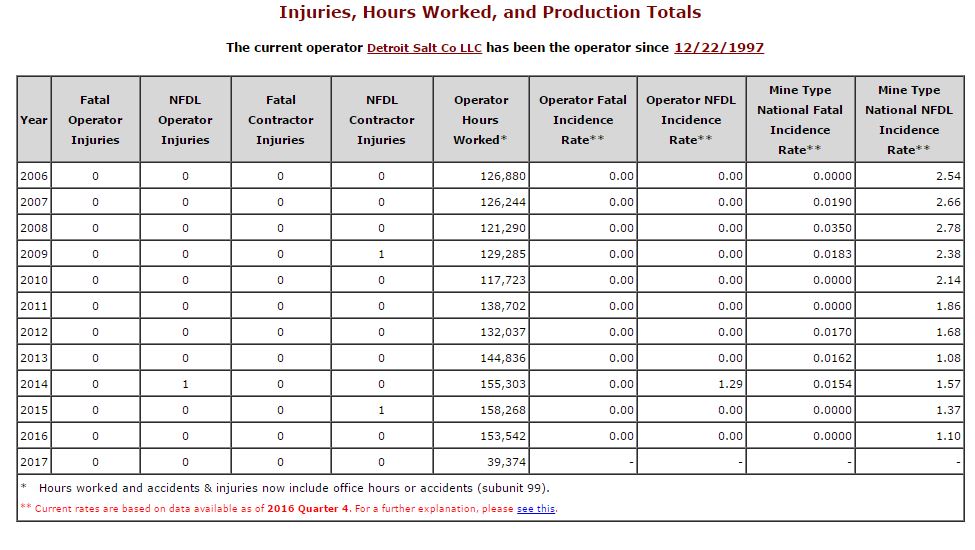

Those efforts appear to be effective. According to the U.S. Mine Safety and Health Administration, there have been three injuries reported by Detroit Salt Co. since 2006, the most recent occurring in 2015. This has given the company one of the lowest incidence rates among all mines of its kind. The last known fatality at the mine happened in 1983, when a worker fell down the shaft.

George Davis says training is critical, but a little divine intervention doesn’t hurt, either. A statue of St. Barbara, the patron saint of miners, watches over the crews as they come and go. Davis says the company believes salt is a resource that comes from the Lord.

“He provides it for our daily use and benefit,” Davis says. “We want to encourage the faith of our workers and their families so they’re safe and secure.”

The company uses a method of mining called “room and pillar”, in which machines alternately dig out one column of salt, leaving another behind, and so on. Davis says this supports the roof of the mine, and requires no blasting.

A look inside

The International Salt Co. offered public tours in 1983 as a way to make money while the mine was inactive. These stopped in 1985 when the company sold the mine. George Davis says Detroit Salt Co. doesn’t offer public tours today, because it would interrupt production. The company does maintain a web site with information about the mine and its history. Davis also speaks to schools and community groups. He says one question comes up often.

“Can we eat the salt?”

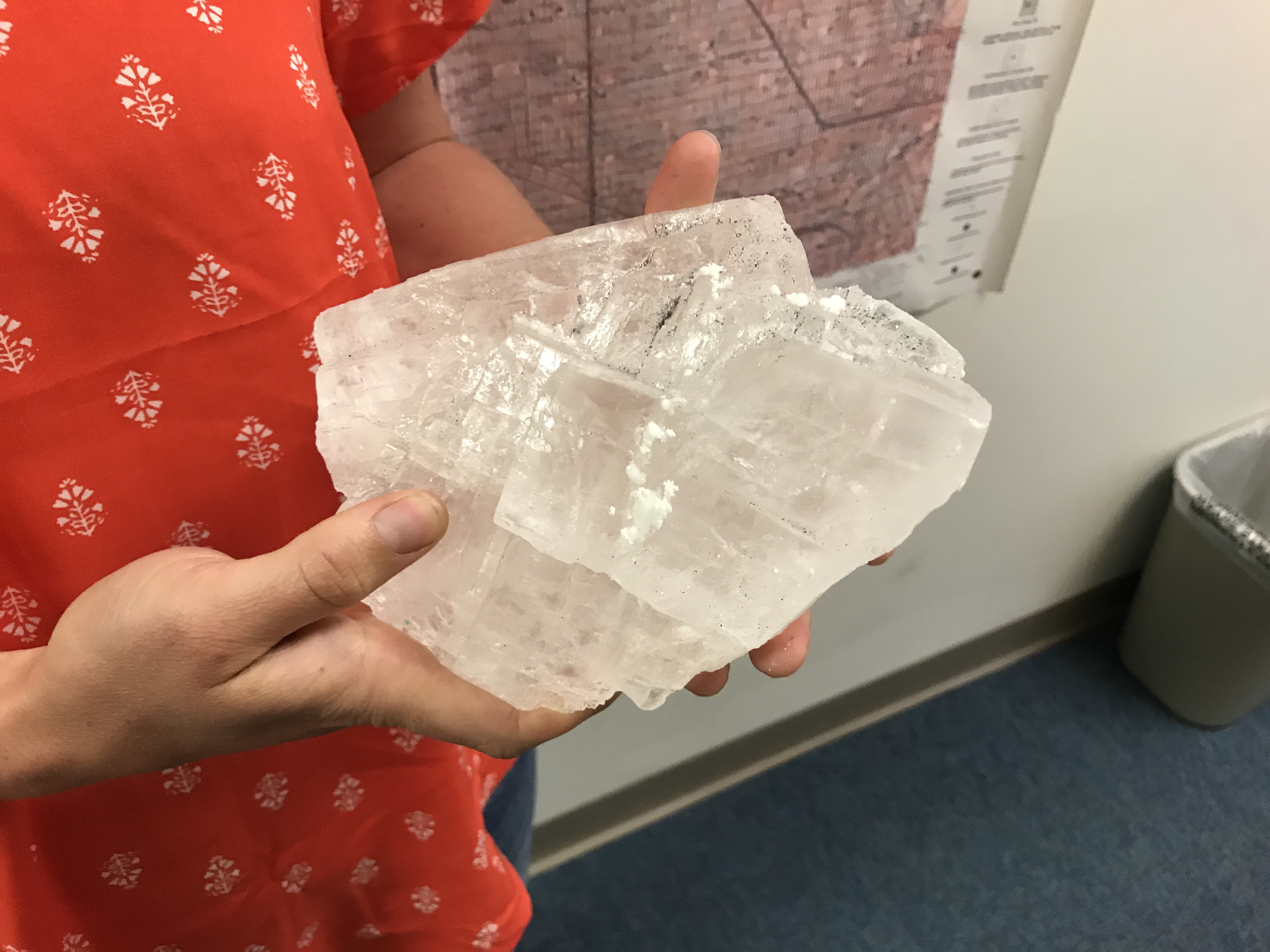

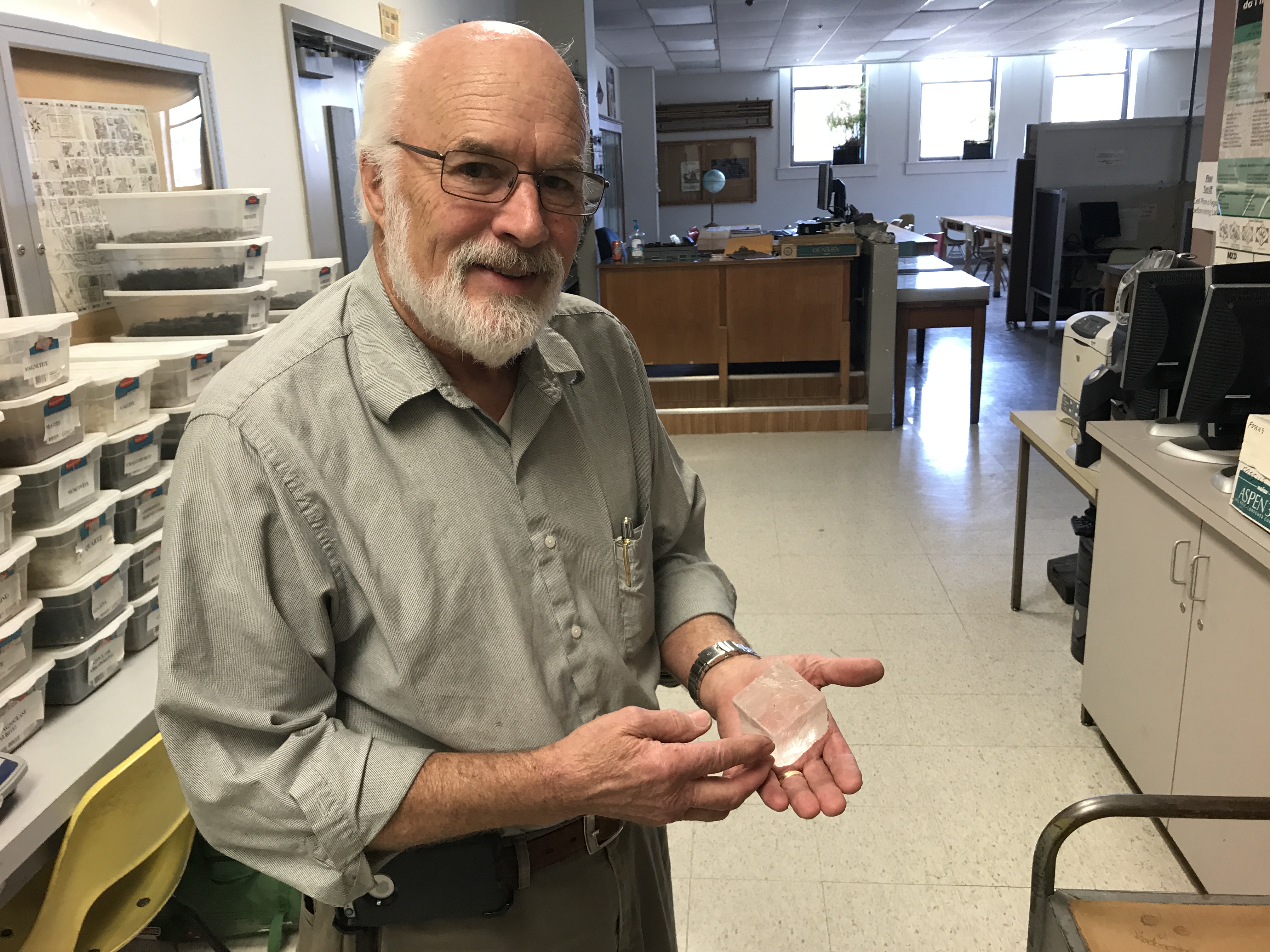

The short answer is no, although there’s no difference between the chemical composition of rock salt and table salt. Wayne State University geologist Dave Lowrie says the salt beneath Detroit is “remarkably pure.”

Lowrie says he has been inside the mine and has brought back samples to use in his classes and labs.

“It’s very clean, very dry, it’s kind of fun,” Lowrie says. “You take a flashlight, hold it against the wall, and you can see light disappearing into this nice, clear salt.”

Music of the mines

While the mine is not open to the public, one can use their minds to imagine what it looks like.

Such a vision inspired Ann Arbor composer Paul Dooley to write “Salt of the Earth” for the Detroit Chamber Winds and Strings in 2012. Dooley, who teaches at the University of Michigan, says the inspiration came from stories his grandmother told him about the salt mines, and from pictures taken by award-winning photographer Tony Spina.

“I used one of (Spina’s) photos for the cover, this great photo of a man standing on a bridge overlooking a long cave, and there’s a conveyor belt of salt running through the cave,” Dooley says.

MORE: Salt Mines Inspire Local Composer

That picture, and many others, are part of the digital collection at Wayne State’s Walter P. Reuther Library.

The future

Detroit Salt Co. does not share details of its business publicly, but some information about the company is public. It has applied for a permit from the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality to increase its rock salt production rate limit from 1.7 million tons of salt per year to 2.5 million, and to install and operate a bagging system for rock salt. MDEQ says it will review all public comments before granting or rejecting the permit.

MDEQ Project Summary, Detroit Salt Co. Permit by WDET 101.9 FM on Scribd

ASK YOUR QUESTION

ABOUT DETROIT OR THE REGION

WDET’s CuriosiD is sponsored by the Michigan Science Center.