CuriosiD: Why Doesn’t Detroit Have A Subway Or Elevated Rail?

Pat Batcheller August 22, 2016City leaders talked about it for years, but it never materialized.

Bus Rapid Transit may be in Detroit’s future, but elevated rail or a subway probably are not. In this episode of WDET’s Curiosi-D, listener Andrew Parkanzky of Troy asked why there is no subway or elevated transportation in Detroit, and whether it was determined before or after the rise of the auto industry.

It turns out Detroit could have had both modes of transit a century ago. Detroit Historical Society Senior Curator Joel Stone says city leaders considered two plans in 1915.

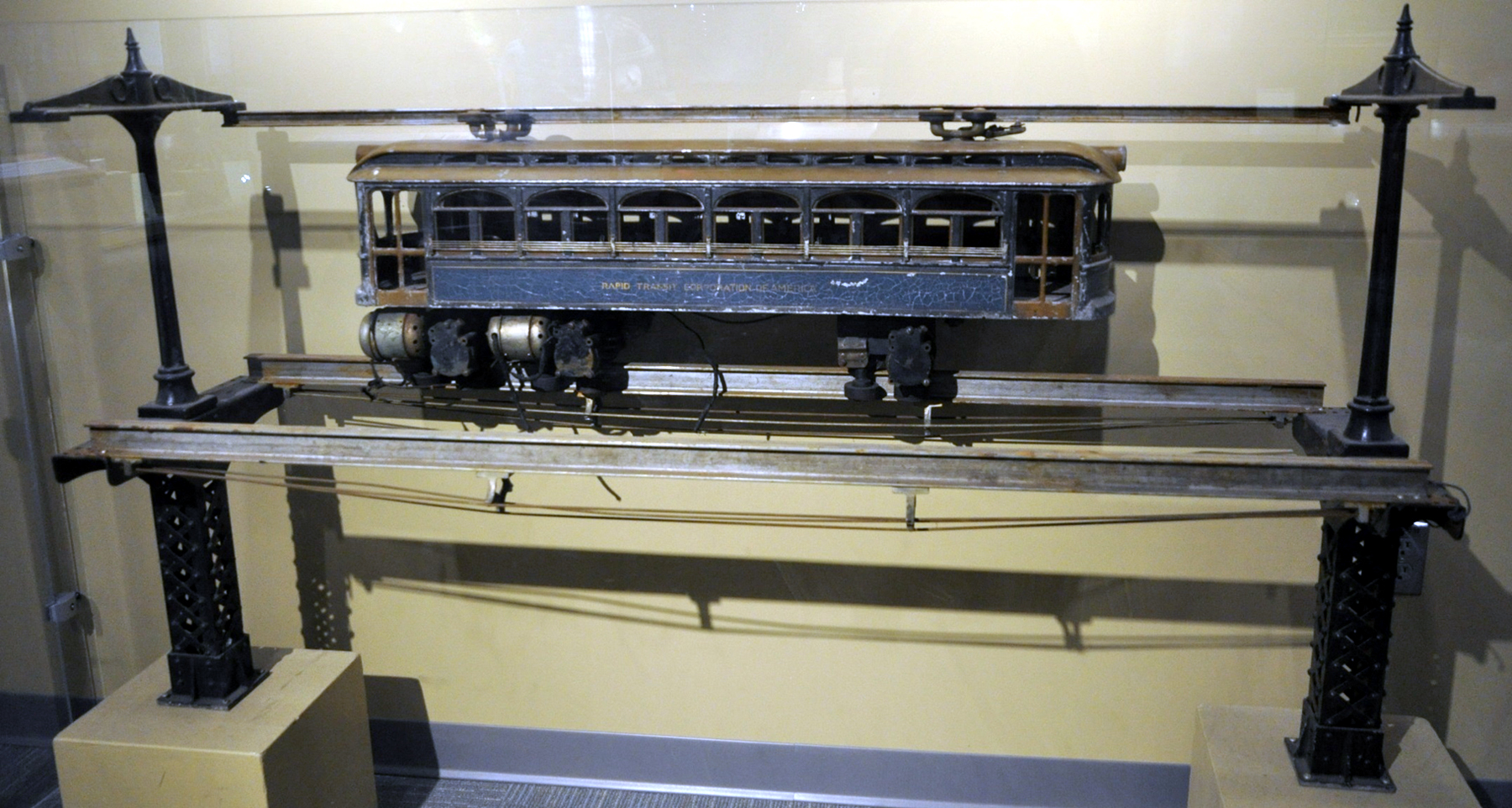

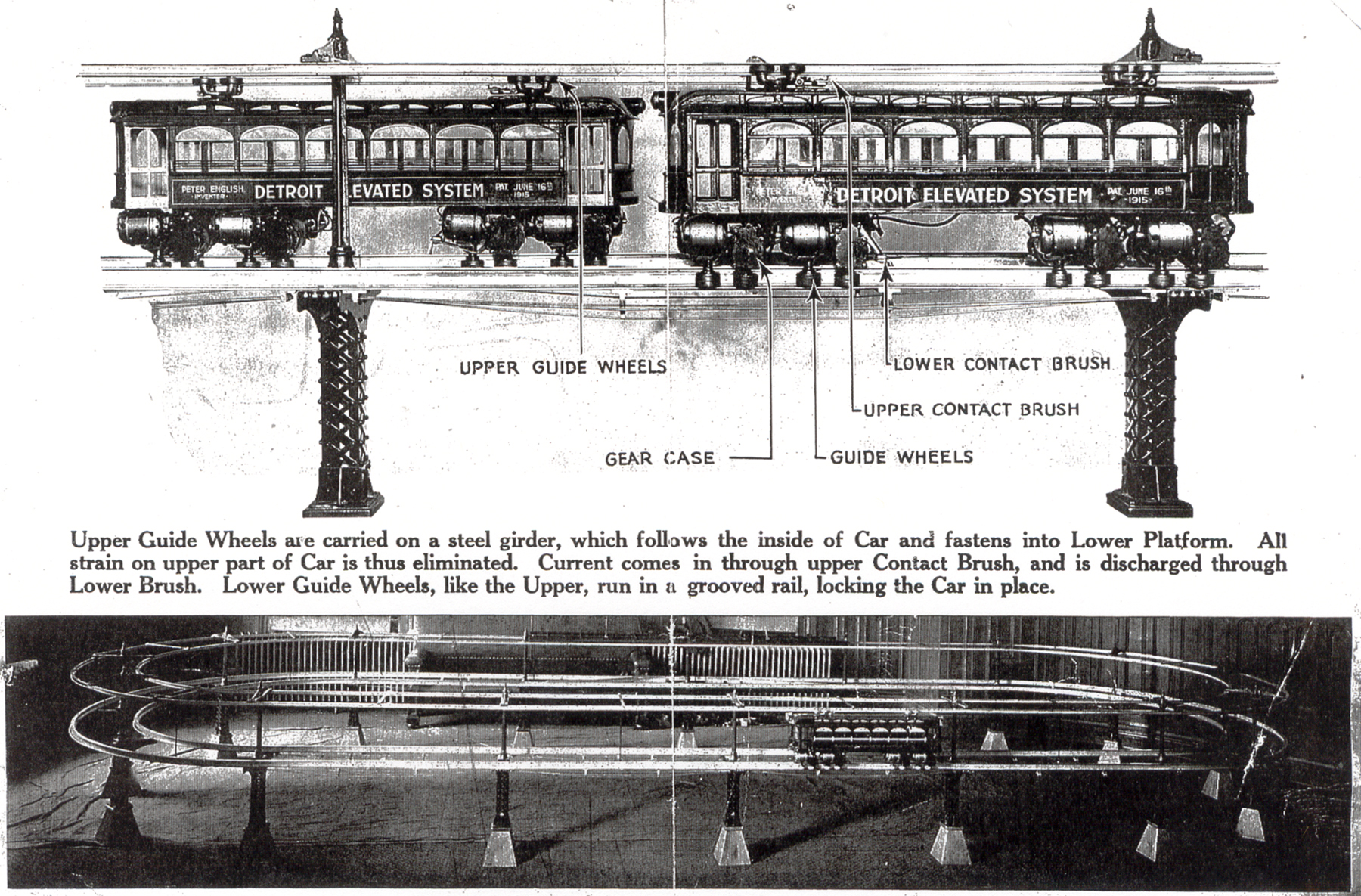

“One was for an elevated rail that would have been an electric system that was proposed by a private company that was putting it out called The Detroit Elevated System. They actually put together a working model of this which they set up in the city council chambers and showed off to them,” Stone says.

The other plan was for a subway based under what is now Campus Martius. Detroit already had one of the busiest streetcar systems in the country in the early 20th Century, and Stone says the way the city’s streets were laid out would have made subway and elevated rail service practical.

“One of the reasons why as you drive up Gratiot or Woodward, all of a sudden you get to boulevards. The boulevards were created to support an elevated rail system that would have run down the middle of those streets,” Stone says.

Such a system might have looked a lot like Chicago’s elevated rail line.

The Chicago Transit Authority says on an average weekday more than 760 thousand passengers ride the “L”, which runs from the Loop downtown to the suburbs and the city’s two big airports, O’Hare and Midway. That’s a lot of people. Of course, the Motor City’s population is smaller than the Windy City’s. But in 1915, Detroit and the auto industry were booming. Forty years before Detroit’s first urban freeway–the Davison–was built, city leaders needed a way to move people around efficiently. So what happened? The Detroit Historical Society’s Joel Stone says politics got in the way.

“Well, most of those things ran into the same problem that surface street cars had. There was constant fighting starting in the 1880s, 1890s, between private firms and people like Mayor [Hazen] Pingree, who wanted it to be a public entity,” Stone says.

The streetcars operated into the 1950s. That’s when two things happened: Detroit’s population peaked, and the Interstate System was built, giving people easier access to the suburbs. By that time, Detroit’s car culture was firmly established. Detroit Free Press business columnist John Gallagher says local governments and entrepreneurs seized the opportunity.

“Road builders building hundreds of miles of new roads and all the suburban townships and villages wanting that tax base that came with a car, a car type of culture, and so I think that all the other transportation systems, the streetcars, began to fall by the wayside because of that,” Gallagher told WDET Detroit Today Host Stephen Henderson.

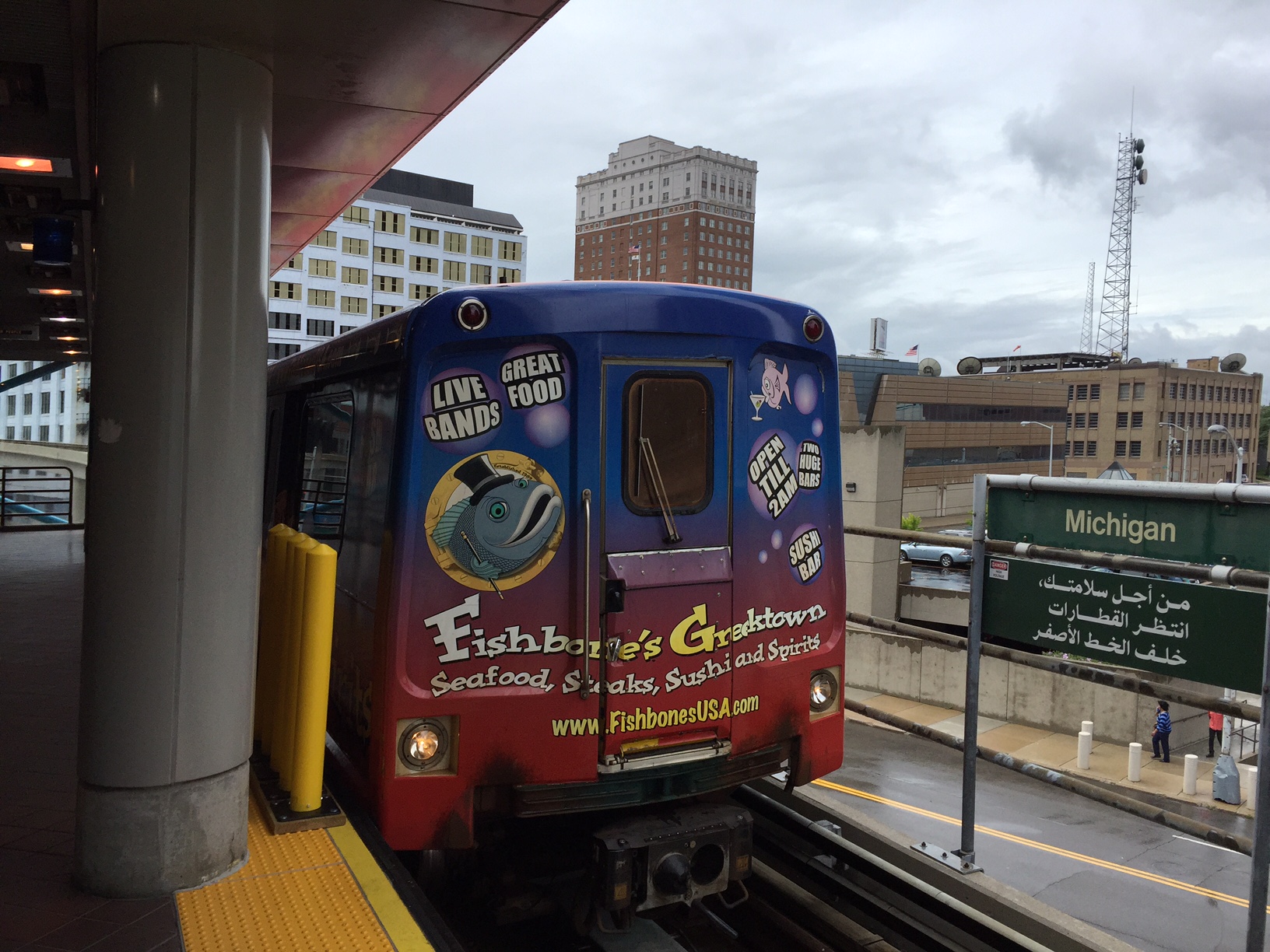

But the idea of a Detroit subway system was revived again in the 1970s when Congress created the Urban Mass Transportation Administration. President Gerald Ford pledged $600 million to cities that could build “people movers” to connect passengers to regional transit. And that’s where the Detroit People Mover came from.

The People Mover was originally built to connect Detroit to the suburbs through a series of rail lines above and below ground. To make a long story short, city, state, and suburban leaders couldn’t make a deal on regional transit, the federal money went away, and what Detroit ended up with was a closed 3-mile loop carrying passengers around downtown. The Detroit Transportation Corporation, which runs the People Mover, says ridership rose to more than 2.4 million in 2015, the highest number since 2001. That figure could grow once the People Mover is connected to the new Q-LINE streetcar route on Woodward Avenue.

In November, voters in four counties will decide whether to fund a new Regional Transit Authority, which is based around Bus Rapid Transit. As voters consider the transit tax, listener Andrew Parkanzky ponders the opportunity Detroit missed by not building a subway or elevated rail.

“I always wondered how much better the city would be if we would have had something like that,” Parkanzky says.

Andrew, we may never know.