The Intersection: Detroit’s Jewish Lawyers and Their Civil Rights Efforts

Detroit’s Jewish News reports how community’s attorneys furthered social justice work, post-1967.

One of the threads in the fabric of Detroit’s post-1967 narrative includes the civil rights attorneys who not only represented people held or charged during the uprising but then spent their careers promoting values of social justice and equity.

As part of the Detroit Journalism Cooperative’s work on the project “The Intersection,” Jackie Headapohl explored some of the stories of such lawyers in her piece in the Detroit Jewish News. “They remained very active in civil rights and justice issues. They were integral in the Jewish community’s response to the riots at that time and what the Jewish community did as a whole to address some of the discriminatory practices,” she says.

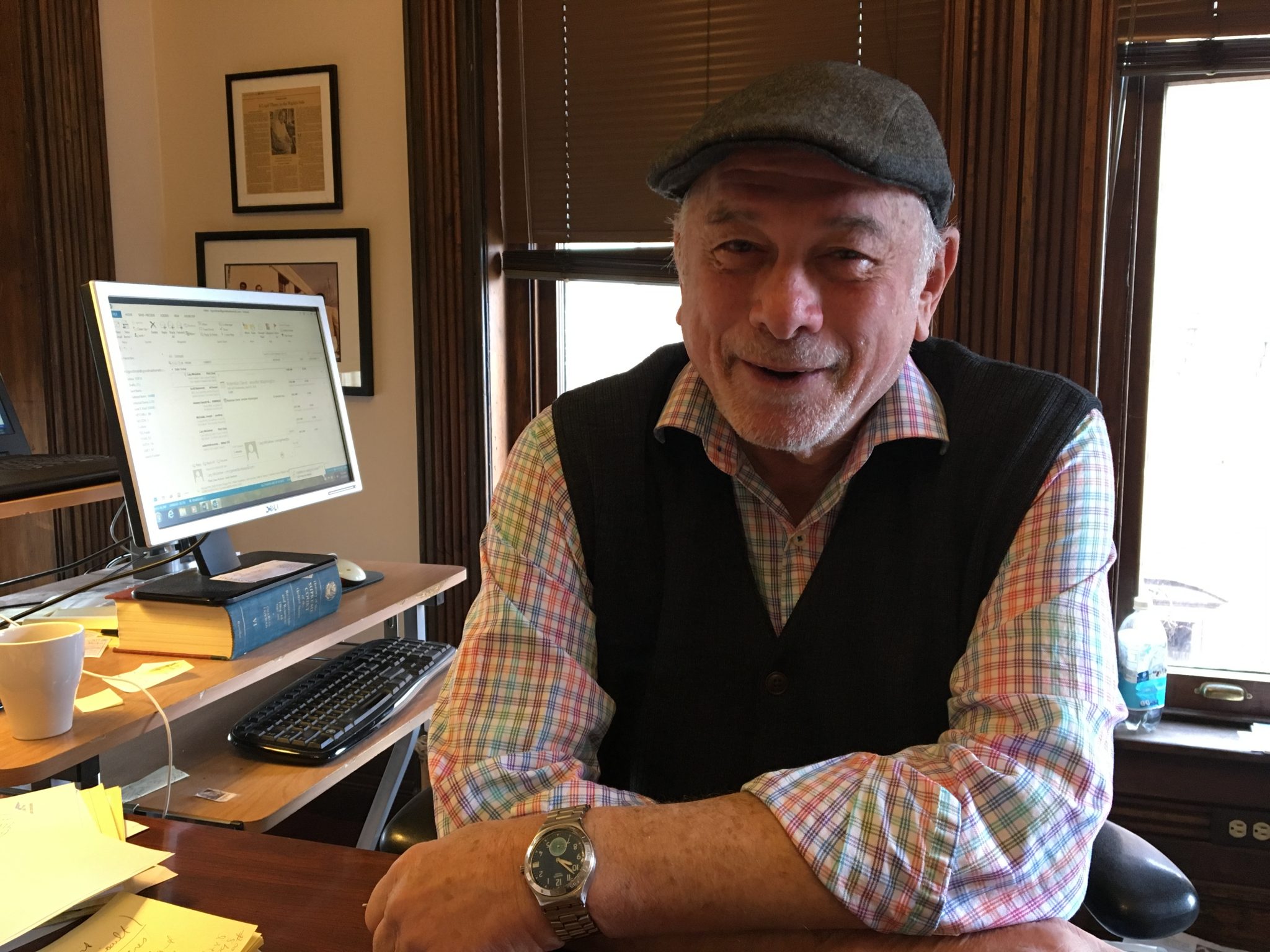

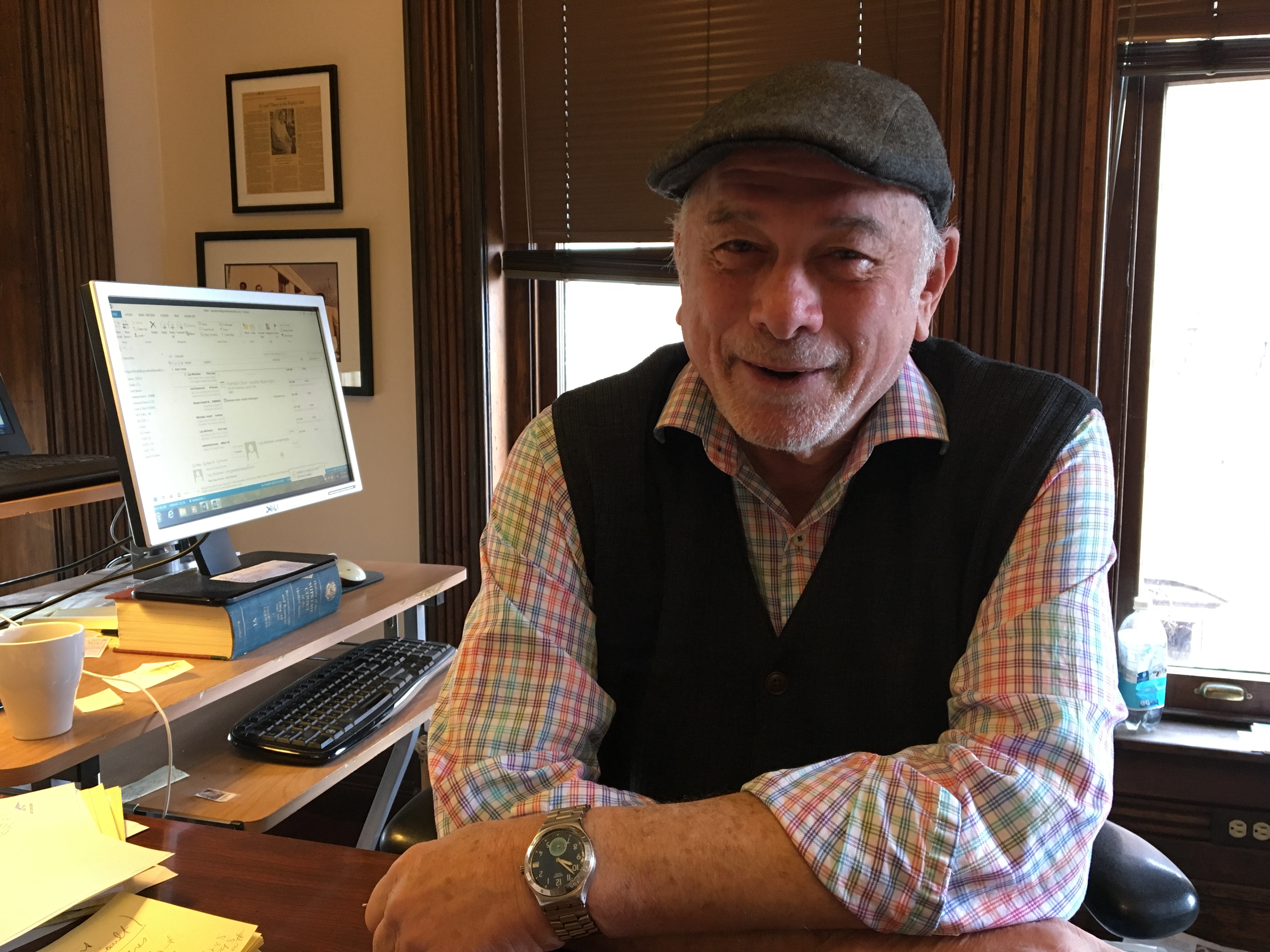

Headapohl, the newspaper’s managing editor, joined WDET’s Sandra Svoboda on Detroit Today to discuss her article and talk with Bill Goodman, one of the attorneys.

The links between Detroit’s African-American and Jewish communities are many, Headapohl says, not just linked by the violence of 1967 nor the attorney-client relationships. “As the Jewish community moved, the African-American community followed,” she says. “There was a close affinity.” Both groups also resided near the 12th and Clairmount, the intersection where the riot began.

Goodman, a Detroit-based civil rights attorney, remembers that evening. He had been visiting his parents in northwest Detroit and recognized the significance of what was happening as he drove toward downtown that evening. “You could see all sorts of people streaming out of storefronts and stores and all the rest of it, carrying things, police arresting people so it was obvious there were going to be massive numbers of detainees,” Goodman says.

The next day, he joined with other members of the National Lawyers Guild in Detroit Recorders Court. “We just waited for names to be called and people to be brought up in front of the various judges and were essentially volunteering to represent people,” Goodman says. “You could see people being brought in… People were held on Belle Isle … and on buses and held for days and days and weeks in some cases who were guilty of nothing more than a curfew violation.”

Goodman knew then what the Kerner Commission went on to find about one of the many causes of the rioting. “It was the result of police oppression of the African-American community in the city. I was less familiar with that before those events than I was after. It was clear, all one has to do is read the Kerner Commission report to know what it arose from: an all-white police force policing a large African-American community and a growing African-American community and doing so in a way that was blatantly discriminatory,”

The Detroit Journalism Cooperative is exploring the Commission’s findings this year in “The Intersection” project. Convened by President Lyndon B. Johnson following rebellions in several cities, the Commission concluded that a host of reasons – including all-white police forces who interacted inappropriately with African-American communities – led to the civil disturbances.

Goodman says the Commission’s conclusions have relevance to some of today’s police-community dynamics.

“Obviously there are great cops, wonderful cops and that’s how we know how to size up a bad cop. A cop who uses his power, his authority, and his ability to injure in kill in ways in which it should not. So being aware of that distinction and those difference has now come to the public’s attention,” Goodman says. “People can now see what misconduct really looks like.”

To hear the full conversation, click on the audio link above.