This Summer’s Algal Bloom in Lake Erie Was Large, But Could Have Been Worse

A wet spring was bad for farmers, but gave algae less phosphorus to feed on.

This year’s algal bloom in western Lake Erie was about as bad as scientists expected. But it could have been worse.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration predicted another significant mass of algae in the lake in 2019, fed mainly by farm fertilizers containing phosphorus. Rain washes the chemicals into streams, rivers and creeks that flow into the lake. Phosphorus promotes the growth of microcystis cyanobacteria, a blue-green form of algae.

The amount of phosphorus flowing into the lake this season was within NOAA’s forecast of how severe the 2019 bloom would be.

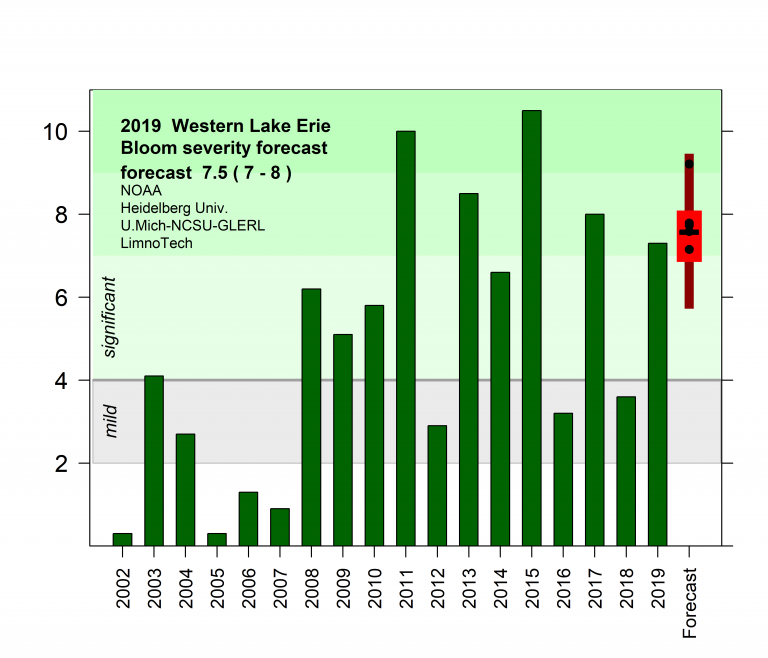

“We use a scale of zero to 10,” says NOAA researcher Rick Stumpf. “This year’s bloom was a 7.3.” That falls within the range of 7 to 8 Stumpf and his colleagues predicted in July. At its peak, Stumpf says the bloom covered about 700 square miles of the lake’s surface.

But if not for a wet spring that prevented many farmers from fertilizing their fields, Stumpf says this year’s algal bloom would have been a 10.

“It rained so much that many farmers couldn’t fertilize,” Stumpf says. “Some couldn’t even plant crops in their fields.”

Stumpf says as a result of the rain, the amount of phosphorus entering the lake was lower than expected. He says this proves an important point: Less phosphorus means smaller algal blooms.

“We know that if we can control the phosphorus, we can actually get the bloom sizes down from where they might be.” — NOAA researcher Rick Stumpf

Here’s another important point: Severity is not the same as toxicity, which is much harder to measure.

“We cannot directly detect toxicity,” Stumpf says. “And it changes through the season.”

Cyanobacteria create harmful toxins that can sicken people and pets, and contaminate public water systems. That’s what happened in Toledo in 2014. Stumpf says algal blooms can have long-term effects, such as depleting oxygen in the central part of the lake. A lack of oxygen can harm mayfly larvae, a major source of food for fish in Lake Erie.

Click on the player above to hear Rick Stumpf’s conversation with WDET’s Pat Batcheller, and read a transcript, edited for clarity, below.

Pat Batcheller, 101.9 WDET: How severe was this year’s harmful algal bloom in western Lake Erie?

Rick Stumpf, NOAA: We use a scale of 0 to 10. The 2011 bloom was a 10. This year’s was a 7.3, which makes it one of the more severe blooms. So it was worse than 2018 (3.6), but not as bad as 2017 (8.0).

Is severity the same as toxicity?

No. This is a measure of the biomass. We use satellite data to determine how much bloom there was over a 30-day peak. We cannot directly detect toxicity. These blooms typically are toxic, but that varies from year-to-year. You have to take field samples. We also measure the chlorophyll, because that’s a good measure of how much bloom there is and you have to compare them. It’s not an easy problem. And it changes through the season. The blooms are typically more toxic early in the season than they are later.

What harm, if any, did this year’s bloom cause to the lake, the plants, fish, other wildlife, and people?

It’s hard to determine. With a bloom like this, the first impact is economic. That includes the cost of treating water with activated charcoal, for example. It also impacts charter boat fishing and marinas. From an animal perspective, fortunately these blooms rarely cause fish kills. But the quantity of biomass can ultimately lead to low oxygen levels in the central part of the lake going into next summer, and that has larger ecosystem issues.

We know that phosphorus feeds algal blooms, and a major source of that is farm fertilizer that runs off into streams and other waterways that flow out to Lake Erie. Has there been enough progress in reducing the amount of phosphorus that gets into the lake, and if not, what needs to happen?

This year was a bit odd. We actually had a reduction in phosphorus, but it was not planned. It rained so much that many farmers couldn’t fertilize. Some couldn’t even plant crops in their fields. We had an interesting test of the question, “if we can manage the fertilizer better, will we have a reduction in phosphorus?” The answer is yes. I should add that, while we had a substantial bloom this time, if we’d had a typical phosphorus discharge, we’d have been looking at a severity of 10. So the good side is, we know that if we can control the phosphorus, we can actually get the bloom sizes down from where they might be. This was an incredibly wet spring. There’s an active effort going on, especially in Ohio, looking at testing soil for phosphorus, questioning whether they need to use phosphorus. I think we’ll see those changes over the next couple of years.

In what other ways does weather affect the bloom?

The bloom diminished very rapidly in September. We also saw that last year. In both cases, there were relatively strong winds all through the month of September. In past years, the blooms lasted well into September and even early October, with dense scums. People might remember in 2017, there was late scum on the Maumee River in Toledo. In 2011, there were huge scums off of Cleveland in early October. This year the bloom was mostly gone by the first week of October.

What long-term effects, if any, can harmful algal blooms have on Lake Erie?

One problem is low oxygen in the central basin. That can potentially affect mayfly larvae, which is the base of the food chain for a lot of fish. If that low-oxygen area expands, then there’s less growth area for fish. Another factor is overall health and safety. When you have thick scum, it’s gross. It’s also dangerous. Any scum is dangerous for swimmers as well as pets. You don’t want your dog to ingest any scum, because if they take in a lot, they could die from it. You’d have a situation where you can’t use this wonderful resource because the water is potentially dangerous, or you don’t want to use it because it’s not pleasant to be around. Those are long-term things we need to fix. The good thing is, it will turn around quickly. We’ve seen that repeatedly. If we have less phosphorus, we have smaller blooms. These things can be fixed if we get those levels down to where they were in the 1990s.