For Detroit Retirees, Bankruptcy Still Part of Daily Life

A year after Detroit’s bankruptcy case was resolved, some pensioners disagree on settlements, need for their cuts.

For City of Detroit retirees, the changes brought by bankruptcy are measured in the cuts they’ve taken to monthly pension checks and health care benefits. Nearly a year after the case’s resolution, some of them are recalling the bankruptcy proceedings and what the case has meant to their lives.

Shirley Lightsey, president of the Detroit Retired City Employees Association, had a seat at the negotiating table during the bankruptcy proceedings. As one of about 20,000 city retirees affected by Detroit’s bankruptcy, Lightsey worked for Detroit’s Water and Sewerage Department for three decades. She says, as an employee, she never doubted the security of the city’s pension system.

“You were told that you were going to have a pension. They had the formula for the pension, which had been improved over the years, and we expected to have our pension never to be diminished or impaired,”

But decades of Detroit’s fiscal instability threatened that guarantee. According to court records, the city owed more than $3 billion toward pension funding when it filed for bankruptcy, and that debt was part of the reason Detroit entered Chapter 9. According to the settlements reached in the case and outlined in the Plan of Adjustment, the city won’t make substantial contributions to its pension systems for almost a decade. When it does, those payments could be even lower.

For general service retirees, like Lightsey, the settlement translated to a 4.5 percent reduction in each monthly pension check. Cost-of-living allowances also were eliminated.

Detroit’s police and fire departments have a separate pension system. After the bankruptcy, terms for those pensioners are different than for other city workers. Nothing was cut from police and fire pension checks, and they retained 45 percent of their cost of living allowances.

But for both groups, reductions in health care benefits were staggering.

“The biggest hit personally, and to our members was the loss of health care. Police and fire don’t participate in social security so many of ours don’t qualify for Medicare,” says Don Taylor, president of the Retired Detroit Police and Firefighters Association. “Personally I worked side jobs so I did qualify for Medicare, but the additional cost that I assumed when the bankruptcy went into effect, I went from paying basically zero for healthcare premiums to roughly $950 a month.”

The city slashed its estimated $4.3 billion dollar obligation for healthcare and other benefits by 90 percent. But in doing so retirees were essentially left to fund their own health care plans.

Retired Detroit firefighter John Tucker says because of his other personal investments, he’s in a better position than some of his former co-workers. But he says he’s still feeling the impact of the cuts.

“After 36 years I thought my wife and myself would receive health care the rest of our life, and it’s gone now,” Tucker says. “Public employees historically work for less hourly pay because they have a promise for better benefits and better promise of better pension in retirement and now, like I say I was 10 years into retirement and all of the sudden the bankruptcy occurred, and we lost mainly we lost the healthcare benefit.”

Similar to when two of Detroit’s Big Three automakers reconfigured employee health care programs to save money, part of Detroit’s financial restructuring included the formation of new committees responsible for managing retiree health care benefits: Voluntary Employee Beneficiary Associations that operate as health care trusts for retirees, who have had to navigate another system for their benefits.

Lightsey says the fact that the Affordable Health Care Act was going into effect at the same time Detroit’s bankruptcy was taking away retiree benefits made the new systems even more complicated. “We have a very little amount of money for what we need and we are trying to be very conservative and give the retirees the best that we can and not change things too much for them because they’ve had enough uncertainty in the last two years,” Lightsey says.

During the proceedings as settlements were announced, city and state officials praised Lightsey for her work in helping reach deals with pensioners. Indeed a majority of pensioners who voted on the Plan of Adjustment last year did so in favor of the settlements.

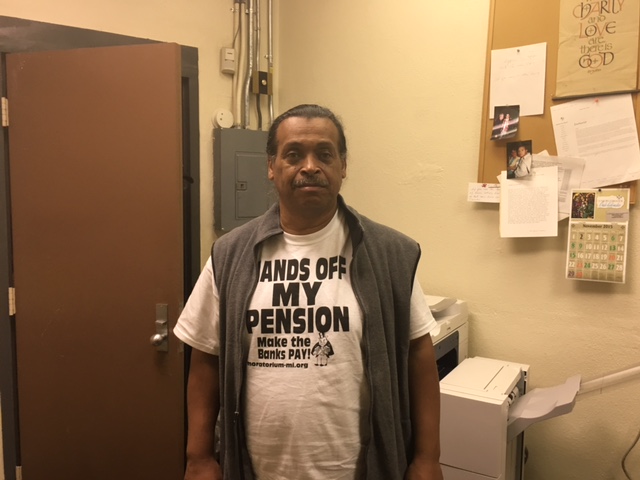

But some retirees remain critical of Lightsey and the settlement. Rudolph Markoe says his rights were not adequately represented during the bankruptcy proceedings. “The people who were supposed to be our advocates, at the end of the day, they all sold us out for whatever silver they got out of the deal. And you feel abandoned you feel lied to, you feel cheated,” he says.

Markoe is a member of another retiree group. It’s called the Detroit Active and Retired Employees Association.

“Principally we are a group that have been and continue to be concerned about the Detroit bankruptcy especially as it adversely affected our pensions,” says the group’s president, William Davis. “The whole thing was just wrong and as far as we’re concerned it was illegal.”

Davis says his group is continuing its fight in court. In September a federal judge in Detroit threw out the latest appeal challenging the city’s bankruptcy. Several other challenges have been unsuccessful. But Davis says he expected the rejection and is taking the case to the U.S. 6th Circuit Court of Appeals.

“Our constitutional rights were violated,” he says. “It’s just wrong on so many levels.”

One year after the city’s exit from the largest municipal bankruptcy in history, many Detroit retirees have moved on, trading feelings of indignant confusion for the bittersweet hope that their financial sacrifices will go toward creating a better and more stable city.But there are still some retirees who refuse to see the bankruptcy as a thing of the past.