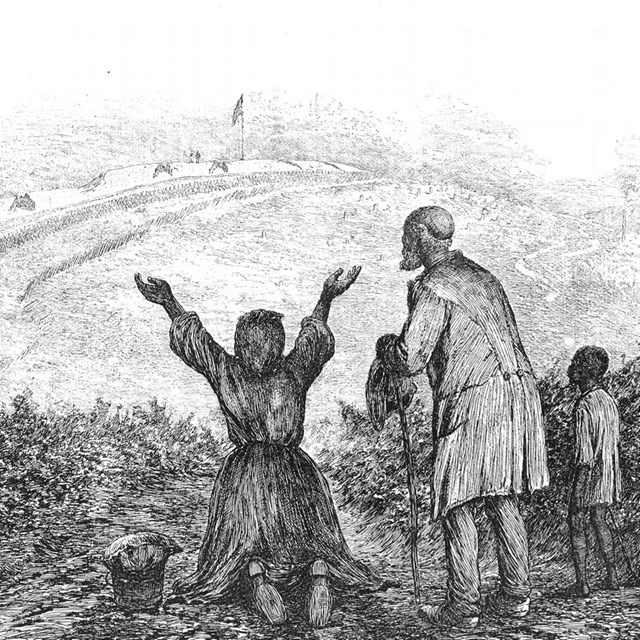

Have Immigration Crises Created a “New Underground Railroad” to Canada?

Maclean’s correspondent and experts draw parallels between slave crossings and undocumented immigrants.

President Trump continues to push for crackdowns on immigration. Meanwhile, our northern neighbor, Canada, sees increasingly more immigrants coming in.

They’re coming to America from various nations, then crossing the border into Canada. Immigrants’ journey to Canada is made possible partially by an underground network of drivers, advisers, and sometimes even smugglers.

This begs the question — in Trump’s America, are we seeing a new Underground Railroad?

That’s what Jason Markusoff, staff correspondent for Maclean’s, a Canadian national news magazine, outlines in a recent article titled, “The New Underground Railroad to Canada.”

He writes in the article:

The routes they take are impossibly dark, through scrub brush, mud, snow and water, fuelled by fear of getting caught and turned back south. But after fleeing from beatings and risk of death back home, and long journeys often of detention and other perilous pathways, the entry to Canada is just their last mile of hell.

Markusoff joins Detroit Today with Stephen Henderson to talk about his reporting and the parallels he draws with the Underground Railroad in his article.

“There are people who find out about these networks through social media,” he says. “The same way that in the 19th Century there were no rails, here it all takes different forms.”

Henderson also speaks with Rev. Dr. Lottie Jones-Hood, director of the Underground Railroad Living Museum at First Congregational Church, as well as Roy Finkenbine, a professor of history and director of the Black Abolitionist Archive at the University of Detroit Mercy. Finkenbine is also the chair of the Michigan Freedom Trail Commission.

“There’s a great deal of parallel there, and this is something that we want to equip people to deal with,” says Jones-Hood.

“It’s reminiscent of the language of the 1850s after the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850,” says Finkenbine, “where people of conscience, including people of faith, were saying there’s two sets of laws… there’s the law of the land — in this case the Fugitive Slave Act or, today, the immigration laws — there’s also the law of conscience or higher law. And people being willing to engage in civil disobedience then to hide, aid, protect, comfort people who were in violation of the law — runaway slaves or, today… undocumented immigrants.”

Click on the audio player above to hear the full conversation.