The Tradition of Tamales

For one Southwest Detroit business, tamales symbolize family, heritage and a way of life.

As thousands of Metro Detroiters prepare their holiday feasts, dinner tables in many homes wouldn’t be complete without tamales. The traditional Mexican dish consists of corn dough filled with pork or some other kind of meat or cheese, which is then wrapped in a corn husk and steamed. But as WDET’s Annamarie Sysling reports, tamales can represent much more than a delicious treat.

On a winding stretch of Vernor in Southwest Detroit, right next to the neighborhood’s famous geodesic dome house, sits Tamaleria Nuevo Leon. With its terracotta roof, red trim and curved archways, Nuevo Leon looks like a bit of Mexico dropped right in the middle of a snow-covered Midwestern city. With a little more than a week to go before Christmas, the shop’s owner Suzy Villarreal already has holiday preparations well underway. She says this is her busiest time of year. The Posadas begin on December 16, and things don’t slow down until after Christmas.

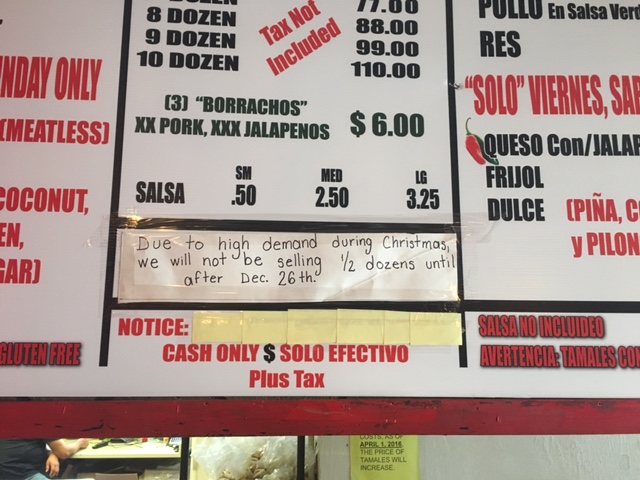

In the two weeks leading up to Christmas, Villarreal says Nuevo Leon sells around 80,000 tamales –that’s right– 80,000. The shop is equipped with 12 commercial chest freezers, most of which are filled to the brim with the traditional Mexican dish.

“Tamales at Christmastime is like turkey at Thanksgiving. You have to have tamales,” says Villarreal.

Even though the store sells a ton of their pre-made tamales, there’s also a demand for the corn dough tamale exterior, or masa, around this time of year. That’s because making tamales is as much of a tradition as the tamales themselves. “It used to be back in the other generations, back in my mom’s generations and my grandmother’s generation, it was mostly the women who made it and it was a day-long process,” Villarreal recalls. She says the meat –traditionally prok– is cooked in the morning. Then it’s time to grind the corn into a dough and add spices. The corn dough goes on the corn husk and then is filled with pork.

When all is said and done, it’s about a 16-hour-long process, and one that Villarreal knows well because she’s been doing it since childhood. It was her mother, Maria Villarreal, who started Nuevo Leon in 1957. “This is how I grew up. I was born in 1960, so this is all I knew. She would have us working as kids cleaning the corn shuck. At that time, the corn shuck doesn’t come how it comes now, a lot of little corn hairs sticking off your finger,” says Villarreal.

In addition to the corn husks, some other things have changed. Villarreal says it’s common now for the women, men and children to all participate in the cooking and preparation. Villarreal says she finds it “cool because it’s family time.” She adds that it’s a special opportunity for the younger generations to learn important traditions from grandparents. “The art is in the rolling,” says Villarreal. And, while many tamalerias have started to use machines to roll tamales, Villarreal still rolls hers by hand. It’s how her mother made them, using her hands as the primary tool, because she was fiercely dedicated to honoring Mexico’s culinary traditions and seeing this business succeed. Villarreal remembers her mother would regularly get phone calls after the shop closed, asking for two dozen of her handmade pork tamales. Villarreal says she gets those phone calls now, and always tries to make sure customers leave happy, and with tamales in hand.